When people think of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City, they tend to think of dinosaurs.

But the museum also houses an impressive collection of thousands of gems—some of which date back even further than the brontosaurus. Until recently, these specimens were housed in the museum’s Harry Frank Guggenheim Hall of Minerals and the Morgan Memorial Hall of Gems.

Both those halls opened in 1976—and, in recent years, they pretty much looked like it. And while some appreciated their vintage charm, to others, they looked downright prehistoric.

In 2017, the AMNH said goodbye to Harry Frank, Morgan, and the halls’ classic ’70s carpet. The gem and minerals areas have been closed for renovations for the last three-and-a-half years—longer than expected, in part because of COVID-19.

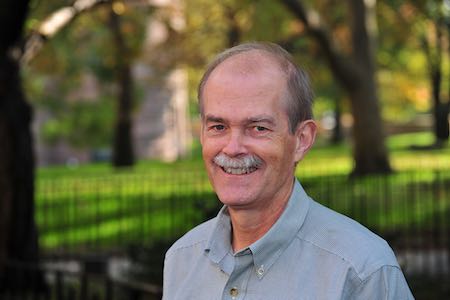

On June 12, the museum will officially open to the public its revamped and refurbished 11,000-square-foot gem and mineral area, now called the Allison and Roberto Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals. JCK recently talked with its curator, George E. Harlow, who spoke about the new hall like it was a gorgeous present he couldn’t wait for the world to unwrap.

Here, Harlow, who is also curator of the museum’s department of earth and planetary sciences, discusses the new hall’s “mind-blowing” exhibits, the trials and tribulations involved in refurbishing during COVID-19, and the deeper ideas he wants people to take away.

JCK: What can people expect to see in the new gem hall?

George E. Harlow: If you’re familiar with the old gem hall, it’s the same concept, but bigger and better. We will have more stories about gems, more images about the pieces, more information about where they come from and where they were made.

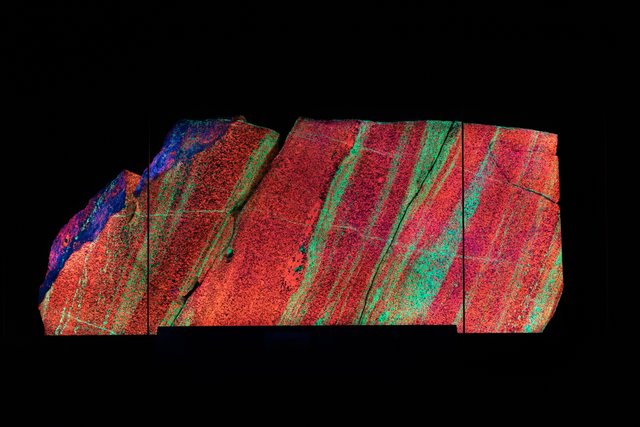

There are amethyst geodes at the entrance that are quite mind-blowing. We have a panel of fluorescent rock that glows in shades of orange and green from Sterling Hill, N.J., that’s about 14 feet high. We have two large collections of gems donated by J.P. Morgan.

We have the very first cut sapphire found in the United States. We have gems from Maine and California. We have a special case of New York City minerals, including the famed Subway Garnet. It’s about nine pounds. It’s a well-formed almandine garnet. It’s the biggest known mineral that was found in New York. It was found in 1853 on West 35th Street during an excavation for a sewer. We have approximately 400 minerals from New York City, including some gems, like some garnets and quartzes. There is chrysoberyl from places like West Paterson, New Jersey.

[Editor’s note: According to a press release, other items at the hall include the legendary 563 ct. Star of India sapphire, the 632 ct. Patricia Emerald, and a 110 ct. diamond Organdie necklace.]

How long did it take you to put this all together?

That’s a long story. When I came in here, I inherited the hall and tried to improve it. We changed the carpet three times. By the time we got around to refurbishing it, we decided it needed a total replacement.

I got the go-ahead around August 2014. We went through several generations of designs. It’s basically organized schematic[ally by] mineralogy. The connection with chemistry is much stronger.

In 2017, we closed the hall in the late fall. We removed everything—some of those items had been in those cases for 45 years. We were hoping to reopen in December 2019. Well before COVID, it became clear that was unrealistic. In late 2018, we hoped to open in 2020. That was the target before COVID, but then we had to step away. My group came back in the summer of 2020. We had hoped to be able to open in the fall of 2020, but we didn’t get approval to reopen. So now June 12 is the public reopening.

What kind of message would you like people to take away from the new hall?

One of the issues is that minerals make up the majority of Earth, even in its deep interior. Minerals are important to all life forms. Our teeth use minerals. The shells of shellfish are made from minerals.

We want people to look at mineral evolution as a scientific concept. After the Big Bang, there was only hydrogen and helium. It took something like 200 to 300 million years for early giant stars to burn out and blow up to spew out heavier elements, like carbon and silicon, to create minerals. Prior to the formation of any planets, there were perhaps a dozen mineral species.

In 1976, when I first started working here, there were 2,500 known minerals. Now there’s 5,700. It’s not a dead topic.

There’s always been the fear that people think minerals are boring. We want to show that, no, they are not boring. We hope to be able to use this to teach earth science and make an attractive, interesting hall out of it.

Do you expect the hall to become more popular?

The previous hall was always one of the most popular halls in the museum. This is a brand-new, exciting place. People have been away from museums in general for a while so I think there is a lot of pent-up demand.

And you’re also going to have rotating exhibits in the Melissa and Keith Meister Gallery next to it, correct?

Right now, it’s Beautiful Creatures [a collection of jewelry inspired by the animal kingdom, curated by Marion Fasel]. We also have in the hall a Jonas Mine tourmaline that’s 180 pounds and 85 centimeters high, and Alan Bronstein’s Aurora Butterfly of Peace collection of colored diamonds. Those will run at the same time as Beautiful Creatures.

Our goal is to have changing exhibits. We have an expression: You visit the museum three times—once when you’re a kid, once when you’re a parent, and once when you’re a grandparent. Part of our goal is to get people to visit more. If you’re interested in jewelry, Beautiful Creatures is a can’t-miss exhibit.

[Editor’s note: Pre-COVID-19, this Manhattan parent visited often, and hopes to start doing so again soon.]

What other exhibits do you expect?

The other exhibits might not be jewelry. We might look at gems from a cultural perspective. Why is the whole gestalt of gems in Southeast Asia different from that of the West? We may look at where the resources come from. We may have something on being good stewards of the Earth when extracting materials.

Do you expect to see more jewelry in things like the gift shop?

I can’t really speak to what’s happening in the gift shop, but I’d like to do more with the industry. I feel 47th Street doesn’t even know where we are. You cannot see the variety of gems we have anywhere else.

You have been at the museum for four decades. Is this your crowning achievement?

I call it my odyssey. I gave it my best shot. There is a lot of me in it, but this was a team effort. Unfortunately, a lot of the people who did such hard work on it aren’t at the museum because of [layoffs related to] COVID. But we certainly hope to see more local people come in. About 30 percent of our traffic is from overseas. They won’t come back until people start flying again. But New York City is desperate for that level of activity.

What reaction do you expect people to have?

I think it’s a beautiful space to walk into. It looks much bigger now. The ceiling looks larger, the cases are better lit, and the specimens are mounted with clutch mounts.

I think people’s jaws are going to drop. There are certain objects that are truly remarkable. You are going to see things that you’re not going to believe.

(All photos by D. Finnin/courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine