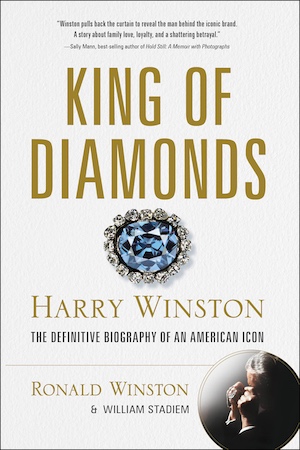

Ronald Winston admits he sometimes got emotional as he researched the life of his famed father for his new book, King of Diamonds: Harry Winston, the Definitive Biography of an American Icon.

In the book—which can be preordered prior to its publication by Skyhorse this fall—Winston, 82, charts his father’s remarkable climb to the top, as well as the tumultuous three decades Ronald headed the company following Harry’s death in 1978.

Winston talked with JCK about what made his father so special, the family feud that almost killed the company, and his memories of Donald Trump, Ross Perot, and Jonas Savimbi.

Why did you write this book?

My father and I were very close. I admired him, both as the “king of diamonds” and also as my father. There are things that I knew, that only I knew, and I decided to write the book for my family. It took a long time, about 10 years.

Your father became such a legend. Is there anything that you think set him apart from other dealers?

He had a vision. They didn’t cut big diamonds back in the 1920s. They cut stones as melee, but not big diamonds. There weren’t many around. What he was doing was different and revelatory.

Did he always know that he was going to accomplish something huge?

He knew he was going somewhere, and he got there. As I write in the book, as a child, he was so poor, he wanted his glass of milk filled to the tippy tippy top, because that was his only luxury.

But he always had an inherent ability. When he was a little boy, he spotted an emerald [in a pawnshop window] that was selling for 25 cents. He bought it, and it was worth $800. The store didn’t realize it was a Colombian emerald. He had an inherent knack for seeing quality and color.

Though his name was famous, your father was low-profile. He was never photographed.

He was a simple guy. He didn’t really publicize himself. He let the diamonds and the jewels speak for themselves.

So how did he become so well known?

He used the press. He made stories, which got headlines. He had a sense of the dramatic: He cleaved a big diamond in public, and mailed [the Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian], rather than have it carried by guards. That all made news, and people didn’t do those kind of things in those days.

JCK just talked with Jeffrey Post, the retiring gem curator of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, about the Hope and its supposed “curse.” Your father owned the Hope for years, before donating it to the museum. What did he think of the talk of a curse?

[Cartier] created that story to interest [socialite] Evalyn Walsh McLean, because she was kind of a quirky lady, so her husband bought it for her. She just loved to do weird things. She would put the Hope Diamond on her favorite Labrador and let the dog wander around the cocktail parties with millions of dollars around his neck.

When my father bought her estate back in 1948, I remember hearing on the radio down in Palm Beach that this socialite had sold her collection to Harry Winston. That was the first time I knew, at age 7, that my father was famous.

Your father was both a retailer and wholesaler, yet the wholesale business was largely kept quiet.

Most people didn’t know [he was a major wholesaler], and my father didn’t want people to know that. He would buy run-of-mine rough from De Beers. He kept the gemstones and sold the run-of-mines stuff to J.C. Penney and stores like that. So he supplied a good part of the American market with his output.

At one point he had a falling-out with De Beers.

They cut him off. He was getting diamonds [as a sightholder] every six weeks, and they thought he was getting too big. They weren’t very nice. It was all about power. He found other sources in Africa, but it was a hardship.

When you took over the business, was it hard following such a legend?

Everyone thought: I was the wealthy son, born with a silver spoon in my mouth, let’s watch him fail.

I remember once, the market was going crazy for big stones. You would buy a big stone on Sunday, and then sell it on Shabbos evening. I said, “This is no good. We’re going to sell all the big stones we have.” My team said, “You can’t do that. You have to show everybody how strong you are.” And I said, “This is what we’re going to do.” I sold every big diamond, and within five or six months there was a tremendous crash, starting in Israel. We bought them back for half the cost.

In the book, you tell a crazy story about meeting [former UNITA head] Jonas Savimbi in Angola.

I had a rule that I would never send people to a place I would never go myself. I knew Savimbi—he was a very intelligent and charismatic guy and warrior. He was heavily guarded in the bush in Angola. It was exciting. I wouldn’t do that today, as a father.

I was very nearly murdered by one of the people who was supposed to guard me—Clark, who was an ex-CIA guy and a soldier of fortune. He saw all this money in cash and diamonds, and he plotted to kill me. My team warned me not to go with him. So I took him to the restaurant at the hotel we were staying at in Switzerland, and said, “We’re not going.” And he said, “What? You can’t do that to me!” He was being paid no matter what, so one less trip to Africa, he should have been happy. So something was really amiss. I didn’t go, and that probably saved my life.

When you were head of the store, you met a lot of very prominent people.

Ross Perot was a client of ours. I remember one of my salespeople told him that a pair of emeralds is the greatest pair of emeralds ever in the history of the world. So Ross called me: [in Texas twang] “I was told these are the finest emeralds on Earth. Are they?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Well, give me a letter.” And I said, “I can’t.” He said, “Why?’

“Because I don’t know what the good Lord is going to make the earth give up tomorrow. But I’m saying they’re the finest I’ve seen.” That was enough for him. He purchased them, but I had to keep one step ahead of my salespeople. They tended to exaggerate, and they got stuck on their own promises.

I knew Donald Trump. I was his first tenant. We used to have dinner. I loaned jewels to his second wife for their wedding. He was egotistical, let’s just say that. Very much out for himself. I wish him well, but I won’t vote for him, and I’m a Republican.

In the 1990s, you ended up in a legal battle with your brother Bruce.

My brother trusted people he shouldn’t have trusted. His lawyer told them that I was the biggest thief ever. That’s never been my nature. I’ve always been scrupulously honest. Why would I steal? I have lots of money. He said to me once, “You want to work. I just want the money.” I said, “Well, how do you think you get money?”

Did you reconcile with Bruce before he passed away in 2021?

No, we never reconciled.

[Diamond miner] Aber bought Harry Winston in 2004. At the time it was an interesting model, a miner buying a retailer. But in the book, you say it didn’t work out.

No. I didn’t get along with [former Aber CEO] Bob Gannicott. He was not suited for the luxury business. When he invited me up to the mine in Yellowknife, he wouldn’t show me any production. That didn’t make sense; I was his partner.

The sale [of the business] happened because of the state of war that my brother declared on me. The judge in the Westchester court had ordered me to sell the company. I either had to buy it myself—and go heavily into debt, which I didn’t want to do—or create an auction. And Aber came in, and they got control. Eventually, they sold it to Swatch.

Have you been involved with the company since it was sold?

Swatch has never talked to me. They have written me out of the equation; I don’t exist. They don’t mention me. It’s Harry, and then Swatch. Which wasn’t what happened at all. I put the company into the watch business, which ended up making a lot of money.

You have been out of the business for over a decade. Do you miss it?

I miss the creative element of finding rare, extraordinary things. I miss working on press and advertising. So yes, I do miss it.

What would you want people to know about your father?

He was an extraordinary personality. He was brilliant, and also very kind and generous. He created charities and gave the Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian.

In your book, you write about being more interested in science than in jewelry. Do you regret taking over the company?

No, because it gave me a chance to start a foundation, and right now we’re working on a cure for cancer. We’re very close. It’s based on a new molecule, which is based on penicillin, believe it or not. Everything worked out. I was able to save the business, make it bigger, and at the same time do my science.

(Top photo by Monarch Photography; photos courtesy of Ronald Winston)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine