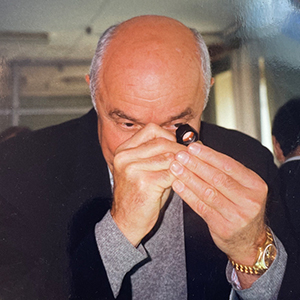

Marvin Samuels, the founder of Premier Gem in New York City, is one of the legends of our industry—and at 91, he’s as sharp as ever. Born in Scranton, Pa., he went into the diamond business at age 23, founding Premier in 1956. The company has been a De Beers sightholder since 1967.

Samuels talks with JCK about starting out, his memories of industry icons like Harry Winston and M.B. Zale, and his views of the jewelry business’ future:

How did you get started in the gem trade?

My brother had gone into the diamond business. Then when it was my turn to do something, I learned diamond cutting. I specialized in emerald cuts. [Cutter] Lazare Kaplan had developed the oval. He never patented it, so I started making it, too. People laughed at it. They called it the shmoval.

I was an okay cutter, but I didn’t really enjoy sitting at the bench. What I enjoyed was taking a rough diamond and creating a beautiful item. But I didn’t enjoy the work itself.

So when did you leave cutting?

By the 1950s, I started buying on my own. I’d buy from dealers who were bringing back rough from Belgium. After 10 years of struggling here in the States, I said, “I have to make a trip to Belgium. Why give these guys a profit?” For a while, I went to Antwerp almost every other week.

My forte was knowing where the diamond came from. I could look at a diamond and tell you if it was from Sierra Leone, Angola, or the Congo. I knew that certain goods would turn better color. I could see the nature of the material.

How did you begin to specialize in big diamonds?

We were one of the first in New York to trade in them, besides Harry Winston. One of the first big stones I bought was a 98-carat rough diamond. I paid $300,000 for it. That was a huge amount of money. After I bought it, I panicked. I called Gerald Rothschild, of I. Hennig. I knew Harry Winston would go to the [De Beers] sights in London, and said, “Gerald, you have to do me a favor. I need to talk to Harry Winston. Can you tell me what flight he’s on?”

He told me Winston always flew TWA. So I phoned TWA. In those days, you were able to call up and say you’d like to sit next to someone. They said, “Mr. Winston is sitting in first class.” Back then, I didn’t know what first class felt like. So I paid what was then a lot of money for me to sit in first class.

I got on the plane, and as I’m putting up my luggage, Winston said, “Marvin, what are you doing here?” I had him for eight and a half hours. He was in the window seat, and I was in the aisle seat. I said, “I just bought a 98-carat stone, and I can make a 50-carat emerald cut.” He said, “Listen to me. You’ll never sell it.” I went into a panic.

He said, “See if you can make two diamonds out of it.” I made one stone: a 47-carat emerald cut. No one wanted to buy it. At that time Christie’s was holding its first jewelry auctions. I went to Hans Nadelhoffer, the head of Christie’s Geneva, and he told me he’ll take it. He auctioned it off for $440,000. In the end I made a nice profit.

At what point did you become a De Beers sightholder?

In 1967. It took about 10 years. De Beers in those days couldn’t come to America, so it was challenging for them, because they didn’t know much about U.S. companies.

De Beers back then was a well-oiled machine. They knew when you made money, they knew when you lost it. If you went through a year where business was bad, they’d let you earn back what you lost.

You dealt with a lot of giants in the industry. What are some of your memories?

The diamond people in those days were powerhouses. I remember I once finished a blue stone, a 22-carat emerald. [Van Cleef heir] Claude Arpels came up to the office, and he went from room to room. I said, “What are you doing?” He said, “I’m looking for incandescent light. Colored diamonds are worn in a ballroom. In a ballroom, you have incandescent lighting.” I finally found an incandescent lamp, and he put the diamond under it. He said, “Not for me. It doesn’t look good in this light.” And he was right.

Morris Zale was another legend I had the privilege of not only knowing but being his partner. I will never forget when he gave me a tour of his facility in Texas, and I asked him, “M.B., how many people work here?” He looked me right in the eye and, deadpan, said, “About half.”

I had the good fortune to subsequently partner with Zale Corporation and with Louis Glick on what I consider to be one of my crowing achievements—the purchase of an 890-carat rough stone, which we cut to the 407.48-carat fancy color flawless Incomparable.

What do you see as the future of the business?

Today I’m not so sure I would be able to accomplish what I did. I was in the business before the color machine, before computers. I could buy big diamonds and know what you would get from them. I used my brain, because that was all I had.

The trust we used to have is gone. I used to be able to call up Robert Mouawad and tell him, “I have a big stone,” and he’d say, “I’ll join you if you want.” Because he trusted me.

I always found the business a lot of fun. It was challenging, of course, but it was fun. And I miss it.

(Photos courtesy of Premier Gem)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine