Walk the floor of any jewelry trade show and it’s clear: Our industry is sustained by important contributions from key countries and ethnic groups, from the diamond cutters of Mumbai to the manufacturers of Hong Kong. How did we get so global? It didn’t happen overnight.

The American jewelry trade has always relied on an international supply chain to connect its operatives with gemstone sources from around the globe. But when the country’s first diamantaires, most of them European Jews who began arriving in the United States in the 1840s, set up offices on New York City’s Maiden Lane and, later, on the Bowery before landing at their current location on 47th Street, the industry was overwhelmingly local.

“You didn’t know much about what was going on in the rest of the world, other than having the European connections to import diamonds and gems,” says diamond industry analyst Ben Janowski, founder of Janos Consultants.

The industry mindset began to change in the 1970s, however, for a few reasons, including the introduction of India as a new center for diamond cutting and Hong Kong as a new hub for jewelry manufacturing (more on this later).

It was also during this decade that the United States dropped its import tariffs on diamonds, “which opened the door for Belgian, Indian, and Israeli dealers to start selling directly to U.S. manufacturers and retailers,” Janowski says.

By the mid-1980s, the American jewelry industry was a global landscape with touchpoints across several continents. It even prompted a JCK article in June 1985 advising “American businessmen” on how best to communicate with their “overseas counterparts,” including priceless tips such as “Don’t use colloquial turns of phrase like this is a whole new ballgame or let’s talk turkey.”

International trade shows were promoted and covered frequently in our pages at that time, providing jewelers with a more organized, and scheduled, way to find what they needed and from whom, whether buyers were in the market for Swiss watches, piles of gold chains from Italy, or parcels of pink sapphires from a supplier in Bangkok.

Today the pipeline is even shorter, and the players’ backgrounds are more diverse—and more interconnected—than ever. How did this happen?

The definitive answer could fill a Ph.D. dissertation. But after combing 150 years’ worth of our archives and other media for insights, interviewing respected industry analysts, and seeking perspectives from a number of jewelry businesses whose ownership spans multiple generations, we’ve identified five sociohistorical forces that had the greatest influence on the globalization of the American jewelry industry.

Travel Improvements

Early issues of our magazine consistently made note of “trans-Atlantic voyagers”—the jewelers and importers headed to Europe via steamer ship to buy loose stones from Sri Lankan and Thai suppliers in Paris, or to various Italian cities for finished gold jewelry. After World War II, travel by plane was a more common occurrence, thus making buying trips easier and faster.

For example, in the 1950s and 1960s, a trip to the Sri Lankan capital of Colombo required roughly four days’ travel time from New York City; today, the same trip takes less than a day. And vice versa: “People from all over the world walk into our offices peddling stones, and it makes business fun and interesting,” says Tom Heyman of Manhattan-based heritage jewelry brand Oscar Heyman. (See “Once Upon a Time in America.”)

Mass Production

The traditional diamond pipeline began to transform in the early 1970s. For decades, diamonds had entered the American marketplace through a clear-cut channel: Select De Beers sightholders claimed their allotted parcels of rough from what was then known as “The Syndicate” and cut the stones before selling the goods to New York City–based dealers, who in turn sold them to wholesalers and, finally, retailers. The creation of America’s interstate highway system was the unlikely catalyst for a shift in the supply chain: It led to the expansion of shopping centers, which in turn prompted the rapid-fire growth of large mall jewelry chains targeting consumers at the middle to the low end of the market.

In 1972, an article in Newsweek connected this phenomenon with the decline of the old-guard jewelry businesses that relied on family and community connections. “As people get old and die, we are not able to replace them,” a member of the Diamond Trade Association told the magazine. “In general, their sons who go to college do not want this kind of business. The flood of immigrants has dried up, and the old families are disappearing.” And the wave of the future, said reporter Jane Friedman, “is represented by the impersonal image of the Zale Corp.”

And this turned out to be true, at least until the 1990s. When the mall retail format reigned supreme, chains like Zales began to meet customer demand for small diamonds (for engagement rings) and aggressively priced finished jewelry (such as tennis bracelets) easily—and cheaply—through a network of suppliers in India, Hong Kong, and mainland China. But the consequences of mass-producing jewelry and global sourcing were far-reaching.

Mass merchandising “brought vigorous price competition into what was once a high-profit, slow-turnover business dominated by specialty retail jewelers,” says Russell Shor, senior industry analyst at GIA. “This forced the contraction of the supply chain and eliminated most of the large [domestic] wholesaling companies and secondary diamond sellers which had dominated the mid-pipeline until then.”

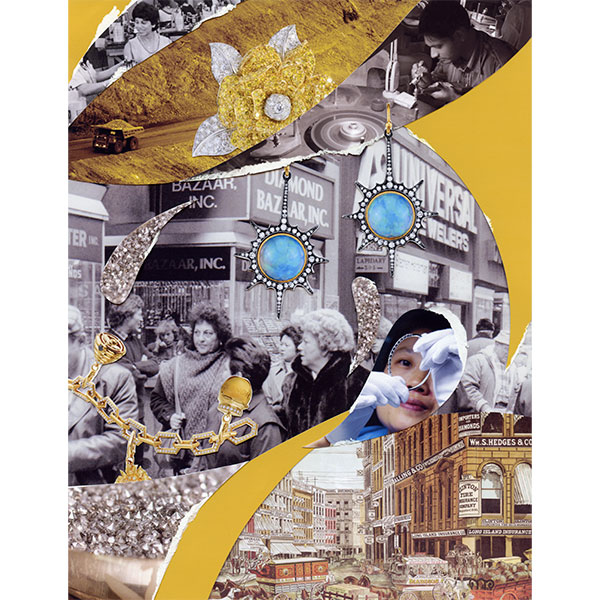

1. Melting silver trees in a factory in Guangzhou in China’s Guangdong province; 2. Maiden Lane, the lower Manhattan street where the jewelry industry once converged, in the late 1800s; 3. Diamond cutting in Ramat Gan, near Tel Aviv, in 1975; 4. Indian diamond cutters in Surat; 5. 47th Street, the heart of New York’s Diamond District; 6. Rough diamonds from the Argyle diamond mine; 7. The retail hub 575 Fifth Avenue in the Diamond District; 8. An aerial view of Hong Kong in 1970; 9. Workers setting stones into silver in Guangzhou’s Panyu district

Volatile Gold Prices

Elder statespeople recall wistfully when gold cost $35 per ounce, a period that lasted roughly from the 1930s to the early 1970s, when the stability of the U.S. economy began to waver. Metal prices continued to rise well into the 1980s, in step with that decade’s reputation for being a time of freewheeling wealth and excess. The price increases have persisted in recent decades (see “Gold Standard”).

“It’s ripped through the business,” Janowski says. “Mountings are the single most important component of jewelry-making, and when gold prices pushed the metal out of popular price ranges, it ripped out the core ability of retailers to produce a product that people could afford.”

In response, the industry saw an opportunity to mitigate its losses: “In the early 1980s, some U.S. jewelry manufacturers began outsourcing to China,” Shor says. “Before the country’s economic reforms, however, doing business there was difficult. It was difficult to import diamonds and precious stones. All that changed when China liberalized its currency and importing procedures, and its economy improved.”

Rio Tinto’s Argyle Mine

Like China, India became a low-cost outsourcing destination for American jewelry companies. But the country’s most enduring, and palpable, contribution to our industry is diamond cutting.

In June 1985, JCK ran an in-depth, on-the-scene article about India’s diamond-cutting centers that opened with this: “The Indian diamond trade likes to say it did for diamonds what Henry Ford did for cars: It made them affordable to the American middle class.”

When Australia’s Argyle diamond mine opened in 1985, India was able to corner the market on “low-quality smalls”—stones that wouldn’t be cost-efficient to cut in places like Belgium and Israel. There, such work was entrusted to master craftsmen who commanded a much higher salary than the teenagers who flocked to Surat, India’s diamond manufacturing hub, to learn a trade and earn a living—“like prospectors to the Klondike gold fields,” according to our article.

Argyle was a game changer. The stones that streamed from the mine—small ones, with marginal color grades (including some browns that came to be christened champagnes and cognacs)—offered unprecedented growth opportunities for the already-thriving Indian diamond trade. The Argyle rough was sent to India for processing, creating more jobs, which meant building more sophisticated factories and making room for new wholesale businesses.

Meanwhile, established Indian diamond industry leaders—who now had the funds, street cred, and connections to explore the higher-end sectors of the marketplace—began to sell downstream (i.e., directly to retailers).

“Since the new millennium, probably in excess of 80% of stones are passing through Indian hands,” says Janowski.

Veteran retailer Esther Fortunoff, who has always sourced stones and jewelry from around the world, credits the Indian cutters for having the greatest influence on the industry’s globalization. “Suddenly the industry had access to thousands and thousands of carats of diamonds that could be made into jewelry—a lot of it affordable,” she says.

The Internet

So much of our work now happens online that you may have forgotten how disruptive the internet was when usage became more mainstream around the turn of the millennium. Not only did the World Wide Web change the way consumers shop for jewelry, but it also made business-to-business transactions more expedient.

These days the geographical distance between all points of contact has all but evaporated: A gem supplier can place orders directly with a mine in Brazil via WhatsApp. An American public relations firm can alert domestic and international media to breaking news on behalf of a Japanese client. A gallery can commission a custom piece from a Germany-based artist within hours of receiving an inquiry.

Social networks also connect the industry on a global scale and have become vital platforms for moving product, whether you deal in gemstones, sell estate jewelry, or want to tell your followers where to find you at JCK Las Vegas or VicenzaOro. They also serve as vehicles for forming and nurturing friendships, sharing resources, and seeking colleague-to-colleague advice.

As the pipeline between jewelry players has narrowed, the jewelry field itself has grown larger and more diverse. The boundaries are blurrier, but the possibilities are endless.

Illustration by Maxwell Burnstein

Jewelry in illustration: Gold and platinum yellow diamond gardenia brooch, $94,000, oscarheyman.com; 22k gold and oxidized sterling silver opal earrings with diamonds, price on request, armansarkisyan.com; B collection 5-charm bracelet in 18k yellow gold, $24,000, gumuchian.com

(Illustration photos, from top: Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy; Erin Jonasson/Fairfax Media/Getty; David Gee 4/Alamy; Alan Raia/Newsday Rm/Getty; Lucas Schifres/Getty; Hum Historical/Alamy/Hum Historical/Alamy)

(Inset photos: 1 & 9: Lucas Schifres/Getty; 2: Museum of the City of New York/Art Resource; 3: Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy; 4: David Gee 4/Alamy; 5: Richard B. Levine/Newscom; 6: © 2018 Rio Tinto; 7: Shannon Stapleton/Reuters/Newscom; 8: Bettmann/Getty)