Last year, JCK declared lab-grown diamonds a “bandwagon.” As it turns out, the bandwagon was just beginning.

2018 has been the Summer of Lab. De Beers’ Lightbox brand may have been intended as the dam that would stop the rising tide of lab-grown diamonds. But it also might be the final torrent that unleashes the flood.

“De Beers is the big kahuna,” says Israel Itzkowitz, a veteran cutter who is now a consultant to grower Diamond Foundry. “They’re like Elvis. If they smoke pot, it gives everyone permission to smoke pot.”

Clive Hill, president of WD Lab Grown Diamonds, another grower, admits that at first, “the market was roped on its heels with Lightbox. That definitely slowed things down for a bit. But the people who are selling them are still selling them.”

When you add in the recent Federal Trade Commission Jewelry Guides revisions that favored the lab-grown sector—particularly its removal of the word natural from its official definition of diamond—it is a heady time for man-made companies. Not only do they think De Beers’ decision legitimized lab gems within the industry, it gave them more sheen with the outside world. Investment funds have been increasingly poking their heads around. One fund told JCK that it looked at the sector but decided against investing in it, as too many investors were already in it.

Trade analysts Chaim Even-Zohar and Ben Janowski now see the shift toward man-made as inevitable. “We are selling to the world’s largest manufacturers,” says Martin Roscheisen, CEO of Diamond Foundry. “In the past, that whole ecosystem in India was closed to us. Now, I believe, every single sightholder is thinking about it.” One-third of his company’s sales are now rough, he says.

More industry people are getting involved, too. The former president of Alrosa is starting a company. Hong Kong manufacturer Diasqua is connected to GoGreen Diamonds. Trade veteran Alexander Weindling is behind CleanOrigin, an e-tailer cofounded by Ryan Bonifacino, former chief marketing officer of Alex and Ani. Terry Burman, the legendary former CEO of Signet Jewelers, heads its advisory board.

“The industry should be glad that it’s me and Terry in this and not some yahoo with a sledgehammer,” says Weindling of his site. “We live in this house. We are not here to burn it down. But the mined industry needs to make room for us on the couch. If we stop the fighting and let the consumers do what they want, then we all can win.”’

There’s also talk of new growers. This week, Tokyo-based Pure Diamond Lab debuted with claims it can produce diamonds in colors “not seen in nature.” It’s also tracking its lab-growns via blockchain and funding the project with a cryptocurrency, an impressive melding of three corporate fads at once.

More retailers are getting behind the product as well. “I wouldn’t say [after Lightbox] my orders doubled overnight,” says Sehal Mody, chief operating officer of GoGreen Diamonds. “But it did help.”

Man-made gems are already available at big names like Helzberg, Reeds, Robbins Brothers, Samuels, Spence, and Borsheim’s. Other companies are, for now, staying on the sidelines—including Signet, which carries created colored stones. That said, Signet executives seemed more open to carrying lab diamonds after the Lightbox announcement than before, though only for fashion.

Chinese retailer Chow Tai Fook remains opposed: “We only sell real natural diamonds, [not] synthetics,” a spokesperson tells JCK. Luxury names like Tiffany & Co. and Van Cleef & Arpels also haven’t hopped on board, at least for the moment. “We know that some of the [high-end names] are getting into it,” says Roscheisen. “We can’t say who, but they are getting into it.” Hill similarly teases some “interesting mainstream” retailers will enter the market in the next few months.

Many independents have also become believers. Craig Husar, owner and chief romance officer (yes, that’s his title) of Lyle Husar Designs in Brookfield, Wis., says more than half his diamond sales are now created gems.

“The younger generation is usually pretty open,” he says. “The older customers are a little more suspicious, not quite sure. But we’re selling them across the board. We explain what the origin is. For most, it doesn’t matter. It’s like people don’t say, ‘I only want a natural pearl.’ They take a cultured pearl.”

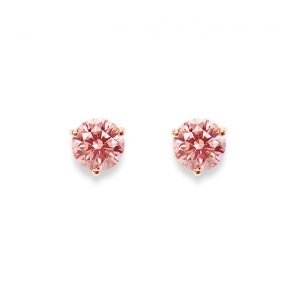

Ron Yates, owner of Yates Jewelers in Modesto, Calif., is enjoying healthy sales of lab-grown pinks.

“It’s something different. I tell customers that a mined pink will cost over $100,000. And these are $2,000. I’m trying to specialize, because otherwise it’s hard to set yourself apart from the big boys.”

On the other hand, Yates’ customers didn’t cotton to man-made colorless: “The price differential wasn’t big enough for them to rally around them.” Then again, he’s not a fan of them either. “I don’t know what the market will be like in a few years, so I don’t feel comfortable selling something that might be worth much less.”

That remains a key sticking point for many jewelers, especially how they will handle trade-ins. JCK has heard of retailers that have customers sign statements acknowledging that created gems might not hold their value.

For all this activity—and the increasing angst it’s causing the natural business—the overwhelming majority of diamonds sold at retail still come from the ground. De Beers’ chief financial officer recently told the Rapaport Research Report that the lab-grown market comprises about 3–5 percent of the industry. And CEO Bruce Cleaver told JCK that natural diamond sales in the first half of the year have been strong.

“The specter of lab diamonds flooding the market is way overblown,” says Jason Payne, CEO of Ada Diamonds, a lab-grown seller. “It’ll take many, many billions in capital and many decades before lab diamond production even matches natural production.”

Roscheisen, whose company is building a factory in Washington, agrees that growing is hard to scale. “The largest producer is maybe 100,000 carats a year. There are no six-figure producers of man-made diamonds.”

De Beers recently made a similar a point in a sheet distributed to sightholders: Lightbox aims to produce 100,000 cts. of rough in 2019 and 500,000 cts. by 2021. By contrast, it mines 34 million cts. out of natural rough a year, out of a total global production of 160 million.

Moreover, the lab sector, like all aspects of the industry, faces challenges—including all the companies coming into it. The industry has seen stampedes like this before: In 2000, scores of well-funded jewelry websites appeared on the scene. Few survived.

The increased competition could also hurt the stones’ margins—which some retailers view as a chief selling point (at least for them). They are already sold on Brilliant Earth, which one market participant called “the Blue Nile of lab-grown.”

Growers could also face legal entanglements. Even though it’s a tech business, diamond growers don’t typically talk much about their technology. That’s because, insiders say, diamond growing is pretty basic. It’s been around for decades. Some companies might produce more efficiently than others or boast their own special tweaks, but there is considerable sensitivity about intellectual property issues. De Beers’ Element Six has already sued IIa Technologies in a Singapore court for patent infringement. (IIa denies any infringement.) Hill, whose company licenses technology from the Carnegie Institute for Science in Washington, D.C., says he “wouldn’t be surprised” if more lawsuits spring up.

And finally, there’s the specter of Lightbox, which will debut in September, with a reported $8 million marketing budget. If, as promised, customers will be able to buy a 1 ct. white lab diamond for $800 (plus a mounting) with a click of a button, what happens to the market then?

According to analyst Paul Zimnisky, the overall price of lab diamonds has dropped over the last two years. After the Lightbox announcement, it sunk an additional 10 to 15 percent, with the biggest declines in the ½ ct. to 1 ct. range, he says.

Mody admits there was a post-Lightbox decline but says it wasn’t anything major: “They went down maybe 2 to 5 percent. You didn’t see a huge drop.” Others say prices have been stable, especially on the larger stones. Still, just about everyone agrees that the price jitters have made the market far more consignment-oriented.

All in all, the lab business has seemed superhot this summer. The challenge is to keep this growth spurt going through fall.

(Top: Image courtesy of ALTR Created Diamonds)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine