A few weeks ago, I had the pleasure of visiting London as a guest of Forevermark, the ethically sourced loose diamond brand founded by the miner in 2008 to promote its finest stones. Over the course of three days, I joined the brand’s second annual Carat Club excursion, a perk for salespeople who’ve sold 35 or more 1 ct.–plus Forevermark diamonds in a one-year period. (The 2016 class flew to De Beers’ Victor Mine in Canada.)

On day one, our group of 17 toured De Beers’ International Institute of Diamond Grading & Research (IIDGR) in Maidenhead, located about an hour west of central London (followed by a tour of Windsor Castle!). On day two, we sat down with Forevermark CEO Stephen Lussier at De Beers headquarters (followed by a private tour of the crown jewels and an über-exclusive dinner in the Tower of London). And on day three, we flew to Antwerp (and back) to tour the IIDGR’s larger Belgian facility.

Our group of 17 at De Beers headquarters (photo by Nicholas Andrews Photography)

The trip afforded me an excellent fly-on-the-wall opportunity to witness how Forevermark trains and rewards its top sellers. Here are five surprising bits of insider knowledge that I came away with:

RFID technology makes the Forevermark Diamond Institute go round.

The Forevermark Diamond Institute sits under the umbrella of the IIDGR, which was established by the De Beers Group of Companies in 2008 to provide verification instruments and diamond grading services to the jewelry industry. With two big locations in Antwerp, Belgium, and Surat, India—each handling between 200,000 and 300,000 cut-and-polished diamonds per year—and a smaller facility in Maidenhead, the IIDGR receives diamonds from diamantaires all over the world, and puts them through a rigorous, high-tech process to determine if they’re fit to be inscribed with the Forevermark logo. That determination comes down to a team of experts and a meticulous screening process.

Simply keeping track of the influx of stones requires a sophisticated scanning and tracking system powered by RFID technology. Every single diamond is shuttled around the lab in its own box, which bears a unique RFID tag, allowing Forevermark to keep track of its whereabouts—and the employee responsible for it at every stage of the way. (One thing to keep in mind is that the box is metaphorically black, meaning its owner and origin are unknown.)

Each diamond passes through roughly 37 steps before it’s declared a Forevermark stone. The first task involves weighing the diamond: Forevermark measures the carat weight down to six decimal points, as opposed to the industry standard of two. The next step relies on a Sarine machine to determine polish proportions and build a 3-D model of the diamond. In step three, an in-house color grading machine named Falcon takes over, and within five seconds, determines the stone’s color grade, including numerical subgrades used strictly in-house.

(Fun fact: The lab has a thing for naming its grading machines after birds; the quality grading machine is called Eagle.)

Although machines do much of the heavy lifting during the grading process, the lab’s employees manually grade each diamond, after which the human and machine data is matched. Maidenhead, the “baby lab” compared to the bigger Antwerp and Surat facilities, employs eight graders, who grade every diamond blind, meaning they can’t see the grade determined by the machines. Anything lower than an 82.5 percent spot-check agreement rate between the human and the machines suggests the former requires more training.

Forevermark recently inscribed its 2 millionth diamond.

In Antwerp, I picked up a July 2017 issue of De Beers’ in-house Pursuit magazine (it’s actually more like a really well-produced pamphlet) and it contained an interesting fact: Forevermark recently inscribed its 2 millionth diamond, a gem mined, cut, and polished in Namibia.

As part of the tour at Maidenhead, we witnessed the inscription process. Once a graded diamond has passed Forevermark’s muster—a Forevermark diamond must be completely natural and must have close to a perfectly polished table, where the inscription is placed—it is mounted for inscription. The process is far more elaborate than I would have guessed and includes cleaning the surface of the stone in acetone, projecting the Forevermark logo, checking that it’s placed correctly, and then doing it all again three times before the mark is permanently inscribed.

De Beers’ unofficial mantra? No synthetic left behind.

Many people don’t realize that De Beers has been in the synthetic diamond business longer than just about everybody. The group’s Element Six subsidiary was founded by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer in 1946 to focus on the market for industrial diamonds, and it began producing synthetics in commercial volumes in 1960.

Today, the researchers at De Beers Technologies UK (based in Maidenhead) work closely with their counterparts at Element Six to identify emerging lab-grown technologies. Samantha Sibley, a technical educator with De Beers, talked our group through the various screening and detection machines they now sell to the industry at large—everything from the compact screening device known as DiamondSure to the $45,000 AMS machine, which is intended for parcels of melee and can accommodate up to 500 cts. at a time, and to the more sophisticated DiamondView, which is designed to take any stones referred by either of the two other machines for additional testing.

“Consumer desire is the only source of value for our business.” That sentence appeared in a video we saw at De Beers headquarters. There’s no question in my mind that the researchers at IIDGR can detect any synthetic diamond that tries to pass, undetected, through their midst. But given the plummeting price of HPHT presses and the existence of large lab-grown producers in China and Russia, such as New Diamond Technologies in St. Petersburg, I have to wonder what’s happening to diamonds that don’t pass through the IIDGR’s facilities. Are manufacturers and retailers prepared to invest in the screening equipment that will help them identify lab-gown stones mixed with naturals? From De Beers’ perspective, that’s (quite literally) the $64 billion question.

Selling Forevermark still comes down to sparkle.

Cory Schifter of Casale Jewelers in Staten Island, N.Y., was one of the Forevermark retailers on the trip. When I asked him if all the technical mumbo jumbo we’d learned would help him sell more diamonds, he said his sales strategy is to let the diamonds speak for themselves.

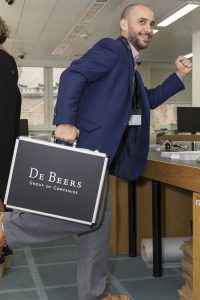

Cory Schifter of Casale Jewelers in Staten Island, N.Y., at De Beers headquarters (photo by Nicholas Andrews Photography)

“It sparkles like no other,” he said. When a client picks a Forevermark diamond out of a lineup of generic stones, he’ll jump on it. “You just picked a diamond that’s been handpicked by Forevermark,” he’ll say. “At that point, we’ll tell the story, put the diamond into the viewer, and show them the inscription. They’re wowed by it. They start to relate to the numbers in the inscription, like maybe they’ll recognize their anniversary date in the number, or her birthday, or their social security number. Most people will find something.”

Schifter told me he likes to explain the journey the diamond has taken from the mine all the way to his store, and then on to someone’s family. “A lot of guys latch on to that,” he said. “It’s easy once you believe.”

Carat Club membership comes with serious perks.

If you are a Forevermark retailer—or aspire to be one—know that when you join the ranks of its top salespeople, you open yourself up to some pretty stellar opportunities. Like a private tour of the crown jewels followed by a private dinner at the Tower of London, capped by an exclusive viewing of the tower’s 700-year-old Ceremony of the Keys. It’s been weeks and I’m still processing the awesomeness of the experience.

The Tower of London (photo by Nicholas Andrews Photography)

We weren’t allowed to take photos inside the tower where the jewels are displayed. But given that a slow day sees 8,000 people on the tour and on a peak summer day that figure is closer to 17,000, being one of a group of 17 was like winning the tour-group lottery. The dinner that followed—in the Wakefield Tower, one of the oldest parts of the medieval palace (built in 1220)—was another revelation. There, amidst the ghosts of Tudors and Windsors past, beneath a vaulted ceiling, steps away from the exact spot where King Henry III died in 1471, I feasted on braised beef and potatoes washed down with copious amounts of red wine. I’m not rich, but that doesn’t really matter because this experience isn’t available to just anyone with money. It’s for people with access. And thanks to Forevermark’s largesse, for a brief moment, I was one of them.

Dinner in the Wakefield Tower with Forevermark’s Jeff Skaret and Kristen Lawler-Trustey, The Adventurine’s Marion Fasel, and April Busby of Bere’ Jewelers in Pensacola, Fla. (photo by Nicholas Andrews Photography)

(Top: photo by Nicholas Andrews Photography)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine