When it comes to legendary stones, it doesn’t get more real or rarer than the Koh-i-Noor. But just because the diamond, currently enshrined in the Tower of London, a star attraction among the British crown jewels, is authentic, it doesn’t mean the stories that have over the centuries attached themselves to the prized gem are equally genuine.

Celebrated historian and writer William Dalrymple and BBC journalist/on-air personality Anita Anand are the coauthors of Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond, the most interesting diamond-centric book you may not have read in 2017. Together they attempt to unwind the snare of half-truths, honest mistakes, and fanciful inventions that have become not only part of the diamond’s pedigree, but also have fueled controversy and conflict over its ownership and proper home—from ancient times up to the present day.

The clouds of historical confusion that hover around the Mountain of Light (Koh-i-Noor’s meaning in the original Persian) began to form before the British acquired it 170 years ago. It was with the coerced transfer of the diamond to Queen Victoria by the 10-year-old Maharajah of Punjab, Duleep Singh, though, that the mythological fog (to paraphrase the authors) was given the “authoritative” (i.e., Western) stamp of the East India Company.

A British civil servant named Theo Metcalfe, who was charged by Lord Dalhousie with establishing an official record of the precious stone’s history to pass on to the Crown, compiled an anecdotal account that he delivered around 1850 and can most generously be described as “good enough for government work.” His none-too-scholarly or careful work deferred to good stories where facts were hard to find.

Use and appreciation of diamonds in India easily date back to 2000 B.C., but the authors make clear that it’s not until the late 1740s that “the first extant, solid, named reference” to the Koh-i-Noor is recorded by a Persian historian. This didn’t stop Metcalfe from establishing a dubious origin story that places the diamond at the center of an ancient theft from a southern Indian temple and then recounts its inheritance through several 14th-century dynasties.

Even as Metcalfe’s history approaches the time of its writing, questionable details are introduced. These include the semi-true story that a Persian warlord obtained the stone from the Mughals (true) by cleverly swapping turbans with their leader, who had attempted to hide it on his head (probably not).

The diamond’s travels in the 100 years leading up to Metcalfe’s report, from India to Persia, on to Afghanistan, and back to the Sikh kingdom in Punjab, are better known and absolutely fascinating even when still hazy. (Was it truly buried in the wall of a prison cell, extorted from hiding only by extended detention and indirect but gruesome threats?)

The older tales are told by William Dalrymple in the first half of the book, as are more ancient stories of India’s rich gemstone culture and evolving aesthetic preferences. When the Koh-i-Noor changes hands and crosses the ocean, Anita Anand seamlessly takes over the narrative.

Anand shares contemporary political struggles for repatriation of the stone (by multiple claimants, including, at one point, the Taliban), as well as the tall tales that continued to accumulate as the Koh-i-Noor traveled to the United Kingdom.

One fun example: John Lawrence, another British civil servant, was (supposedly) entrusted with the stone shortly after its surrender by young Duleep Singh, before its journey to Queen Victoria in 1850. A 19th-century biographer claimed that after Lawrence took the treasure into his care, he casually slipped it into a waistcoat pocket and forgot about it entirely.

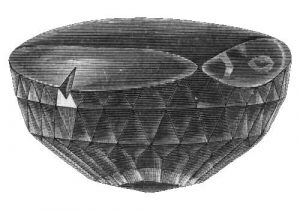

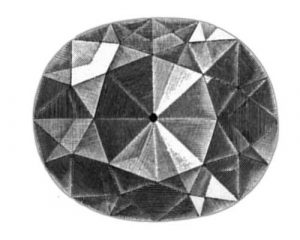

When asked to produce the diamond for transport to the Crown—keep in mind that the Koh-i-Noor was 190.3 cts. before it was cut to a mere 90.3 cts. in England to suit European tastes—he realized the oversight. The careless fellow was only saved from disaster by a thoughtful servant who had kept track of the jewel for him. (Any credulous soul out there like to contact me about a bridge for sale in Brooklyn?)

The Koh-i-Noor at 190.3 cts. before it was transported to England

The Koh-i-Noor at 90.3 cts. after it was cut in 1852 to suit European taste

JCK spoke with the authors about the book and they were emphatic that examining this apocrypha is valuable not simply for its entertainment value, but also because the lure of legend has proved more enduring than the appeal of fact-based research. At the time of the Koh-i-Noor’s publication earlier this year, the Wikipedia entry on the diamond aligned most closely with Theo Metcalfe’s account of the stone’s history.

Anand shared a stunning anecdote about how universally misunderstood the Koh-i-Noor’s history is:

The day that we launched the book I was getting texts from friends of mine who were at the Tower of London, who were still being told that this was a gift from an Indian maharajah to Queen Victoria. Not only that, the Indian Solicitor General…when asked if India was going to make a claim for the Koh-i-Noor…he said, “Of course not, because it was a gift from Maharajah Ranjit Singh to Queen Victoria.” Now Maharajah Ranjit Singh [10-year-old Maharajah Duleep Singh’s late father] had been dead for 10 years [at the time of the transfer], so unless they did it by Ouija board, that didn’t happen.

Dalrymple and Anand, when pressed, wouldn’t share a position on whether the gem should be taken from its home in the Tower of London, but they both expressed a desire for the truth of its history to be better known than it is now. The fact is that the Koh-i-Noor was not (at any time, really) a gift given willingly, but a spoil of conflict taken by a stronger power.

This easily read history of the notorious diamond offers buyers with a taste for adventure many examples of diamond-driven conflict—as the authors don’t hesitate to share—fit for admirers of Game of Thrones. Watchers of PBS’ Victoria or Netflix’s The Crown will also feel at home in the second half of the book.

But for those devoting their lives to this industry, the most compelling parts of Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond may be William Dalrymple’s exploration of the allure held by precious stones for centuries across civilizations. They have been the stuff of myth, as well as of practical tools, prized not only for their rough and uneven beauty—particularly when rubies were more frequently sought out than diamonds in South Asia—but also for their refinement, and (at times) believed to be connected to deities and possess miraculous healing powers.

When balancing authenticity, beauty, and sensuality in enticing young consumers to make diamonds a part of their own stories, one could do much worse than to study the poets in Dalrymple’s early chapters. With apologies for the decidedly male focus on female appearance, rather than accomplishments, 16th-century poet Keshavdas offers these words about the importance of our incomparable wares:

A woman may be noble, she may have good features. She may have a nice complexion, be filled with love, be shapely. But without ornaments, my friend, she is not beautiful. The same goes for poetry.

This may not be a sales pitch to get a millennial interested in an engagement ring, but the poet’s words do speak to jewelry as a deep and enduring source of inspiration. If you care to curl up and recover from last week’s retail rush with 300 pages of history seen through the lens of something you treasure, give Dalrymple and Anand’s book a try.

(Top image courtesy of Bloomsbury; all other images via Wikimedia Commons)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine