Copyright infringement in the jewelry industry appears to be on the rise, thanks to numerous factors, not the least of which is Instagram. Not only has the platform allowed copycats to thrive, it has also been the source of their undoing. JCK explores the intersection of design, imitation, and cancel culture.

Marla Aaron has seen so many copies of her jewelry designs over the years, she’s developed a thick skin when it comes to knockoffs.

Still, the New York City–based jeweler smarts a little when she sees a designer she considers a peer hijack one of her original ideas. Which is what Aaron alleges happened when fellow New York City brand Aurate debuted a collection called Lioness, in collaboration with actress Kerry Washington, in November.

The collection, modeled by Washington in Instagram posts and on the brand’s website, included a chunky vermeil carabiner, which Aaron says the brand copied “implicitly and completely.” Dozens of her fans and supporters agreed with her, and an Instagram pillorying ensued, with Aaron’s supporters flooding Aurate’s feed with comments chastising the young brand for allegedly co-opting a proprietary design. (Aurate quickly deleted the comments.)

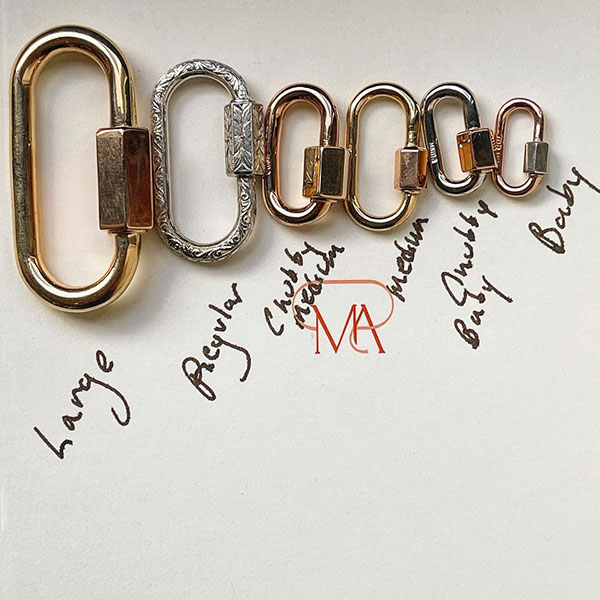

Days later, Aaron sent a letter to the brand’s founders, Sophie Kahn and Bouchra Ezzahraoui, in which she acknowledged that she didn’t invent the jeweled carabiner (Bulgari and Tiffany & Co. have made jewelry carabiners for keychains), but insists her brand established the hardware store staple as a standalone piece in fine jewelry. “The morphing of the sizes, putting a fine jewelry spin on it—we own that,” she says.

At press time, Aaron has not filed suit against the company. And Kahn and Ezzahraoui denied the allegation in an email to JCK. “At Aurate we celebrate women, and women-owned businesses, in every way that we can—it’s our moral code,” they wrote. “As a company born out of both originality and integrity, we can guarantee there has never been any form of plagiarism of design, whether with respect to this specific collection or any other in the history of the company.”

The Cost of Doing Business?

The situation was uncommonly public, but not at all uncommon. Allegations and cases of intellectual property infringement have long plagued the jewelry industry. But many in the trade have noticed an upswing in copycats in the last few years.

Alison Chemla, founder of New York City–based Alison Lou, thinks Instagram could be at the root of the problem. The platform “has made it really easy nowadays to copy people,” she says. Chemla’s own Emoticore collection, which introduced emoji motifs into fine jewelry, was copied mercilessly after its 2012 debut.

Fine jewelry’s growing popularity also makes it a popular target for pirates. After playing a supporting role to apparel for decades, designer fine jewelry is now as coveted—and copied—as designer dresses, shoes, and handbags. And the fact that fine jewelry is a “forever” purchase resonates with the growing ranks of consumers who prioritize sustainability and like the idea of buying products destined to become heirlooms.

Retail sales of fine jewelry throughout the pandemic illustrate this shift. During the darkest days of the crisis, we traded our dresses and heels for Old Navy sweatpants, but spent our travel money on sentimental and enduring items, such as fine jewels. Unscrupulous makers and manufacturers are aware of this and know there’s lots of money to be made in selling people exactly what they want—down to the prongs of a sapphire’s setting—for less.

The most shameless infringers are called out by the hoards on Instagram, arguably ground zero of our so-called “cancel culture”—the social media–fueled practice of ostracizing companies or people that have done something considered offensive or objectionable.

Here’s how that typically happens: Instagram feeds such as Diet Prada—the once-anonymous account founded by fashion pros Tony Liu and Lindsey Schuyler in 2014 to draw attention to design theft in the fashion industry—are joined in decrying imitators by a chorus of rubberneckers: brand loyalists, thought leaders, publicists, influencers, celebrities, and plenty of people swinging by simply to marinate in the drama. Outraged comments abound, and screenshots of the alleged copies, often shown side by side with the original design, ricochet around the internet. The company or brand is publicly shamed or “canceled.”

But these takedowns aren’t necessarily arrows to the heart. Plenty of brands survive cancellation and go on to copy again. Cancel culture draws attention to the crimes of intellectual property infringement, but it may not be an effective deterrent, at least on its own.

And yet the legal avenues available to jewelry designers who’ve been victimized are just as unreliable. As a result, many designers view copycatting as an unavoidable, albeit unsavory, price of doing business.

Chemla recently debuted her first bridal collection, I Do by Lou, and was careful to obscure design details in photos and tightly control the images she sent to media outlets, all to counter imitators. “It’s something we really discussed before the launch,” she recalls. “How do you showcase the jewelry and also protect the design? Now I’m so paranoid and nervous about showing my work in advance. What if someone has faster manufacturing than I do?”

Like Aaron and a handful of other designers who have originated ideas that went on to become major jewelry trends, Chemla has filed copyrights and patents for certain designs and design elements. But she became exhausted chasing down copycats in the early years and is now picky about whom she pursues.

“When I started, it would get me so upset,” she says. “But there came a time when I had to put my blinders on and make new pieces and move forward.”

Legal Unease

Many attorneys would say there’s no clear-cut way to safeguard a jewelry design. Intellectual property law, the legal area that deals in copyrights, patents, and trademarks, has its own processes, precedents, and particularities. But in practice, a high degree of subjectivity undergirds most court decisions in infringement suits. The burden to prove that a work has been copied rests on the accuser, and the bar to prove infringement is notoriously high.

This is in part because jewelry has been made for thousands of years, and it’s rare that elements or complete designs qualify as “original,” and therefore protectable under intellectual property laws. Ornamental and design aspects of jewelry are deemed original only when they are the sole result of a designer’s creative effort and provide a “distinguishable variation” over prior work pertaining to similar articles. Again, this is challenging to prove.

A designer holds a copyright on a design the minute he or she fixes that design in a “tangible medium,” which simply means turning an idea into an actual ring, pendant, bracelet, or other piece. But there’s a cruel Catch-22: Unless a design is protected by a registration of copyright through the U.S. Copyright Office, an individual can’t legally challenge a copier. And the task of pursuing a copyright or patent (more on patents below) can be prohibitively expensive for an independent designer. Aaron, who holds several patents for her designs, wryly notes, “I could buy a house in the Hamptons for what I’ve spent filing patents.”

Compounding these hurdles, the U.S. Copyright Office has recently narrowed its parameters when it comes to what can be copyrighted in jewelry, says Tiffany Stevens, CEO and general counsel for the Jewelers Vigilance Committee.

“We’ve seen that their standards have changed in the last two years for jewelry, and we don’t know why that is,” Stevens says. “You want there to be the opportunity for things to be wide open and for competition to [flourish]. But we think jewelry design should be more copyrightable.

“My personal opinion is that they think of jewelry as women’s work,” Stevens adds. “Think about it—jewelry, recipes, crafts. They are all considered community property, and they’re basically uncopyrightable. Meanwhile, men’s ideas are fiercely protected.”

David Kerr, an intellectual property attorney based in Boulder, Colo., who works with fine jewelry designers and manufacturers, says many jewelers are stymied by the obstacles inherent to bringing legal challenges. “Oftentimes the ability to enforce your rights just becomes so difficult, the majority of people throw up their hands and say it’s not worth the costs,” he says.

With the rise of online marketplace Etsy, social commerce, and direct-to-consumer selling, the barriers to entry for jewelry entrepreneurs are so low that “anyone can start offering their jewelry on their Etsy site right away,” Kerr says. “They can have copies made overseas and prototypes rapidly done.”

Established jewelry brands such as Tiffany & Co. and Cartier have the resources to go after design thieves. For them, it’s less about recouping sales and more about protecting their rights, Kerr says. But for independent jewelry designers, bringing offenders to justice “becomes so very difficult to enforce,” he says. “It can be done, but you have to have a commitment to it, and it’s going to take up a lot of your time. I’ve seen people trying to put out every fire and shut down every Etsy account, and then realize that they can’t shut down every potential infringement. They eventually reserve enforcement for the most egregious cases.”

That’s the tack jewelry designer Lydia Courteille has adopted after many years of confronting numerous copycats, including a jewelry designer at a revered Parisian fashion house who’s made a decent name for herself in the industry producing slightly tweaked Courteille designs, among other pieces.

“You cannot fight against them all of the time,” Courteille says. “It’s too much energy and too much money.”

Instead, she starts a file when she sees a copy, and after a few copies from the same brand, “I take action.” And in Courteille’s experience, “when you move against someone copying you, you have to prove that it’s a 100% copy or you will lose. If it’s a 90% copy, you will lose. Even with a good lawyer, you will lose your money and time.”

Market Share

Kerr thinks patents, as opposed to copyrights, may be a more accessible way for jewelers to guard their work.

There are two types of patents: utility and design. A utility patent protects the way an article is used and works, while a design patent protects the way an article looks, according to the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Jewelry designs can be eligible for both. The downside of a patent is that it expires after 15 years, while copyrights endure for 120 years from the date the work was created. Considering how quickly trends blow through fashion and jewelry, however, 15 years of legal protection against piracy could be sufficient.

Kerr recently represented a well-known jewelry designer who applied for a utility patent on a system of couplers she’d made that allow wearers to mix and match different elements within the collection. Clasps, hooks, and other jewelry elements that utilize engineering—often to get jewelry on and off, or to reconfigure a jewel—are good candidates for utility patents. Earning a design patent is more difficult, Kerr says, but can be done “if you come up with a very complicated design.”

Fine jewelry designer Eva Zuckerman, founder of the NYC-based Eva Fehren brand, says she had some success in filing both copyrights and patents, but that the minimalism of her work made it hard to find official ways to protect it. Her brilliantly simple X ring has been one of the most copied jewelry designs of the last decade.

The designer says her company files copyright and patent claims when possible. “But we don’t do it across the board because at some point it became too big of a hurdle to climb,” Zuckerman says. “It affected me and my creativity being in this constant battle to own and protect what’s mine. And we didn’t have the resources to fight left, right, and center.”

Zuckerman, Chemla, Courteille, and Aaron send cease-and-desist letters to copycats on occasion, and sometimes see results. “I’ve had people I’ve sent letters to who have no idea they are copying a design that’s already out there,” Chemla says. “It’s clear they literally just picked the design out of a catalog and had it manufactured. Some of them are apologetic.”

Kerr wonders if, instead of relying on the legal system, starting a movement against knockoff artists in the industry might be a more effective way to address the problem. It would need to be a loud movement and one that includes heavy hitters, he says.

“In the absence of a good legal avenue, social pressure to do the right things and operate your business in the right ways can be an effective strategy,” Kerr adds. “You’d have to get people up and down the supply chain, from designers to retailers, to say, ‘We’re not going to deal with companies that make knockoffs. Maybe the copyright law isn’t a great avenue to police this industry, so we’re going to police it ourselves.’”

Designers say store owners have the power to curtail copycat brands—simply by refusing to carry them.

“I do think retailers have a little bit of responsibility here,” Chemla says. “A retailer will take a [knockoff] brand that’s less expensive than mine and put it next to my brand in their store. Once a designer is validated by a retailer, they continue to create knockoffs. They think, I’ve already done this, I can still keep doing it.”

Any potential movement to police piracy in the jewelry industry would need to be built on a foundation of trust between designers and retailers, brands and manufacturers—and would certainly require savvy leadership. “But if you can get enough movement in the industry of people saying enough is enough,” Kerr says, “it just might work.”

Top: Marla Aaron’s Original and Heart Locks