As someone who finds history, especially when it comes to decorative arts, compelling, I was excited to learn about the publication of The Elements of a Home: Curious Histories Behind Everyday Household Objects, from Pillows to Forks (Chronicle Books, $19.95). The book, which will be released on Tuesday, is the work of Amy Azzarito, a design scholar and historian who holds master’s degrees in both the history of decorative arts and design and library science, and has lectured extensively at universities and historical societies across the county.

She’s also a good friend of mine, whose professional accomplishments and personal style (and exquisite Russian Blue cats—hope they are still with us?) I have long admired. When I knew her in New York (she’s in Northern California now), Azzarito worked for five years as managing editor at Design*Sponge, where she penned a column on design history. She also worked for eight years as a librarian at the New York Public Library.

The book sheds light on the secret histories of more than 60 commonplace household objects—I didn’t know if there would be anything jewelry-related in it and—yippee!—there is an entire section devoted to the jewelry box/armoire.

Below is the excerpt in full. Maybe the factoids contained herein can be layered into conversations with customers? I can’t be the only jewelry lover who finds this stuff fascinating!

Jewelry Box

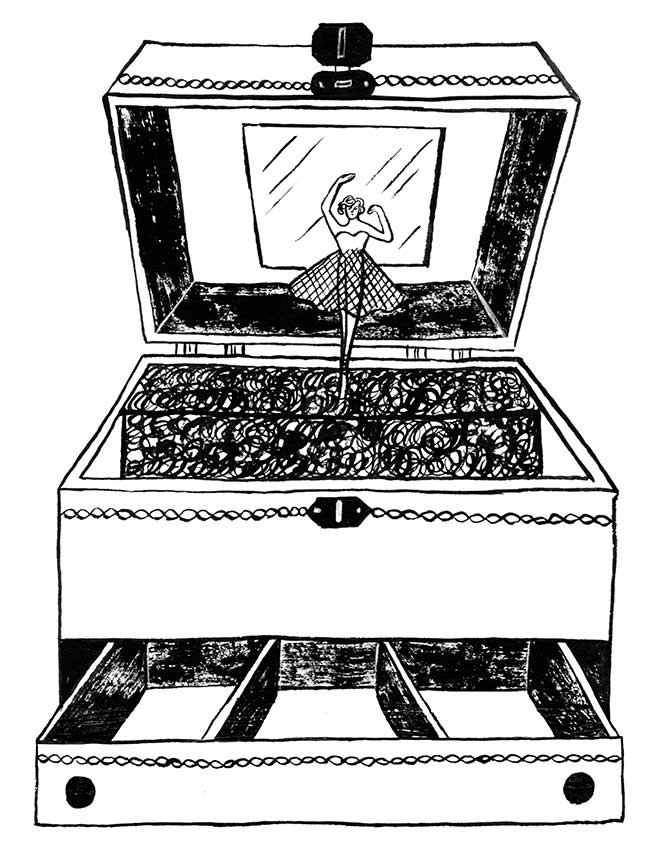

Is there anything more charming than a velvet-lined box filled with glittering baubles? From ones that play a tune to the iconic blue of Tiffany’s leather version, a jewelry box is one of the few decorative objects that nearly all women have in common.

The jewelry box most likely came to be as soon as there were jewels to put inside. But let’s pick up the story in the Middle Ages. Before safes and safe deposit boxes (or even locks for doors), home security was of utmost concern, and at the time, iron was the most theft-proof material for protecting valuables. Unfortunately, it wasn’t the most practical option if you needed to move. Because portability was essential to the medieval lifestyle, most boxes for safekeeping were made of wood, covered with leather, and bound with iron for a little extra security.

During this period, a groom would often gift his betrothed a jewelry box filled with jewels (or perhaps empty with promises of gems to come). To emphasize the point of the box, the leather might be embossed with appropriate inscriptions and scenes of courtship. A favorite choice was a quotation from the stories of Chrétien de Troyes, the twelfth-century poet: “Lady, you carry the key / and have the casket in which my happiness / is locked.”

A prospective bridegroom could buy boxes with empty crests that could, post-purchase, be hand-painted with his own.

The custom of presenting a lady with a jewelry box on her engagement continued into the Renaissance. In Florence, the trend was to use a rectangular musk-scented box, decorated with gold-leafed hunting scenes. A wounded stag symbolized carnal passion, so it was a gift with a little extra vroom-vroom.

Renaissance women didn’t necessarily wait for a man to provide the jewelry (or the box!). Many women had boxes that hung on the wall in their bedroom next to a small mirror. A foot high, it would contain a smaller box for jewels as well as other items necessary to a lady’s toilette: makeup, powders, sponges, and pins.

During the eighteenth century, bigger was better. As a wedding gift, Louis XVI presented Marie-Antoinette with a jewelry box the size of a small table.

Made of tulipwood, it was balanced on delicately curving cabriole legs, embellished with floral porcelain plaques, and hand-painted with flowers. But even a table-size jewelry box wasn’t enough to hold the jewels of the future queen of France. By tradition, the French royal family presented the new bride with all the jewels of past queens—like a pair of diamond bracelets that cost as much as a Paris mansion. To accommodate the treasures, Marie-Antoinette ordered a massive “diamond cabinet.” Eight and a half feet high and 6 feet wide, with mother-of-pearl, sea green marble, and gilt detailing, the cabinet was as sparkly outside as the jewels within.

Marie-Antoinette had her cabinet, and Mexican women had their secretas. These low, square boxes on round bun feet were decorated with turtle shell, bone, and mirrors inlaid in geometric patterns. Although they were beautiful enough to be displayed, they were often stowed under beds or hidden in secret cubbyholes for protection from theft.

And it wasn’t only the ladies who had elaborate storage for their baubles; young men were also dazzled by a little sparkle. After a stint in Europe to add a bit of continental polish to his education, the Scottish Duke of Atholl commissioned a small box in the shape of the Roman temple Septimius. Constructed to split open halfway to reveal tiny trays, the box housed the duke’s collection of coins and medals. His favorite post-dinner activity was showing off the collection; the box was part of the show. With his elaborate jewelry box, the duke was taking a page from the lineage of the most dazzling of kings, the French Louis. Louis XV had a jewelry box that was large enough to be called a cabinet with blue velvet– lined drawers to store a numismatic collection that celebrated the great events of his reign. His grandson, Louis XVI, had an astonishing medallion decorated mahogany version that rivaled the one owned by his wife, Marie-Antoinette, for size and decoration.

Each medallion was made of wax, feathers, and wings arranged to look like birds, butterflies, and plants. In 1796, an invention by Swiss watchmaker Antoine Favre added another dimension to jewelry boxes. Favre had already developed a tuned-steel comb that made previously bulky music boxes portable and pocket size. It was incorporated into jewelry boxes in the nineteenth century. To further entice shoppers with money to spend, mechanical figurines—like a pirouetting ballerina or a singing bird— were added to move when the box’s lid was opened.

The sales of jewelry boxes, both musical and silent, declined during World War I, when ostentation was frowned upon. Then in the 1920s, Coco Chanel made costume jewelry fashionable, and a golden age of affordable adornment began. A jewelry wardrobe was in reach of every woman, and remains so today.

If diamonds (real or faux) are a girl’s best friend, then doesn’t she need a place to keep them?

(Reprinted from Elements of a Home by Amy Azzarito with permission by Chronicle Books, 2020)

Top: A velvet-lined jewelry box that author Amy Azzarito discusses in her new book Elements of a Home: Curious Histories Behind Everyday Household Objects, from Pillows to Forks (Chronicle Books, $19.95). Image via: picspree.com.

Follow me on Instagram: @aelliott718

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine