As retailers and designers gravitate toward their variety and accessibility, so-called semiprecious stones have moved from supporting players to starring roles

For centuries, conventional wisdom when it came to the pecking order of jewels put diamonds and the “Big Three”—ruby, sapphire, and emerald—at the uncontested top of the heap. The remaining multitudes fell into the vast semiprecious category: lovely, to be sure, but rarely the stuff of heirlooms or the most enduring designs.

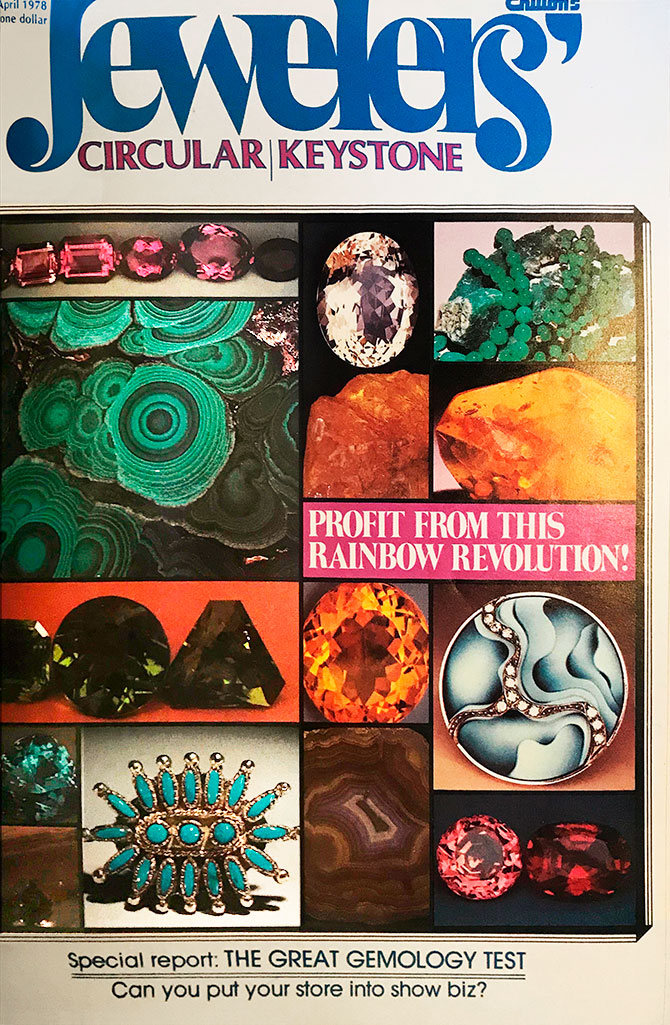

Generations of JCK issues show a more nuanced picture, with semiprecious stones seesawing between flashes of popularity and playing second fiddle to traditional materials.

In February 1914, columnist Isabella M. Archer identified a “notable tendency at present to discard all colored gems as well as pearls in the most sumptuous jewels.” But only five years later, in March 1919, amethyst became de rigueur because it was “the recognized post-war color.”

At midcentury, according to the April 1956 issue of Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone, selling diamonds was “the only true definition of a jeweler.” But not two decades later, during the psychedelic Age of Aquarius, semiprecious stones were the centerpiece of the “colored stone ring thing” that was a standout trend in 1969.

In the recessionary ’70s, gem sales slumped across the board, we said in December 1976, with semiprecious stones seeing “even worse” results than their pricier precious counterparts.

Since the early aughts, however, the momentum for these gems has grown apace. Today, stones that consumers hardly recognized a decade ago are hurtling toward sustained sought-after status. Exhibit A: the run on engagement rings in millennial-pink morganite.

What accounts for the snowballing popularity of sphenes and spinels, chrysocolla and kyanite? Stuart Robertson, vice president of Gemworld International, points to the spiraling cost of rubies, sapphires, and emeralds.

As a result, semiprecious stones—especially those that look like more highfalutin gems—are hot commodities. The strength of red garnets and tourmalines has a lot to do with finding something that resembles ruby but is more affordable, Robertson says.

Fledgling brands seeking distinction (and affordability) often gravitate to semiprecious stones, which “are available in the sizes and shapes that designers want,” says Doug Hucker, CEO of the American Gem Trade Association. “And most of them are repeatable. You can get big looks for less money.”

If AGTA has its way, the term semiprecious will soon fall out of favor. The organization’s code of ethics recommends AGTA members avoid using it to describe gems “because it makes a stone sound semi-desirable,” Hucker explains. We wholeheartedly agree.

Top: Butterfly pendant with clear fire opals, paraiba, and diamonds in 18k white gold; $198,000; victorvelyan.com