Brands based on artisanal and small-scale mining have become the new frontier of sustainable jewelry. We highlight four notable players in the sector.

The jewelry business has long faced questions about conditions in the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) industry—with good reason. Its miners often work in hazardous conditions, are poorly paid, and sometimes sell to criminals or terrorists. Some mines employ children.

But the sector also has its advocates. They argue that ASM employs tens of millions of people, who work in mining because it pays far better than farming. Advocates compare the Western world’s critique of artisanal miners with the 1990s crusade against sweatshops, which resulted in many former workers of closed factories turning to prostitution to make ends meet.

“There are a lot of people sticking their noses into the artisanal miners’ world,” says photographer Hugh Brown, who specializes in taking photos of small-scale miners. “If you lessen the share of what is mined artisanally, a lot of them are going to lose their jobs. The question is, Where do these people go? What do they do?”

That poor miners could be hurt in the name of sustainability strikes some as particularly ironic.

“I’m afraid of artisanal and small-scale miners being left out of the sustainability conversation,” says Cristina Villegas, director of sustainable markets for Pact, a Washington, D.C.–based antipoverty nongovernmental organization (NGO), and head of its Moyo Gems program. “They are often the most affected by climate change.”

Moyo Gems is one of several jewelry product lines that primarily use materials sourced from the ASM sector. These initiatives, generally sponsored by or connected to nonprofits, have different business models but similar missions: They provide extra resources for the miners and ensure they are working in safe, humane conditions. Even De Beers Group is getting in on the act with GemFair, which sells diamonds mined in co-ops in Sierra Leone.

At best, these products improve the lives of vulnerable people. They could even be called sustainable—a word not generally used about materials that are mined—as they have a positive impact on the environment. Some premiums from sales of Fairmined gold, for instance, go to buy instruments that don’t use mercury. One Swiss Better Gold co-op built a well for its village, reducing carbon emissions (previously, the water was brought in by truck).

Below, we highlight four programs that sellers of fine jewelry should know if they are concerned about the ethics and sustainability of their supply chains.

Fairmined gold

In 2007, the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM) introduced the Fairmined standard, which has since established a reputation as the gold of choice among brands that support sustainability. The initiative pays miners extra money for their labor, in the form of a premium, and exercises tight control over the conditions at its mines. Fairmind gold is used to make Nobel Prize medals and the Cannes film festival’s Palme d’Or award. Jewelry brands like Chopard and Kering use it too.

Yet for all Fairmined’s advocates, two big issues have kept it from wider acceptance. One is the cost, which is significantly more than regular gold because Fairmined gold is sold with a premium, which goes to the miner—approximately $4,000 per kilogram, or about 6.2%. In addition, the gold typically has had to be segregated from other gold in order to be sold as Fairmined. That costs money, which can vary depending on the brand. At a time when the price of gold is over $1,900 an ounce, these extra expenses can be a burden.

ARM is piloting a system of certified credits, meant to lower the cost associated with tracking the gold through the supply chain. The system lets buyers pay miners the standard premium for the gold, but instead of importing the actual Fairmined metal, they receive credits that let them call the gold Fairmined. They then buy gold from standard (non-Fairmined) suppliers. Meanwhile, the Fairmined co-op sells the metal locally.

This allows brands to save money by not shelling out extra cash to segregate Fairmined gold from other types. The miners also save on export fees and still get the premiums. The problem, some might argue, is that the brands aren’t using actual Fairmined gold.

But ARM chairman Patrick Schein argues that that shouldn’t matter, as the miners are benefiting regardless. “The segregation is a pain for the brands,” he says. “This lowers their segregation costs, which don’t go to the miners or for development; they go to Brinks or the banks. It’s the same impact, just not the same gold.”

Schein notes that for items like the Nobel medal, Fairmined gold is used.

Fairmined’s second problem stems from the first. Many jewelers see “recycled gold” as a way to assuage the concerns of conscious consumers and have favored it over the pricier Fairmined alternative. Recycled gold has several advantages over Fairmined: It has no premium, and many consumers consider it just as ethical as Fairmined—perhaps more so, given the ubiquity of the word recycled and the concept of what it means.

And yet consumers may not know that “recycled gold” actually has multiple definitions, and in some cases the gold was mined very recently. This has led industry groups to ask the Federal Trade Commission to forbid the term.

“Recycled gold is just gold that changes form,” Schein says. “It has been happening for 4,000 years. It has no benefit for the environment. You cannot be responsible or ethical if you leave the ASM miners behind.”

Swiss Better Gold

Swiss Better Gold, an association based in Tannay, Switzerland, runs an initiative with a similar model as Fairmined. It sources from ASM miners but uses a business-to-business, rather than business-to-consumer, model. The gold also carries a smaller premium.

“It’s not as expensive as other brands, but the premium is sufficient to make a difference on the ground,” says Diana Culillas, Swiss Better Gold’s secretary general.

The program was started with support from the Swiss government, but the eventual goal is for it to become self-sustaining.

As a business-to-business brand, Swiss Better Gold may not have the same consumer appeal as Fairmined, though brands like it for its social impact and traceability, Culillas says. Among the big brands that belong to Swiss Better Gold: Audemars Piguet, Breitling, and Chopard. The association just opened membership to companies outside Switzerland, which means U.S. brands and retailers can join.

“Recycled gold offers no traceability,” Culillas says. “This lets the brand have a traceable supply chain. They know where the gold comes from and what kind of impact it has.”

Moyo Gems

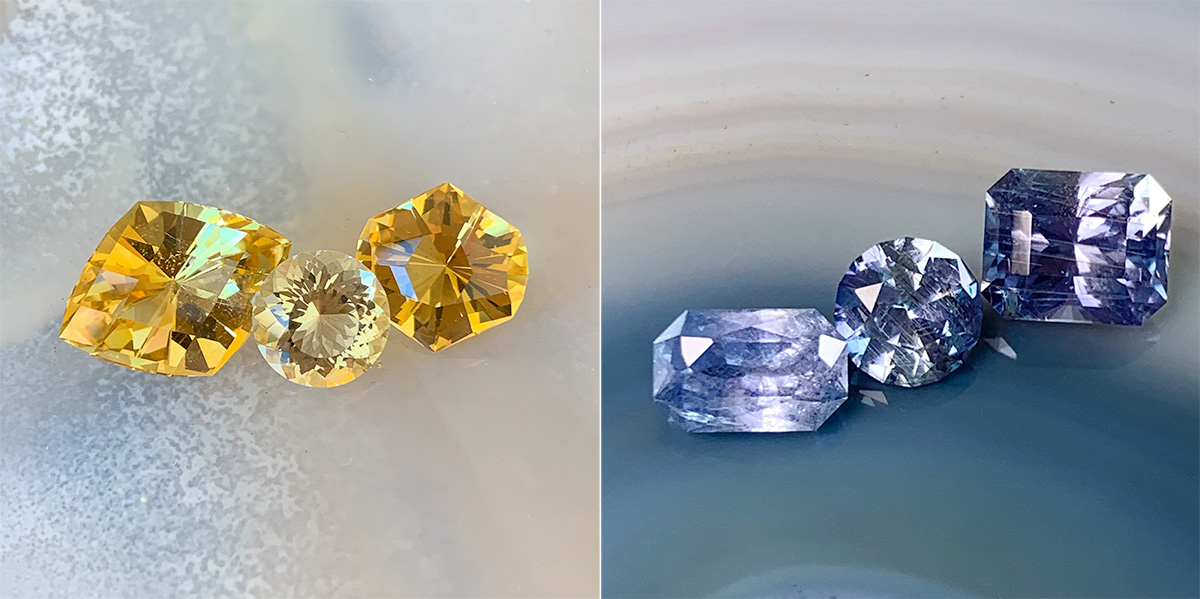

Moyo Gems—its name means heart in Swahili—sells tourmaline and garnets mined at mostly female co-ops in Kenya and Tanzania. Unlike Fairmined, the program doesn’t charge a premium for its gemstones, but the workers benefit from the shorter supply chain: Instead of the gems passing through a number of hands and getting marked up with each transaction, they are sold direct-to-market, which means the co-op can retain 90% of their value.

The backing of an NGO has proved to be a huge advantage, Pact’s Villegas says. “Other initiatives don’t have that kind of apparatus behind it,” she says. “There are advantages of having both a charity and a business structure. The philanthropic backing lets you scale, and the commercial part is fully self-sustaining.”

The project started with 81 workers; its workforce has since ballooned to 900. Despite the preferable conditions under which most Moyo Gems are unearthed, however, artisanal mining will never be perfect or pretty.

“We have had some pushback when consumers see pictures of the mines,” Villegas says. “They’re expecting the super-hygienic mines that you see in the sustainability reports of De Beers and Lucara, with millions of dollars behind them. The reality of what ASM looks like is still surprising to people.”

The program “doesn’t focus on poverty,” Villegas says. “We focus on the people and the joy.”

So far, that’s worked. The gems can be bought at Brilliant Earth and other ethically minded jewelers.

“There are a lot of beautiful products out there,” Villegas says. “What sets Moyo apart is the beautiful story.”

Root Diamonds

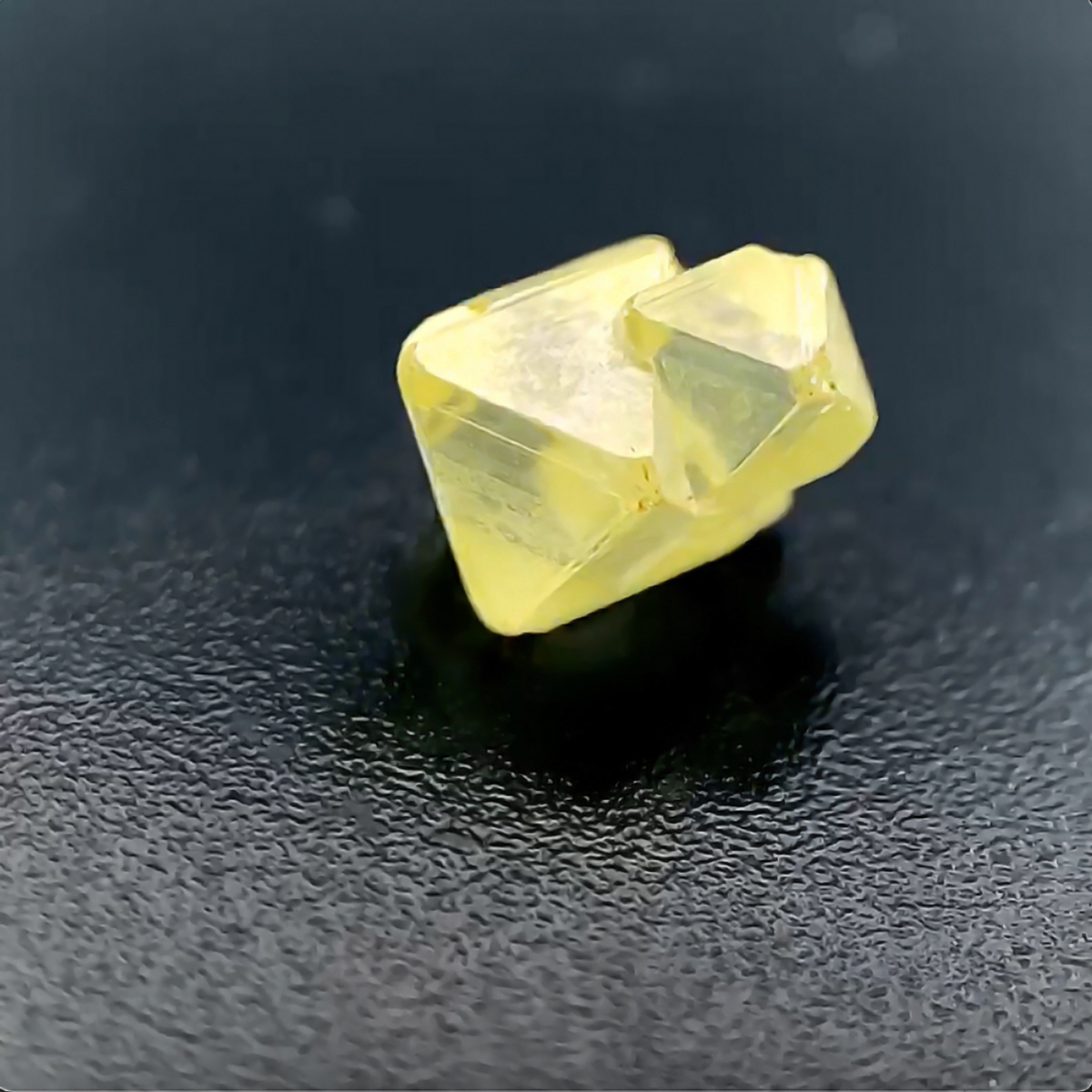

Root Diamonds is still getting off the ground, but it’s hard not to get caught up in the enthusiasm and passion of its organizers. The initiative—under which diamonds would be cut and jewelry designed in Sierra Leone—was started by Fas Lebbie, a Sierra Leone native and U.S. graduate student who grew frustrated when researching the problems in his country’s diamond industry and decided to do something about it.

He reached out to Maarten de Witte, the legendary gem cutter who has worked at Hearts on Fire and Eight Star. The program morphed into something else after de Witte was contacted by Synova, the Swiss manufacturer of a cutting machine called the DaVinci Diamond Factory. “They said, ‘How can our machine help artisanal miners?’” recalls de Witte, now a consultant to Root. “My gut reaction is that this machine is automated, it’s going to put people out of work.

“Then I thought we could put in a couple of workbenches [for cutting], but that doesn’t take Africa into the future,” de Witte says. “With [Root] we can still hire polishers, and we can hire and train technicians. That can add value, it can create opportunities, it can help train the next generation.”

The concept also might prove cost-efficient, de Witte says, and provide a template for cutting in artisanal areas. “You put in a 200-person factory, you are going to need a deep-level mine, which you can’t really have in artisanal areas.”

While the machine will be in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, Root would also like to set up a jewelry design school in Kono district, the source of most of the country’s diamonds. Root has only a few diamonds available now but hopes to have more for the industry at large in the next year or so.

De Witte says Root and projects like it provide “feel-good” stories for an industry that needs them. “You want a ‘diamonds do good’ story?” he asks. “Botswana is a no-brainer. It has some of the best mines in the world.

“But let’s take a worse-off country: Sierra Leone,” de Witte says. “It’s synonymous with blood diamonds, and it hasn’t budged an inch in the last 20 years. Wouldn’t it be great if we had a good story to tell there?”

Top: Moyo Gems miner Mwanamvua at the inaugural market day (photo courtesy of Anza Gems)