While many had hoped the G7 ban on Russian polished diamonds would take effect on Jan. 1, 2024, it will probably start next March at the earliest, sources involved in talks on planning the ban tell JCK.

G7 representatives working on the issue have said they intend to finalize a proposal by mid-November. Then they will send it to their respective governments, which may decide to modify it, either on their own or in tandem with other G7 countries. (The G7 is a forum for members to coordinate policy but has no power to enforce anything it recommends.)

The ban is expected to initially affect diamonds 1 carat and larger. The European Union, including Belgium, may stop importing Russian rough before it takes effect.

Coming up with a G7 plan has taken longer than expected—the original target date for a proposal was May—in part because officials have had extensive consultations with industry, including a recent visit to India.

“We are grateful for the opportunity that you have given us and the diamond industry to engage with you regarding the framework of import requirements for diamonds,” wrote De Beers CEO Al Cook in an open letter to G7 leaders published yesterday. “Throughout our discussions two things have been clear—why we should do this is easy, but how we should do it is hard.”

It’s proved so hard that even the trade can’t agree on a solution.

The Belgian government, working with Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC), has submitted a plan for a Russian diamond ban. Three industry groups have also submitted proposals: the World Diamond Council (WDC); the French jewelry association UFBJOP; and India’s Gem & Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC), in conjunction with that country’s government.

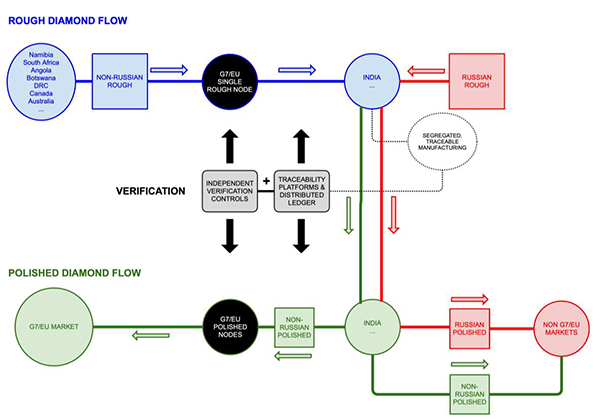

Most of the plans rely on technology-based tracking services—such as Tracr, Sarine’s Diamond Journey, and Everledger—that will require information be recorded on a “distributed ledger.” One challenge is finding a way for all the systems to “talk” to one another, the same way SWIFT serves as online clearinghouse for financial transactions.

In addition, there’s growing doubt these systems can handle the large number of diamonds that will have to be tracked.

“De Beers has developed the world’s leading diamonds blockchain, Tracr, but even we recognize that no single technology-based platform is capable today of meeting the G7 requirements,” Cook wrote in his letter. “In the near-term, technology can support a framework, but it cannot be the framework.”

UFBJOP made a similar point in its proposal: “These technologies are not mature enough today to support…the entire value chain and could potentially open the door to contamination with Russian diamonds.” The association called for a “third-party evaluation” to test their reliability.

Use of the tracking services raises another issue: Previously confidential information could be made be available on a possibly open document. UFBJOP warned there is a “need for a strong and neutral cross-industry governance around a potential public ledger.”

It will likely cost companies around $20 to $30 per diamond to comply with the Belgium-backed plan, Kilian De Saeger, a policy official with Belgium’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, told members of the U.S. industry on a conference call last week. Industry personnel on the call found that number high.

Belgium’s plan would route most diamond production through polished and rough “nodes” that would be located—at least initially—in Antwerp, though it’s possible G7 member Canada could have a node for rough near its mines. UFBJOP warned this could create a “bottleneck” and might not be compliant with international free trade agreements.

At the recent CIBJO Congress in Jaipur, India, WDC president Feriel Zerouki said her group’s G7 diamond protocol “does not favor one center over another” and is “equitable to all” as it would not bar “artisanal and small-scale miners, as well as members of [India’s] cottage industry and trade.”

The WDC plan calls for companies to declare on their import notices that their shipments contain no Russian diamonds; those assertions would then be audited by local trade associations. Some in the business worry that such audits could expose confidential information to competitors; others say industry self-governance won’t provide necessary assurances.

UFBJOP’s plan allows for supplier declarations, which would subsequently be backed up by a “robust quality assurance system,” to be gradually phased in. Like Belgium’s plan, the French one wouldn’t allow parcels of “mixed” origin. (Belgium makes an exception for De Beers’ “Botswana sort,” while UFBJOP’s does not.)

Under India’s proposal, a new GEMPACT system to ensure compliance with the ban would be established, administered by the GJPEC and monitored by India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry. The G7 is invited to set up an office in Surat or Mumbai to gauge how well GEMPACT works, the plan says.

(Top photo by Getty Images)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine