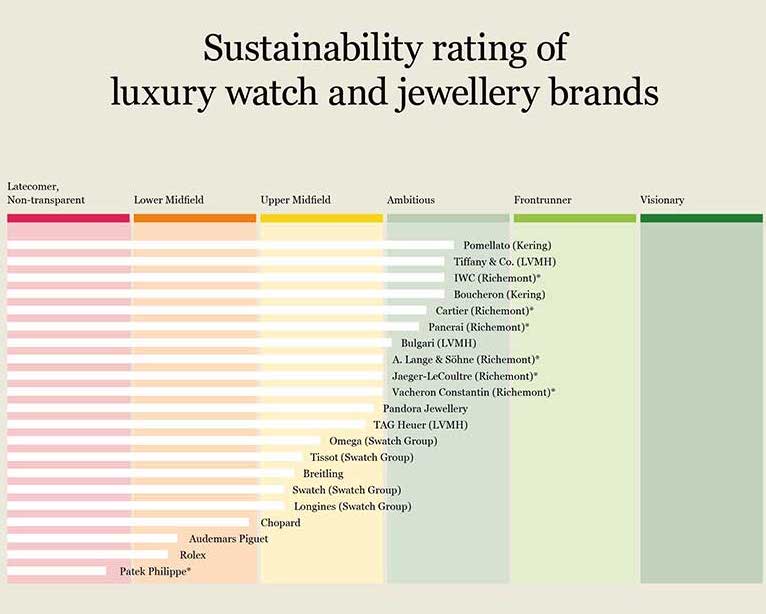

A new World Wildlife Federation (WWF) report says that watch and jewelry industry sustainability efforts “leave much to be desired,” but it ranked Pomellato, Tiffany, and IWC Schaffhausen tops among 21 brands studied.

Damian Oettli, head of markets at WWF Switzerland, tells JCK the jewelry and watch sector made a lot of progress in sustainability since the WWF’s last report in 2018, but it lags behind other industries such as automobiles and food, which have a more complex supply chain than the jewelry and watch business.

“Things have improved [with watch and jewelry brands], but there’s still far to go,” he says. “[Compiling the report] five years ago, there just wasn’t anyone to talk to. We would get communications officers, who would say, ‘Look at this wonderful ocean project—that’s our sustainability effort.’

“Today, almost all the brands have sustainability officers. They just need to do more. The watch and jewelry industry is still at its first steps.”

While no jewelry brand’s sustainability rating was high enough to land in the WWF’s two top tiers (of “visionary” and “front-runner”), Pomellato, Tiffany, IWC, Boucheron, Cartier, Panerai, and Bulgari all earned its third highest ranking, “ambitious.” Every one of those brands is owned by one of the three main luxury conglomerates—LVMH, Richemont, or Kering.

Four Swatch Group–owned brands (Omega, Tissot, Swatch, and Longines) received lower ratings, which put them in the fourth of the WWF’s six tiers. Privately held watch brands Chopard, Audemars Piguet, and Rolex landed in the second-to-bottom category, while Patek Philippe got the lowest ranking, “nontransparent.”

“Most of the [luxury] conglomerates are publicly held—they have to report to investors—while the other brands are privately owned family businesses, where it depends on whether the family is concerned about sustainability or not,” says Oettli.

Pandora and Breitling earned only middling scores, even though both brands have touted their sustainability credentials.

“It is common knowledge that marketing activities on sustainability aren’t a very good predictor of real performance,” says Oettli. “Sometimes they match, but it’s not a given. Marketing people often pick out one or two good stories and sell them well. There needs to be people looking behind the facade and seeing what’s going on.”

Oettli says the WWF has yet to study the ecological impact of lab-created gems (which Pandora and Breitling use in certain products). “Lab-grown can score better,” he says. “They are not flawless—they also have a footprint and need raw materials.

“There’s a difficult ethical question on what happens to those communities whose livelihoods depend on diamond mining. That’s a trade-off that needs to be looked at. As with many issues, there’s always two sides of the [coin].”

The report says that “recycled gold” claims by watch and jewelry brands such as Pandora must be “viewed with caution.”

“Because it sounds so attractive, many producers just call a lot of things ‘recycled gold,’” says Oettli. “The question is, What definition do you apply? It needs to be post-consumer to be called recycled gold. You just can’t run it twice through the same refinery and say, ‘It’s recycled now.’”

He notes that recycled gold suppliers can be less transparent than mines. “The traceability isn’t guaranteed. Everyone can claim their gold is recycled, and you don’t really know what they’re getting.”

The report warns the public to be on guard for “greenwashing” and takes particular aim at the terms “climate-neutral” and “carbon-neutral.”

“Companies claiming carbon- or climate-neutrality will say, We have these emissions, but it’s okay because we are planting some trees over there,” Oettli says. “Since the [2015 Paris climate accords], every company is called to reduce emissions directly.”

In perhaps the biggest surprise, seven brands refused to provide information to the WWF. “No company is forced to talk to us,” Oettli explains. “But that’s specific to the watch and jewelry industry. They experience an NGO looking into their business as offensive and feel threatened. In most modern companies, they appreciate that and see it as an opportunity. They are getting an analysis of their business from a sustainability perspective, which would cost them tens of thousands of dollars if they had to buy it from a consultancy. They are getting it free of charge from us.”

He says companies—both small and large—need to focus on the areas where they have the most impact. “What we see a lot is, at the beginning, companies will just have someone who likes planting trees or wants to reduce paper consumption,” says Oettli. “But they have a blind spot for what they really should look at—traceability, transparency, and production methods.”

(Photo and chart courtesy of WWF Switzerland)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine