Experienced diamond cutters and gemologists are improving their ability to identify certain lab-grown diamonds with loupes and microscopes. How have they been able to do this without advanced laboratory equipment? By learning to recognize distinctive inclusion types when they occur.

1. Metallic inclusions in HPHT-grown crystals

The HPHT process replicates the natural conditions under which diamonds formed below the earth’s surface from subduction. A carbon source, a diamond seed, and a metallic catalyst are put into a cell. That cell is placed into a massive mechanical press, where the contents are heated to near 1,400 C and subjected to staggering pressure. Upon reaching a certain temperature, the metallic catalyst begins to melt, dissolving the carbon, and the enormous pressure causes precipitation to the diamond seed, growing a larger diamond.

The use of that metallic catalyst permits growth to occur at lower temperatures, but a frequent result of the HPHT growth process is metallic remnants, which remain trapped inside the crystal. These remnants often have a man-made appearance when seen under magnification, and they are frequently reflective—unlike any naturally occurring inclusion type.

2. Planar inclusions in CVD-grown crystals

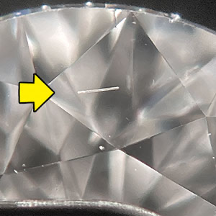

The CVD process does not grow crystals in the same way that natural diamonds grow. Instead, hydrocarbon gas is superheated in a vacuum chamber to between 800 and 1,000 C. At that point, carbon atoms begin to separate from their molecular bonds. The released atoms descend and land on a flat wafer of previously grown HPHT synthetic diamond substrate, growing the crystal vertically in parallel layers. Depending on equipment quality, cleanliness, and production goals, crystal growth can undergo a series of stops and starts during the process.

A byproduct of vertical growth is the possibility of characteristics that become grouped together on a single linear plane within the finished crystal. Such structured planar inclusion groups rarely or never occur in natural gemstones.

3. Quality control

Over the past several years, the rising visibility and popularity of lab-grown diamonds have created a “lab-grown diamond rush.” As more and more growers enter the arena, lab-grown rough output has taken on more variability. This variability can be exaggerated by entities entering the field with less capital resources, lower quality equipment, presses converted from industrial to gem-quality use, contamination confounders, etc. Turnaround choices also play a role. When a growth process is pushed to maximum speed it will increase the grower’s output, but it will also increase the likelihood of inclusion types that experienced gemologists can identify as distinctive to lab-grown diamonds.