In June 2006, I published a story in the International Herald Tribune—later rebranded the International New York Times—about the jewelry trade’s nascent efforts at documenting the gemstone supply chain.

“Tracing the path of a colored stone through the vast and largely unpoliced gem trade is a complicated affair, even for the experts,” I wrote. “Unlike diamonds, most of which are marketed by a handful of mining juggernauts through a supply chain that is under increasing scrutiny, gems follow a haphazard and opaque route to market that lends itself to smuggling.

“That has not discouraged a growing number of gem cutters, dealers, jewelry manufacturers and retailers from demanding to know that the gems they buy and sell have been handled with social and environmental integrity.”

A dozen years later, the gem trade is still grappling with how to bring its products to market in a transparent and sustainable manner—so much so that if I were to tackle the story today, I could use the exact same lede.

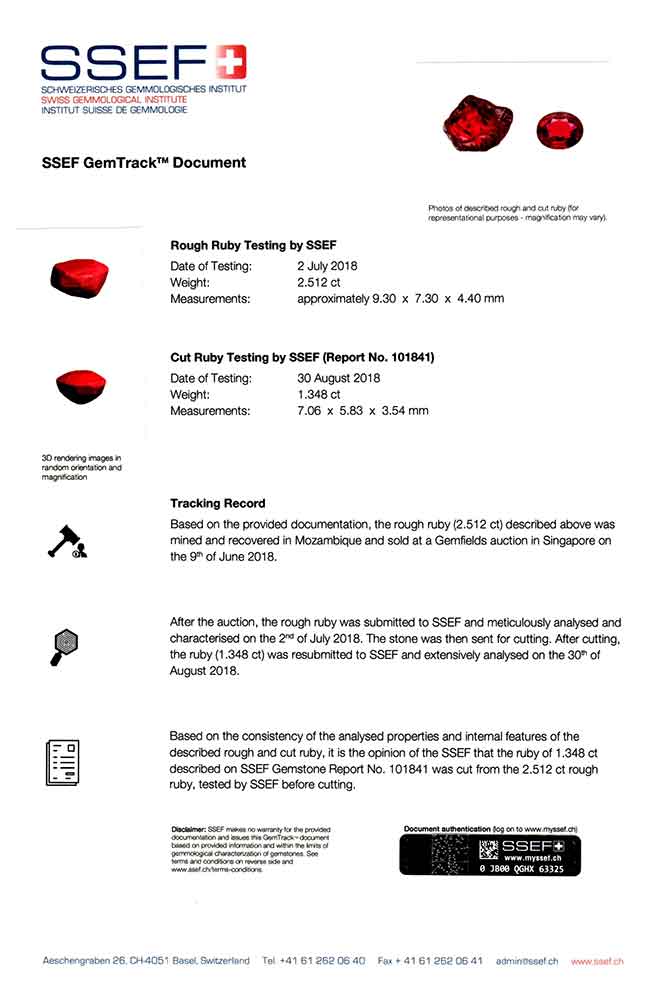

Take the latest such effort to appear on my radar: Ressigeac Gems’ new traceability project, in collaboration with the Swiss Gemmological Institute SSEF.

In June, Philippe and Veronica Ressigeac, founders of Bangkok-based Ressigeac Gems, purchased a lot of rough Mozambican rubies at the Gemfields auction in Singapore and embarked on a pilot project with SSEF to document each step of the rubies’ journey to market. (The former Gemfields employees met three years ago when Philippe was stationed in Mozambique and Veronica in London.)

“The whole gemstone industry is trying to shift direction toward traceability,” says Philippe. “A lot of innovations have been implemented for diamonds but it is just starting for colored gemstones as there are a lot of challenges to overcome.”

Earlier this month, the lab created an SSEF GemTrack Document that includes a record of when the rough stone noted in the report left the mine, when it was submitted to SSEF, if it was recut after the lab analysis, and whether or not the recut stone matched the rough that had already been analyzed.

“We work mostly with luxury brands and the general impulse for going toward traceability and sustainability is coming from the end consumer of luxury products, which are more and more requesting transparency on the supply chain and want to know that the stones they purchased are not coming from a conflict area and/or damaged the environment,” Ressigeac says.

He adds that the firm, which specializes in fine unheated/untreated rubies, sapphires, and semiprecious gems over 1 ct. in size, intends to develop similar tracking reports for other types of gemstones.

It’s a worthy cause and I look forward to seeing how the project evolves. Though I can’t help but wonder why it still feels so pioneering.

Over the past decade, the gem trade has failed to gather the momentum it needs to make traceability standard operating procedure. I understand the gemstone supply chain is considerably more fragmented and opaque than the diamond or gold supply chains. But it seems the greater obstacle is apathy among dealers and retailers unwilling to demand their suppliers provide the documentation required to prove how a gem has journeyed from mine to market. (There are a handful of glaring exceptions—notably, Eric Braunwart of Columbia Gem House in Vancouver, Wash., a leader in the market for fair trade gems.)

With the advent of blockchain technology (soon to be applied to the gem trade thanks to a number of initiatives brewing for 2019), the industry has the opportunity to finally wrestle this issue to the ground. I hope enough people make that happen—and that I’m not lamenting the lack of collective progress we’ve made in 2030.

Top image: Rough and polished rubies, courtesy of Ressigeac Gems

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine