Since the mid-20th century, selling diamond rings to brides has formed the backbone of the jewelry business—and JCK has counseled retailers every step of the way

The ancient Egyptians were the first to use a ring as part of the marriage ceremony or contract. In Egyptian hieroglyphics, a circle or circular mark is used to denote or represent Eternity. From that fact has been developed the thought or idea that the wedding ring…because it is circular in shape and hence has no beginning or end…symbolizes the lasting quality of the love that has prompted man and woman to seek unity in the bonds of wedlock.”

So wrote William Scheibel in the August 1957 issue of Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone.

We have lived with this custom for so long, it’s almost shocking to learn that before World War II, the bridal business looked nothing like it does today. Although statistics vary widely, some estimates say only 10% of betrothed women received a diamond engagement ring in 1939.

It’s a far cry from today’s bridal-centric retail jewelry market, in which upwards of three-quarters of U.S. couples get married with an engagement ring. To say nothing of what they spend: $6,351 on average, according to The Knot’s 2017 Jewelry & Engagement Study.

To commemorate JCK’s 150th year, we stepped back in time to review the bridal category over the decades: how it’s evolved, which products have gone in and out of style, and what things haven’t changed.

A bride graced the cover of The Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone in 1936, but the articles inside focused on silverware and gifts rather than diamond engagement and wedding rings. “Whenever possible, the store makes contact through a mutual friend and inquiring whether or not the couple have made plans for their silver,” we wrote.

The years that followed were punctuated by the Great Depression and a world war. Weddings declined—as did jewelry extravagances—as consumers struggled to pay for necessities such as food and housing.

Immediately following WWII, however, the bridal business bounced back in a big way: 1946 saw a high of 2,307,747 weddings, according to the National Office of Vital Statistics. A 1947 marriage poll in the magazine found that jewelry sales attributable to marriages accounted for 43% of the business; engagement rings accounted for one-third of all band sales (excluding wedding bands); a wedding ring for the groom was bought in at least one of three instances (indicating the double-ring ceremony was gaining traction); the price range for engagement rings was between $100 and $199; and yellow gold was the most popular metal.

There’s no denying the role De Beers played in the boom. In 1947, N.W. Ayer & Son copywriter Mary Frances Gerety came up with the phrase A diamond is forever and the bridal category hasn’t been the same since.

By the early 1950s, amid the Korean War, marriage was on the rise again. “Once again the sound of marching feet of men in uniform echoes in the increasing numbers of couples walking down the middle aisle to the altar,” The Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone wrote in May 1951.

For independent jewelers, engagement and wedding rings were an important profit center, but so were silverware, dinnerware, and glassware of which “the coordinated merchandising should be a regular aim of the store,” we stated in June 1952.

It didn’t take long for diamond engagement rings to dominate the category. In November of that year, the magazine reported that “diamonds are still a jeweler’s best friend.” Diamonds represented 23% of jewelers’ annual volume and a still higher percentage of profits. And diamond engagement rings produced as much revenue for the average retailer as all other diamond sales combined.

It didn’t take long for diamond engagement rings to dominate the category. In November of that year, the magazine reported that “diamonds are still a jeweler’s best friend.” Diamonds represented 23% of jewelers’ annual volume and a still higher percentage of profits. And diamond engagement rings produced as much revenue for the average retailer as all other diamond sales combined.

Also by this time, 75% of jewelers were targeting yesterday’s brides—those who did not have the resources to buy engagement or wedding rings when they got married, but might now—as an important market. The average diamond engagement ring in the early ’50s at this time was $167.

The magazine seized the momentum. “Encourage every engaged girl to have a diamond immediately on betrothal,” wrote advertising expert Dorothy Dignam in the April 1956 issue of Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone, in an article rife with images of diamond rings in emerald, marquise, heart, and brilliant cuts. “Sell the wedding band as a separate ring.… Today’s engaged girls are often teenagers, who think they know it all. Usually, they don’t know what ‘solitaire’ means! Explain things gently, be friendly, but help them make up their minds.”

The magazine seized the momentum. “Encourage every engaged girl to have a diamond immediately on betrothal,” wrote advertising expert Dorothy Dignam in the April 1956 issue of Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone, in an article rife with images of diamond rings in emerald, marquise, heart, and brilliant cuts. “Sell the wedding band as a separate ring.… Today’s engaged girls are often teenagers, who think they know it all. Usually, they don’t know what ‘solitaire’ means! Explain things gently, be friendly, but help them make up their minds.”

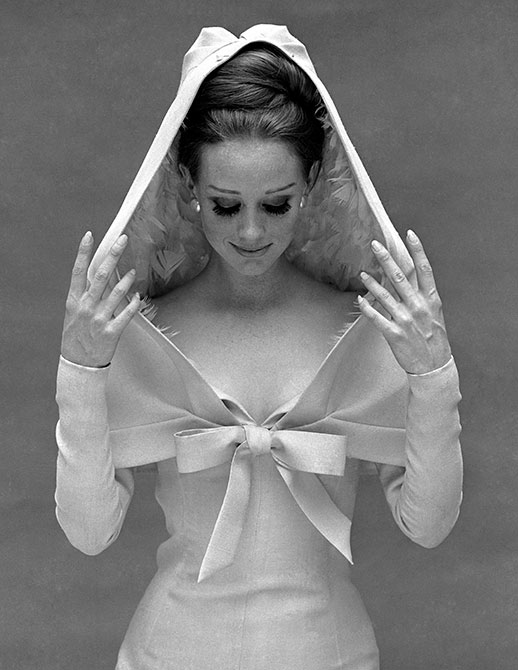

At the outset of the 1960s, a rising middle class with greater discretionary income boosted the prospects for bridal sales. “Is your store ready for the wedding march?” we asked readers in March 1959. By this time, 80% of brides received diamond engagement rings. Not only that, stones were getting progressively bigger.

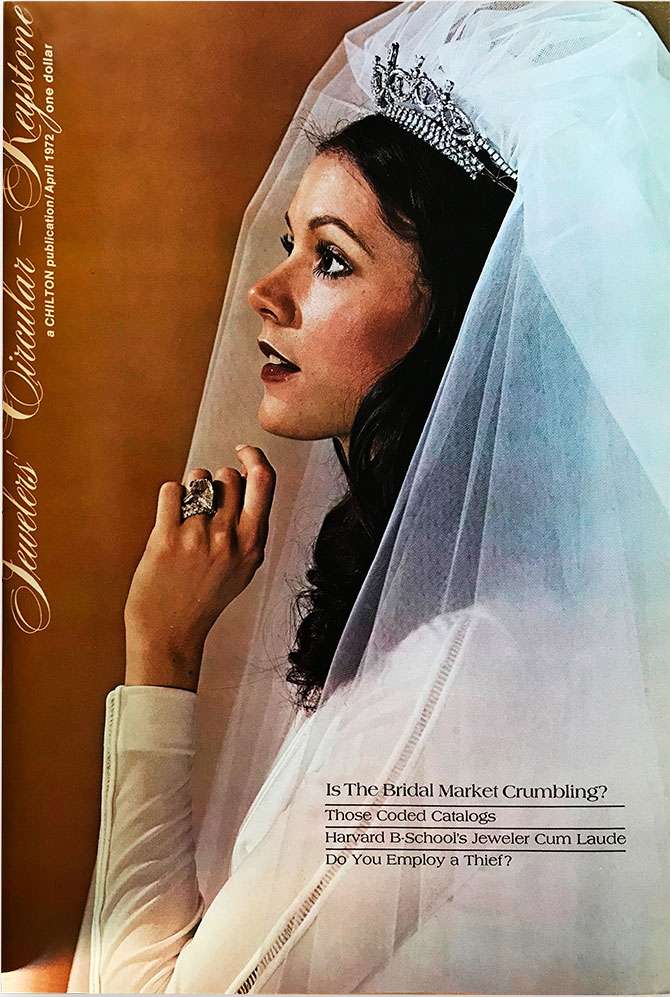

A decade later, however, the energy crisis, inflation, and the rise of antiestablishment thinking all created uncertainty in the bridal arena. In an April 1972 article titled “Is the Bridal Market Crumbling?” editor Ettagale Blauer questioned the future of nuptials: “Marriage contracts read like preliminary skirmishes for divorce actions, weddings take place in meadows, out of airplanes—everywhere, it seems, but at the altar.”

A decade later, however, the energy crisis, inflation, and the rise of antiestablishment thinking all created uncertainty in the bridal arena. In an April 1972 article titled “Is the Bridal Market Crumbling?” editor Ettagale Blauer questioned the future of nuptials: “Marriage contracts read like preliminary skirmishes for divorce actions, weddings take place in meadows, out of airplanes—everywhere, it seems, but at the altar.”

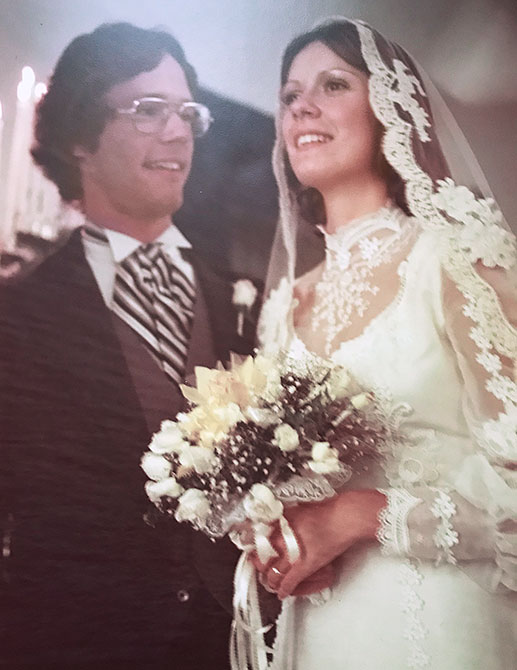

That’s what the noisy headlines said, at least. Most girls were still getting married with traditional pomp—and diamonds! A December 1977 editorial cheerfully reminded jewelers that “even hippies like fine things.”

The dawn of the 1980s brought with it a societal shift: A July 1980 article advised jewelers to boost engagement ring sales by going after the remarriage market. (In 1979, one in three marriages was second time around.) Three years later, however, we heralded the return of the traditional bride and wedding. By the end of the decade, 24.8 million marriages had been recorded, more than in any other decade in history.

September 1988 marked the first time platinum warranted its own feature story in the magazine. “It’s the most precious metal in the world—and the most difficult to work with,” wrote Cindy Edelstein. (Within a decade, the white metal would rule the high end of the bridal sector. In JCK’s March 2001 issue, Platinum Guild International touted that at least a quarter of all couples chose platinum for their bands.)

sylviecollection.com

The 1990s saw the magazine embrace a progressive mindset. Two decades before gay and lesbian marriage was legalized in many states, jewelers recognized an opportunity to appeal to same-sex buyers. “You can’t afford to be blinded about who loves whom in today’s world,” wrote Charlotte Preston in JCK’s June 1996 issue.

Two years later, in September 1998, the magazine heralded yet another game changer: the internet. Although online jewelry sales were relatively small at the time, the category would soon see its sales double year over year. (Blue Nile, the Seattle-based pure-play diamond website, was one of the first to turn a profit in the fourth quarter of 2001.)

Around the same time jewelers began to take the World Wide Web seriously, they also noted the emergence of a powerful new demographic known as Generation Y, aka millennials, a group of young people 72 million strong and defined by “the Internet, digital technology, and domestic terrorism,” we wrote in 2001.

Around the same time jewelers began to take the World Wide Web seriously, they also noted the emergence of a powerful new demographic known as Generation Y, aka millennials, a group of young people 72 million strong and defined by “the Internet, digital technology, and domestic terrorism,” we wrote in 2001.

Once we’d entered the aughts, diamonds came under increasing scrutiny, as conflicts in Africa introduced the term blood diamonds into the jewelry lexicon. But the ongoing controversy didn’t derail bridal jewelry sales. Quite the opposite. By 2002, 81% of all brides received an engagement ring, with 74% of them being newly purchased diamond rings, totaling ring sales of some 1.7 million. The average expenditure was $2,000.

When 2010 rolled around, bridal jewelry was unquestionably the backbone of a retailer’s business. JCK queried 100 store owners in January of that year and found that nearly half of all respondents’ sales were bridal in nature.

When 2010 rolled around, bridal jewelry was unquestionably the backbone of a retailer’s business. JCK queried 100 store owners in January of that year and found that nearly half of all respondents’ sales were bridal in nature.

Looking back on JCK’s coverage of the category, it’s clear that much about the wedding jewelry business has changed in the last half-century—starting with the tactics retailers employ to court couples. The ubiquity of mobile devices means retailers have to capture a couple’s attention on the go, with responsive websites that work well on small screens. Then there’s the undeniable impact of social media, represented by young people’s fixation on Instagram.

But the bridal sector—now termed the wedding category, in deference to the increasing importance of the LGBTQ market in the wake of the Supreme Court’s landmark 2015 decision to legalize same-sex marriage—remains a sales and marketing pillar for jewelers. And even though the trade now has its eyes firmly trained on millennials and Gen Z—two famously hard-to-pin-down demographic groups that will soon represent more than two-thirds of total global diamond jewelry demand, according to De Beers—our retrospective has taught us something essential: Diamond engagement ring sales are forever.

But the bridal sector—now termed the wedding category, in deference to the increasing importance of the LGBTQ market in the wake of the Supreme Court’s landmark 2015 decision to legalize same-sex marriage—remains a sales and marketing pillar for jewelers. And even though the trade now has its eyes firmly trained on millennials and Gen Z—two famously hard-to-pin-down demographic groups that will soon represent more than two-thirds of total global diamond jewelry demand, according to De Beers—our retrospective has taught us something essential: Diamond engagement ring sales are forever.

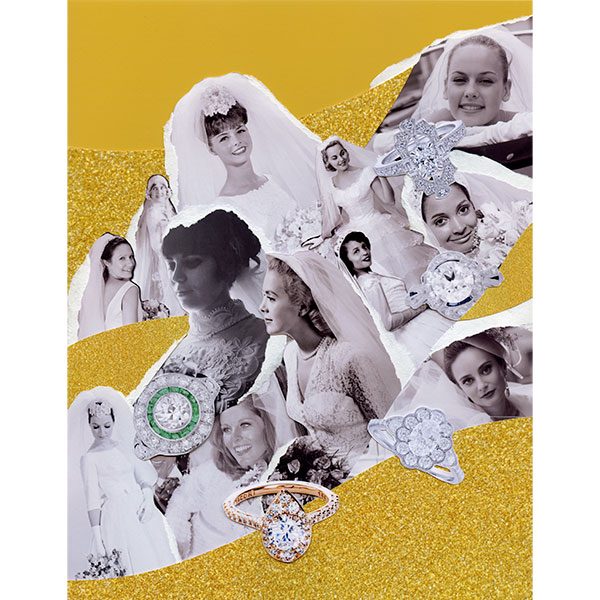

Illustration by Maxwell Burnstein

Illustration jewelry: Platinum Art Deco ring with 0.55 ct. diamond center, 0.25 ct. t.w. channel-set emeralds, and 0.36 ct. t.w. diamond accents, $18,500, rauantiques.com; Duchess Art Deco 14k white gold oval halo ring with 0.56 ct. t.w. diamonds, $2,350, gabrielny.com; Rafaelia Art Deco ring with old European–cut diamond and single-cut diamond and synthetic sapphire accents in platinum, $17,500, brilliantearth.com; 14k white gold floral oval halo with 0.63 ct. t.w. diamonds, $2,100 (without center stone), imaginebridal.com; Inflori pear-shape ring in 18k rose gold with 0.63 ct. t.w. diamonds, $4,090 (without center stone), tacori.com

Illustration jewelry: Platinum Art Deco ring with 0.55 ct. diamond center, 0.25 ct. t.w. channel-set emeralds, and 0.36 ct. t.w. diamond accents, $18,500, rauantiques.com; Duchess Art Deco 14k white gold oval halo ring with 0.56 ct. t.w. diamonds, $2,350, gabrielny.com; Rafaelia Art Deco ring with old European–cut diamond and single-cut diamond and synthetic sapphire accents in platinum, $17,500, brilliantearth.com; 14k white gold floral oval halo with 0.63 ct. t.w. diamonds, $2,100 (without center stone), imaginebridal.com; Inflori pear-shape ring in 18k rose gold with 0.63 ct. t.w. diamonds, $4,090 (without center stone), tacori.com

(Illustration photos, top row, from left: Stockbyte/Getty; Old Visuals/Alamy; Classic Stock/Alamy; Classic Stock/Alamy; Hitoshi Nishimura/Image Bank/Getty; bottom row, from left: H Armstrong Roberts/Retrofile/Getty (2); no credit; George Marks/Retrofile/Getty; Afro Newspaper/Gado/Getty; H Armstrong Roberts/Retrofile/Getty; Bottom, Right: Andrew Maidanik/Moment Open/Getty)

(Bridal photos and ads, from top: Advertising Archives; H Armstrong Roberts/Retrofile/Getty; no credit; V&A Images/Alamy; no credit; Advertising Archives; Francois Durand/Getty)