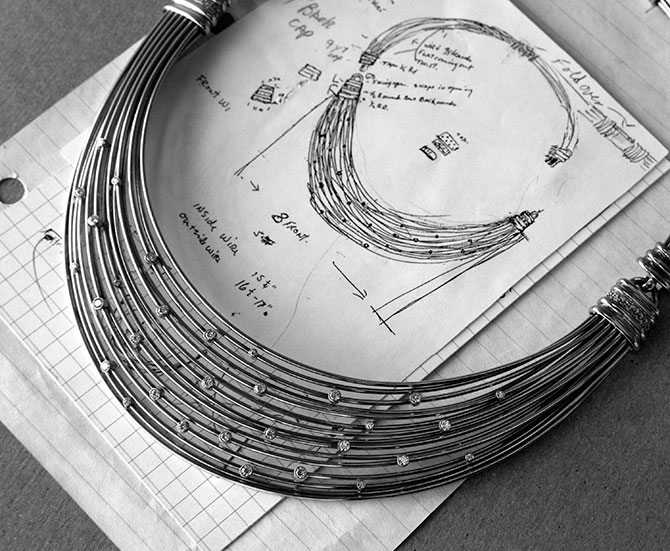

In the early 1980s, only a handful of years after establishing his first jewelry brand, Flaircraft, Jose Hess made the decision to start stamping his own name on the backs of his designs.

The switch had been a long time coming, recalls the German-born designer, whose family fled to Colombia to escape the Nazis. “I had wanted to call my company ‘Jose Hess’ from the beginning, but when I mentioned it to people in the industry, they would say, ‘Who’s going to buy jewelry from someone named Jose? Nobody’s heard of you, and nobody’s going to buy it.’ ”

In the late 1970s, when Hess was starting out, “Americans were not well-known for making jewelry,” he says. “So retailers often said their jewelry was made in their shop, or that it came from Italy or Paris. That was the spiel then. There were almost no designers selling by their own name.”

But Hess, whose first job in the United States after emigrating from Colombia was in David Webb’s atelier, had no desire to toil at the bench in obscurity his entire career. When he changed his company name from Flaircraft to Jose Hess, he even made little plaques embossed with his logo that he asked jewelers to put in their windows—a radical request at the time.

Though he didn’t know it then, the designer—along with contemporaries Penny Preville, David Yurman, Esther Gallant, and Beth Moskowitz—would pioneer a movement that recast the role of jewelry designer, both in and out of the trade, as a career with far-reaching financial, social, and cultural opportunities. That shifting of the sand brought seismic change to the way jewelry was bought and sold.

There had been superstar American jewelry designers before, of course. Paul Flato designed dazzling jewels for film stars including Rita Hayworth, Joan Crawford, Marlene Dietrich, and Katharine Hepburn in the 1930s; Duke Fulco di Verdura’s Fifth Avenue atelier in Manhattan was a hot spot for socialites and movie stars in the 1940s; and Webb, a North Carolina native, made his name bejeweling the likes of Elizabeth Taylor and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis in pieces now considered midcentury icons.

But for every Flato and Verdura there were hundreds of U.S. manufacturers creating generic engagement and fashion jewelry that made up the bulk of jewelers’ inventory in the ’60s and ’70s.

Additionally, the independent designers lugging their rings, brooches, and lariats into boutiques during the disco era were a different breed. They were, with exceptions, fine artists who chose jewelry as their medium—and crafted their creations for style lovers, not state dinners. Hence, their collections often competed directly with the generically manufactured pieces that filled nearly every jewelry case in the country.

Many of Yurman’s first offerings resembled free-form sculptures, while Preville’s designs were cool and casual. “I wanted to make jewelry that I wanted to wear daily in my own life,” she says. “I was a mother and young when I started out, and I wanted to wear what I made.”

Preville also remembers countless rejections when presenting her eponymous line to shop owners in the early days: “Retailers were very reluctant to sell a [branded] collection,” she says. “They were wondering why they should support me. They wanted to support themselves! I had brochures and signage, and I think some retailers didn’t understand that at all.”

But soon, the tide would turn. By 1976, Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone editors were regularly reporting on designers including Hess, Preville, Moskowitz, Marsha Breslow, Alyce Simon, and Gayle Saunders—names that crept in among the enduring manufacturer labels (Av-Dor and High-O Silver & Gold Co., for example) that had dominated the magazine’s pages for decades.

The magazine’s editors were also suddenly penning profiles on small indie brands such as “sculpture to wear” jewelry designers Rachel and Eli Gera and legendary Robert Lee Morris, referring to makers specializing in interesting and artistic designs.

“Along with artists, sculptors, poets, and composers, struggling jewelry designers also dot the lofts and garrets of New York,” reported New York editor Ettagale Lauré (who now goes by Ettagale Blauer) in the September 1976 issue of JCK. “Like their fellow artists, they have visions, frontiers they intend to explore and a longing to achieve recognition.… A few prove proficient enough as artisans to at least survive. They are the ones who studied their crafts first.”

But they didn’t just survive. Many went on to build successful and enduring businesses, racking up prestigious industry awards along the way. Their success had a softening effect on retailers, notes Preville, who won the Retail Jewelers of America (RJA) show’s designer of the year award in 1978. In 1980, David Yurman was named designer of the year by the Cultured Pearl Associations of America and Japan, the same year he received his first prominent inclusion in the pages of Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone.

If the pages of the magazine are to serve as a guide, women jewelry designers were the pioneers of the late-1970s indie jewelry scene. An article by Annalee Gold in the August 1978 issue called out the “Hot Designers for ’79,” and all four were women: Gallant, Moskowitz, Enid Kaplan, and Just Theo (a designer who went by Theo—no last name).

In the magazine’s January 1980 issue, in an article titled “The Dawn of Designer-Name Jewelry?” Lauré questioned the logic of the industry’s masking—even hiding—its design innovators. “Fine jewelry has an anonymity about it that is virtually unique. Why, in fact, is there no nationally known line of fine jewelry with a designer name? There has been, and still is, designer name jewelry—but it’s all costume,” Lauré wrote, name-checking designers such as Kenneth Jay Lane and Christian Dior. “It would seem natural to extend the same process to fine jewelry.”

She also chronicled retailers’ reluctance to carry branded lines: “There is little question at this point that designer names will make inroads into the jewelry industry. But the big question is, ‘Will retail jewelers be a part of it?’ The answer seems to be—not if they can help it. Kicking and screaming, some retailers may be pulled into carrying the merchandise.” Several retailers quoted railed against the idea. Said one: “We are not crazy about selling someone else’s name.”

Of course, not all retailers resisted. And in a few cases in the late ’70s and early ’80s, it was forward-thinking jewelry sellers who propelled independent designers forward.

Yurman, arguably the most successful American jewelry designer then and now, found an early champion in Marie Helene Morrow, CEO of Reinhold Jewelers in Puerto Rico. Morrow, who’s nurtured scores of emerging jewelry designers in her long career, met the then-unknown artist in the early 1980s, when she was walking the aisles of the RJA show in New York City.

She carried and promoted the David Yurman brand early and avidly, though at least once she had to talk the designer out of quitting the business altogether. “A few years after we met, David calls me on the phone and says, ‘I’m going out of business. This is too much for me,’ ” she recalls. “I said, ‘I’m hanging up and I’m taking the next plane to see you.’ And that’s what I did. I got to New York, and he was in this tiny little office and he had all his jewelry in front of him and said, ‘I’m giving you first opportunity to take what you want.’ I said, ‘Are you insane? You’re the best there is!’ ”

Morrow took the jewelry back to Reinhold and “sold every piece for double or triple the mediocre prices he was asking,” she remembers.

Hess also had moments of doubt in his brand’s rocky early years—but the designer powered through by bypassing retailers and building his following directly—investing big-time in print advertising. Hess ran full-page ads in trades such as Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone, but also in Town & Country and consumer magazines that targeted affluent shoppers. The investment paid off. Jewelry fans loved the designer’s chic, occasionally trippy-feeling ads and asked their local jeweler where they could buy his pieces. (Then, as today, consumers wielded power.)

In the January 1980 issue of JCK, retailer Bob Couch of Couch’s Jewelers in Anniston, Ala., astutely grasped that the decision to carry designer collections would be made by the consumer, not the retailer. “People walk into the store and ask for Peter Lindeman or Jose Hess,” he told Lauré. “I think they saw it in a magazine. They know what they want, and it’s up to you to come up with the goods.”

For Hess, breaking into the business as himself, unveiled and out front, “wasn’t easy, and was a very slow process,” he says. But the undeniable brilliance of his—and others’—work ultimately cut a clear path to acceptance and success for the innovative designers who would follow. “Little by little, it became something very powerful.”

Top: David Yurman Renaissance cable bracelet in sterling silver and gold with tourmalines and smoky quartz, 2004