Once again, I spent all of last week in New York City, paging through JCK’s back issues—contained in more than 150 Oxford English Dictionary–like volumes currently weighing down the filing cabinets of our office at One World Trade Center in lower Manhattan.

My mission? To identify the vintage covers and ads we’ll be photographing for our 2019 issues, as we gear up for the magazine’s 150th anniversary blowout issue next September.

Beyond sniffling because of all the dust on those ancient pages, managing editor Melissa Bernardo and I marveled at what we found—especially on the covers of issues from the 1960s, which featured a lot of strangely childish illustrations with nary a jewel in sight. If someone had given us a nickel every time we said, “What were they thinking?!”—well, we’d have taken ourselves out for prime rib and martinis.

In all honesty, there was a lot that raised our eyebrows. Dated terminology. Bizarre model choices. Issues bordering on 500 pages! And articles on topics, from man-made diamonds to teens (aka yesteryear’s millennials), that continue to preoccupy our trade all these years later.

One thing that’s impossible to deny when you look through old JCK issues is that for most of its life span, this magazine was kept afloat by the watch business.

Since July 1869, when it was founded by G.B. Miller as the American Horological Journal, a publication devoted to topics such as “watch and chronometer jewelling” and the “new three-pin escapement,” JCK has had deep ties to the watch industry.

Take a look at any issue before the mid-1990s and you’ll see myriad editorials about trends, innovations, and marketing campaigns in the watch business, as well as a staggering amount of advertisements for American watchmakers including Accutron, Bulova, Benrus, Elgin, and Hamilton, but also Swiss brands such as Omega, Rolex, and Vacheron Constantin.

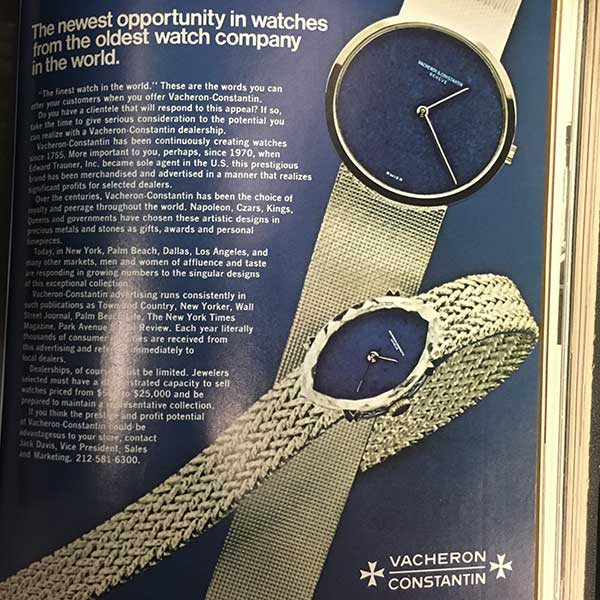

The 1970s were a particularly rich time for watch advertising in JCK—and it’s easy to understand why. The Swiss mechanical watchmaking industry was struggling to find its way in a brave new world inundated with quartz-powered timepieces produced by the upstart watchmakers of Japan. In an effort to convince retailers to support them, the Swiss ran ads touting their prestige and their longevity (case in point: the Vacheron Constantin promo pictured above).

By the time I joined JCK as editor-in-chief in the summer of 2010, however, watch ads had gone the way of the three-pin escapement. That’s because the mechanical watchmaking renaissance that kicked off in the 1990s and exploded in the 2000s pointed brands in the direction of consumer-driven marketing, a phenomenon that continues to this day.

We saw that clearly this past week with Audemars Piguet and Richard Mille, both of which announced they’re leaving the Salon International de la Haute Horlogerie, a Geneva trade show, after 2019 because, in the latter’s case, “the brand’s presence at exhibitions no longer corresponds to its strategy for exclusive and selective distribution.”

High-end watchmakers have been pulling away from the trade for decades, but the phenomenon went ballistic over the past five to seven years. Today, brands are continuously fine-tuning strategies to master retail with mono-brand boutiques, brand-centric lounges, and consumer-facing events such as Watches & Wonders Miami.

But from the vantage point of 150 years, defined largely by a symbiotic relationship between the trade and watchmakers, it’s hard not to see these go-it-alone efforts as risky, misguided, and, yes, arrogant. After all, what happens if there’s another downturn and luxury makers discover that they need their advocates in the multi-brand retail community to ride out the storm? Those onetime advocates might be long gone. And who would blame them?

Top: A Vacheron Constantin ad in the March 1973 issue of Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine