When Krista Knickerbocker was an architect working in the Boston area, she was a part of a wide array of design projects that felt intellectually stimulating, including an aquarium and a science center in Saudi Arabia.

Exciting? Yes. Limiting? Also yes. Sure, the Saudi Arabia projects were important professionally, Knickerbocker says. But no one was putting her on an airplane to experience her work in person.

“I knew I would never get to see them, and it felt so distant and abstract,” Knickerbocker says. “I worked on some smaller scale, more local design projects as well, but again I felt like my entire life was dictated by the schedule of the projects I was working on. At this point, I had a baby at home, and I couldn’t figure out in this deadline-driven world of early mornings and weekends at your desk how I could bring that career into the future that I really wanted for our family.”

Somewhere around this time, her husband’s wedding band needed a fix. The band was a mix of metal and concrete, and the concrete inlay had eroded. This is where inspiration met Knickerbocker’s unique background—not only did she make architectural models in grad school out of a fine-grain anchoring concrete, but she also had a DIY mentality set in place by her physical therapist mom and entrepreneurial dad back in Winchester, Mass.

“Going back to the theme that I grew up with of just learn how to fix it yourself, I went to the local hardware store and purchased a small bag of concrete to fix the ring. Since I had the whole bag left over, it felt like an invitation to make more with it,” Knickerbocker says. “At work at the time, I had access to a 3D printer, so I started 3D-printing pendant and earring designs that I would use to make a silicone mold with and pour the concrete to create my first pieces of jewelry that I sold.”

Knickerbocker did what any rational person does next—she opened an Etsy shop and started making jewelry. And, like every person who gets into jewelry, Knickerbocker got obsessed. Concrete led to lost wax casting. That led to online and in-person classes. That led to starting Krista Knickerbocker Designs, a jewelry business that gives this mom of three a way to focus on family while still using her time, talent, and skills in a substantiative way.

“I finally feel that I’m building a jewelry business that I’m proud of, and I feel every day like I’ve finally found my medium as an artist and designer,” Knickerbocker says.

Knickerbocker never expected to work in jewelry. She is the second of five kids, and life was hectic. Her dad also worked as a residential contractor and had a local indoor sports facility at one point, so Knickerbocker always had something to do with a sibling or an after-school job.

“I actually didn’t take freshman art until my senior year, and that was because it was a state requirement to graduate. I loved it, though, and went on to minor in studio art in college to make up for lost time,” Knickerbocker says. “I always felt like I knew I was an artist, but I just didn’t know what my medium was.”

During her college years, Knickerbocker added an economics degree from Boston College and an internship at an investment banking firm—which taught her what she did not want to do, she says. She got her master’s degree in architecture from Washington University in St. Louis and fell in love.

“The rigor of the education, the studio culture, the creativity that it pulled out of us, the material explorations that we did—it was really an amazing few years. It was constant and demanding, and I spent many nights in the studio developing designs and preparing for critiques, but it was so valuable,” Knickerbocker says.

“Architecture as a profession can be very specific, and you can end up working on one type of project and in one way for your entire career. As an education, though, architecture is really broad and endless. It was rooted in design thinking, prototyping, iterating, and constantly acquiring new skills and techniques,” Knickerbocker says. “It really taught me to be unafraid of learning new skill sets that I may know nothing about, which has benefited me so much in my jewelry journey.”

Now, her jewelry work is textural, handmade, and organic—a balance between “imperfect, often porous forms that are created from something permanent and usually precise, like metal,” Knickerbocker says. While her architectural life likely isn’t over, the jewelry part of her life is just as meaningful.

“In general, I love the scale of jewelry, I love how meaningful it is to people. I love its potential to be symbolic, to carry memories of a person or a place, to become a part of someone’s identity, and to make people feel a little more confident as they go out into the world each day.

“I also love the ability to iterate on pieces and to find inspiration everywhere,” Knickerbocker says. “After working in architecture, where time lines felt glacial with projects going on at times for years, having the ability to make a piece in a week or a day or an hour is magical.”

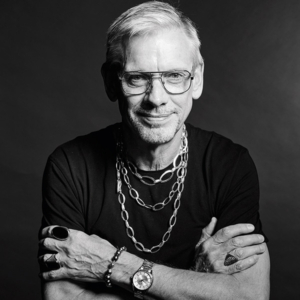

Top: Jewelry designer Krista Knickerbocker has moved from banking to architecture to jewelry, learning along the way that what she values as much as education is time, craft, and a connection to her work (photos courtesy of Krista Knickerbocker Designs/photographer Emily Elyse of Rose and Julep).

Follow me on Instagram and Twitter

Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazineFollow JCK on Twitter: @jckmagazine

Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine