The list of celebrated Black jewelry designers in American history is distressingly short.

This is not because Black Americans haven’t been participants in the jewelry industry—they have. But prior to the mid-20th century, Black designers and jewelry artisans usually worked in anonymity, their expertise and artistry fueling the bottom lines and good reputations of white entrepreneurs, not their own. These artists also faced countless obstacles in accessing education, apprenticeships, jobs, and resources, as codified racism in America—beginning with slavery and reaching a painful crescendo during the Jim Crow era—conspired to keep Black innovators in every artistic medium off the radar.

“I think that the identities of a number of skilled Black artists and bench jewelers have been lost to time,” says Emily Waterfall, Bonhams’ director of jewelry in Los Angeles. “I hope moving forward that we’ll start uncovering more of their names. It’s our responsibility to try.”

During the last century, barriers to entry to the U.S. jewelry industry tightened for all newcomers, as dynastic family businesses and close-knit professional communities increasingly dominated the industry. For Black designers and bench jewelers, who usually came to the industry alone and without family or community connections, these barriers were particularly pronounced. As entrepreneurs built what would become today’s heritage brands, Black professionals fulfilled key roles, but were rarely the superstars.

Despite the challenges (many of which still persist today), a handful of Black American designers attained both critical and commercial success in their careers. Here are three who belong in the canon of all-time greats.

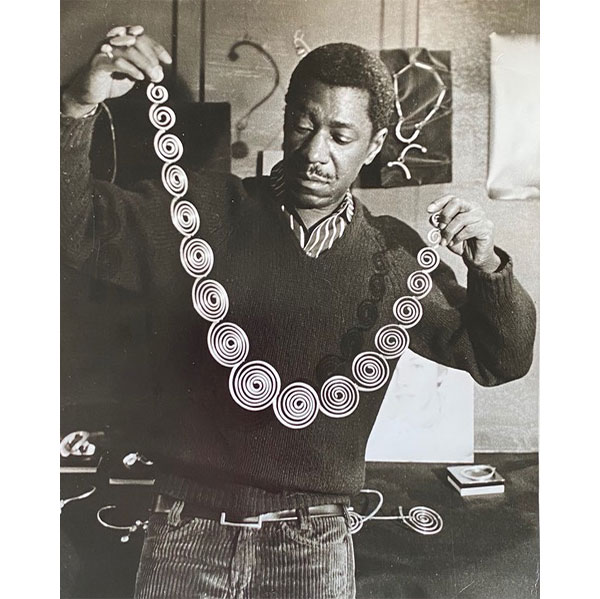

Art Smith

Modernist jewelry designer Art Smith was one of the major 20th century jewelry artists. And, Waterfall says, “He’s also one of few whose [all-metal] work can sit alongside the gem-encrusted pieces I sell.”

Smith was born to Jamaican parents in Cuba in 1917, but his family settled in Brooklyn, N.Y., in 1920. He received a scholarship to Cooper Union, where he was one of only a handful of Black students. After college, he also took a night course in jewelry making at New York University, and around that time he struck up a friendship with Winifred Mason Chenet (more on Mason Chenet, below), who became his mentor.

Mason Chenet had a small jewelry studio and store in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village neighborhood, and Smith became her full-time assistant. In 1946, Smith opened his own studio and shop on Cornelia Street in the village “with the financial assistance of a near-stranger who wished to undermine Mason because of bad feelings over business transactions,” reads the catalog from a show on Smith, “From the Village to Vogue: The Modernist Jewelry of Art Smith,” which was held at the Brooklyn Museum in 2008.

After his storefront windows were smashed and he was threatened by residents of the heavily Italian neighborhood, Smith moved his shop to 140 W. Fourth St. in Greenwich Village. “He operated out of a storefront selling affordable jewelry,” Waterfall says. “It was not jewelry for the elite. But he personally elevated it to an art form. He created interest in it and he made a brand for himself.”

His career began to take off, and in addition to selling directly, he sold to craft stores in Boston, San Francisco, and Chicago. By the mid-1950s he was wholesaling to Bloomingdale’s and Milton Heffing in Manhattan, James Boutique in Houston, L’Unique in Minneapolis, and Black Tulip in Dallas.

Socially, he fell in with leading Black artists of the day—including writer James Baldwin, composer and pianist Billy Strayhorn, singers Lena Horne and Harry Belafonte, actor Brock Peters, and expressionist painter Charles Sebree—and through connections designed jewelry for several avant-garde Black dance companies (which led to Smith creating a series of fantastic large-scale pieces).

In the early 1950s, Smith’s work was shown in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, and in the 1960s, he received a prestigious commission from the Peekskill, N.Y., chapter of the NAACP to design a brooch for Eleanor Roosevelt, to name one project. He also made cufflinks for Duke Ellington that incorporated the first notes of Ellington’s hit 1930 song “Mood Indigo.”

In 1969, Smith was the subject of a one-man exhibition at New York’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design), and in 1970 he was included in “Objects: USA,” a large traveling exhibition organized by Lee Nordness, an influential early dealer in craft objects.

“His pieces were very powerful and profound,” says Waterfall. “He found inspiration in artist Alexander Calder. Calder had this jewelry on display during his art shows—it was a thing you could have and take with you, a small token to purchase. And I think across the board, artists began creating jewelry that was more wearable arts.”

Smith died in 1982, but his work—bold and fluid wearable sculptures—continues to inspire designers today.

So much so, the Art Smith Memorial Scholarship Fund was established in his name last year by a group of 50 jewelry industry brands—and spearheaded by JCK jewelry director and For Future Reference cofounder Randi Molofsky—to fund a $50,000 Endowment at New York City’s Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) that creates ongoing scholarships and mentorships to support Black students attending FIT’s jewelry design program.

Winifred Mason Chenet

Winifred Mason Chenet, Art Smith’s mentor, was born in 1918 in Manhattan to West Indian parents and is considered by many to be the first commercial Black jeweler in the U.S.

Like Smith, she worked in less “precious” materials—bronze, copper, and silver—but the creativity and articulation in her pieces elevated her work to fine art.

“I find her work really inspiring,” says Waterfall, “and there’s an elegance in the materials that she chose. Her work [illustrates] the idea that it’s not the value of the materials that dictates the value of a piece—it was the overall piece. And I think in showing that, she’s part of that movement that crossed that bridge between art on a wall and something you could wear.”

Mason Chenet received a B.S. in English literature in 1934 and went on to receive an M.A. in teaching from New York University in 1936. She taught metalworking at youth program Junior Achievement, which is where she met Art Smith. She taught for years, but her heart was in designing. She received a grant from the Rosenwald Fund to gather folk material and basic art patterns used by Black West Indians and incorporate them into her jewelry design. The research for this work took her to Haiti, and while there she met her husband, Jean Chenet.

Mason Chenet never repeated her works, so every piece she made was one-of-a-kind. And when she couldn’t find a proper instrument for her work, she created it herself. She opened her own studio in Greenwich Village in the early 1940s, and her jewelry was sold at Lord & Taylor, among other department stores. She was also a custom designer, and created pieces for luminaries including Billie Holiday. By the late 1940s, 10 exhibitions of her jewelry had already been staged, including one-woman shows in Milwaukee and Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Her husband was tragically murdered in 1963. Under her married name, Winifred Chenet, she sold voodoo-inspired jewelry in Haiti, and also operated a store in New York selling Haitian art. Mason passed away in 1993, but her influence has been far-reaching. Shades of Mason Chenet’s layered, linear work are evident in iconic jeweler Robert Lee Morris’ pieces, and in the chic, cutout designs of modern jewelry designers including Annie Costello Brown and Ariana Boussard-Reifel.

Bill Smith

Jewelry designer Bill Smith, who was born in 1936, was the first Black recipient of a Coty Award, and designed jewelry for companies including Coro, Richelieu, and Cartier.

According to an article in the Washington Afro-American newspaper published in 1970, Smith went to Indiana University, where he studied art and dance, and in 1954 he moved to New York to further his study of dance—though he ultimately decided to focus on jewelry design. In 1958, he set up a workshop in Manhattan so he could create jewelry for companies while studying dance part time.

In June 1968, Smith was promoted to vice president of Richelieu, at that time the second largest jewelry firm in America—this after only two months with the company as its head designer. He later created all the jewelry for the Broadway production of Coco, a stage musical about the life of Coco Chanel starring Katharine Hepburn. When he won the Coty Award in 1970, his winning jewelry was African-inspired, and featured tassels, leather, and cord.

One of the splashier moments in Smith’s career occurred when he posed with model Naomi Sims for a spread in the April 1972 issue of The Look magazine (Sims wore one of his 18k gold cuffs designed for Cartier). The model had reportedly introduced him to Kenton Corp., which set up Bill Smith Design Studios Inc., with Smith as president. It was this company with which he created jewelry for Cartier and leather accessories for Mark Cross.

Because Smith designed so much for other companies, he’s not as well-known as Mason Chenet and Art Smith (you can glimpse the occasional Bill Smith for Richelieu piece on eBay and Etsy). But while working in the ateliers of major brands and manufacturers, he helped usher design originating in African nations into high-end American jewelry.

Top: Art Smith (photo courtesy of the estate of Art Smith)

Follow Emili Vesilind on Instagram: @emilivesilind

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine