Over the past 150 years, which technological innovations have most improved the jewelry business? We vote for these 10.

Although human beings have adorned themselves with jewelry for millennia, the ways technology has shaped the modern jewelry business are readily apparent in the pages of 150 years’ worth of JCK. Technology we now take for granted—be it jewelry-centric, like pavé setting, or relevant to retailers of any consumer goods—could shift the nature of the business in ways early craftsmen, watchmakers, and jewelers never anticipated.

At each turn, JCK and its numerous predecessors could be found at the forefront, patiently explaining to readers how electric wiring and bells could deter theft, how war revolutionized the way we view timepieces, and how an invisible network of digital connectivity could usher in an entirely new format for making sales.

Below are the top 10 technological innovations since JCK’s founding in 1869—and snippets of how we described those marvels when they made their respective debuts.

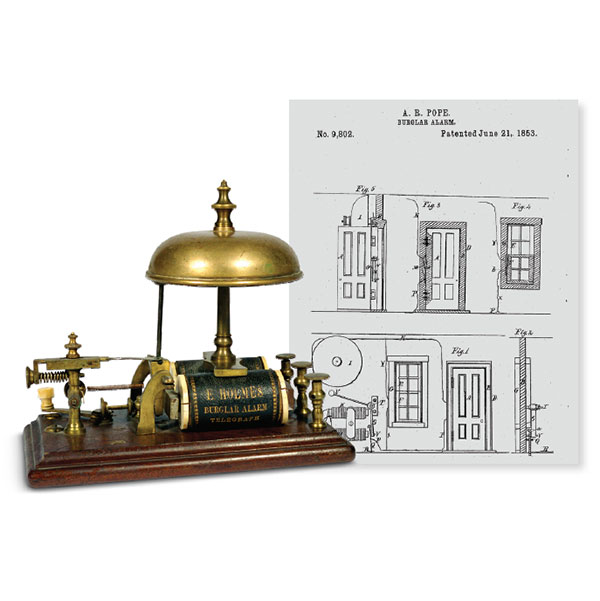

1. Burglar Alarms

1. Burglar Alarms

These alarms—which became available in the late 1800s to shopkeepers in big cities alongside the rise of phone and electrical line networks—led to a sea change in retailers’ ability to thwart thieves. Many magazine articles from the era that mention burglar alarms include a line or two about how they work, introducing them to readers who might not have been familiar with the technology. One feature from 1899, “The Holmes Burglar Alarm Worked to Perfection,” references the name of the inventor, entrepreneur Edwin Holmes. In an issue from 1891, a short item whimsically titled “The Burglar Alarm Worked Charmingly” tells the story of two Milwaukee jewelers who wanted to see if their “automatic burglar alarm” really worked—so they broke into their own store. When the authorities “caught” the pair, The Jewelers’ Circular and Horological Review said, “it took several minutes of active talking and explanation before the guardians of the law were convinced that the members of the firm in question were not burglars.” Jewelers, don’t try this at home.

2. Cash Registers

2. Cash Registers

The first patent for a cash register—which had metal keys stamped with -denominations and a bell to ring up sales—was filed by Ohioans James Ritty and John Birch in 1883. The next year, the National Cash Register Co. was formed; the first electric cash register came along in 1906. Three decades later, the National Cash Register Co. ran a full-page ad in The Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone, promising to reduce errors and make bookkeeping easier. “We have eliminated mistakes, and therefore increased the efficiency of our office,” an effusive testimonial letter read. “We are able, at any time, to obtain a picture of the day’s business”—an unremarkable thought now, but a marvel back then.

3. Pavé Setting

3. Pavé Setting

In an 1893 issue, The Jewelers’ Review described this breakthrough in craftsmanship: “From Oriental and Italian jewelry the Bohemians learned the Pave method.” (The term comes from the French for “to pave”; there was no accent on the e in those early years.) The article explained how the gems were mounted and set in a way that would secure them without the “teeth” of a prong setting: “This proved not only to be durable, but allowed the utmost variation of form, so that the invention may be considered the foundation of the present industry.” The pavé setting offered another key benefit: Metalsmiths could utilize gemstones that were too small to be secured by prongs, expanding their stylistic options tremendously and giving them a more affordable way to create eye-catching, expensive-looking pieces. That trend endures today, fueling the tremendous popularity in recent years of halo engagement rings.

A multigem butterfly brooch by pavé master JAR; sold at Christie’s for $407,237

4. Wristwatches

4. Wristwatches

Early iterations of “wristwatches” were more like bracelets and were considered jewelry—for women. That changed around 1914, when military pilots needed to be able to coordinate maneuvers with their fellow airmen. Instead of pulling out and opening a pocket watch, they began tethering timepieces to their wrists or thighs. There was initially considerable skepticism that this trend—ridiculed by “cartoonists and joke smiths,” as The Jewelers’ Circular and Horological Review noted in February 1917—had staying power. The magazine, however, was an early proponent, running an article, “The Time to Push Wrist Watches,” in that same issue. “Real soldiers wear wrist watches,” assured editors, who suggested the following copy for merchandising purposes: “They are manly watches for manly men.” A sidebar showed retailers how to capitalize on this trend, confirming that “the wrist watch is not an effeminate article.”

5. The Flame Fusion Method

5. The Flame Fusion Method

The 20th century began with the invention of the Verneuil process, aka flame fusion, the first economically feasible, scalable process for manufacturing simulated red rubies. The 1902 breakthrough formed the foundation of techniques for manufacturing synthetic gemstones—a topic of great interest to early readers—still in use today. In an 1893 article about the invention of simulant diamonds that would come to be named moissanite after inventor Henri Moissan, The Jewelers’ Review wrote, “For centuries it was the dream of the alchemists to change baser metals into gold. This has been succeeded in the scientific world by an effort to produce artificial diamonds.” The article explained Moissan’s discovery and ended with this philosophical musing: “It is another evidence that the earth has few secrets which man, by persistent effort, cannot wrest from it and adapt to his own uses.”

Cushion halo ring by moissanite creator Charles & Colvard

6. Air Conditioning

6. Air Conditioning

A/C revolutionized retail by transforming stores into cool, crisp oases in the sweltering summer months. A feature in the June 1936 issue began with the warning, “The dog days are coming. It will be a matter of only a week or so until the populace will be ‘hot under the collar’.… The progressive jeweler, however, will find it no longer necessary to let his trade go to the bow-wows.” The piece touted a mechanism that could operate “automatic and practically clocklike in precision in maintaining the atmosphere most agreeable with outside climatic conditions,” and predicted—correctly—that the technology would “revolutionize merchandising in all fields.”

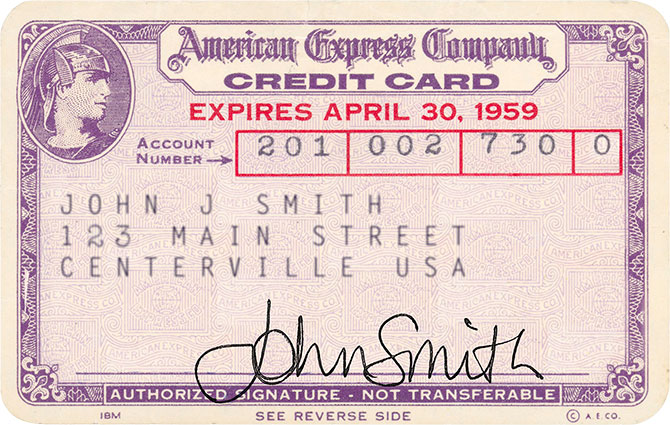

7. Credit Cards

7. Credit Cards

Today, Americans are used to buying on credit with a swipe, dip, or tap. But prior to the debut of the Diners Club card in 1950, credit was perceived as unseemly and beneath the dignity of affluent consumers. It was also much more individualized; back then, jewelry store credit cards weren’t connected to any larger payment networks such as Visa or MasterCard, or issuing banks that would absorb charge-off losses—and charge interest. In fact, charging interest was discouraged, as it was seen as cheapening the offer of credit. A 1948 case study in The Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone profiled a jewelry store that managed to solve “the problem of how to make credit attractive to the discriminating customers who comprise the clientele of this high-class jewelry store,” and explained how retailers could avoid “the stigma of ‘cheapness’ attached to credit selling.”

8. Quartz Watches

8. Quartz Watches

Invented by Seiko in 1969, the quartz watch set off a seismic shift in the industry—one that threatened manufacturers and sellers of mechanical watches (which a 1973 Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone article called “tick-tocks”). Not only did the timepieces send the Swiss industry into a tailspin, forcing thousands of companies out of business over the ensuing decade, but U.S. retailers and watchmakers also had to reckon with a whole new repair regime. Although JCK (perhaps grudgingly) conceded that “electronic watches create consumer-interest magic,” the unease with which jewelers first approached this radical answer to mechanical timekeeping peeks through. “Electronic watches account for only 1% of Swiss watch production. But that’s about 50% more than a year ago. And, every quartz watch exhibitor insists, this is the year of full-scale production.” Who could’ve guessed that in the 1980s, Nicolas G. Hayek’s Swiss-made, quartz-powered Swatch watch would be the catalyst for a mechanical watchmaking renaissance, creating a now $21 billion market?

Special Swatch 1983 Jelly Fish watch

9. Video Surveillance

9. Video Surveillance

The burglar alarm was a boon for jewelers because they could notify authorities of a crime in progress, ideally in enough time to foil the thieves. But if the crooks escaped, they could remain anonymous. A century later, cheap, user-friendly security cameras changed all that. A September 1975 JCK article explained this groundbreaking new technology, detailing how cameras were installed and positioned, and—just imagine!—snapped images every 30 seconds, providing a sort of jerky, time-lapse viewing (film was only developed if a crime took place). Experts even predicted that real-time monitoring would grow in popularity, with it becoming second nature for jewelers to keep one eye on a closed-circuit video screen most of the time. “We’re a nation that has grown accustomed to watching TV while working,” a Panasonic exec told us. “The average housewife can prepare dinner, do the wash, and still tell you everything that happened on her favorite soap opera.” Dated gender references aside, he never could have imagined how prescient his comments turned out to be.

10. The Internet

10. The Internet

Although the bones of what we now know as the internet were developed in 1983 as a research tool for academic institutions to share information, it was only in 1989 that the “www” prefix was invented, and the World Wide Web as we know it was born. The concept of digital communication—never mind the now-ubiquitous e-commerce—took some getting used to. In January 1995, we profiled the owner of Chicago’s Steve Quick Jeweler in an article called “Jewelry in Cyberspace.” An early adopter of e-commerce, Quick let customers order over the “net,” JCK reported (yes, we used quote marks). But the process wasn’t as streamlined as it is today; he had to manually verify each customer’s credit information. (Quick told JCK he found internet users to be “very interesting people from extremely diverse backgrounds.”) The same article claimed that the “Internet has more than 20 million users worldwide.” Today’s estimate? About 4.2 billion.

(1: Sparkmuseum.org; 2: Bettmann/Getty; 3: Christie’s Images Ltd.; 6: The Denver Post/Getty; 9: Ian McKinnell/Photographer’s Choice/Getty; 10: Hero Images/Getty)