I’ve looked at tons of company pages about the eco-impact of lab-grown diamonds, and I’ve noticed one thing: Very few talk about the eco-impact of lab-grown diamonds.

Instead, most of them talk about the eco-impact of mined diamonds and why lab-grown diamonds compare favorably.

Man-made diamond companies regularly call their product “eco-friendly” and “sustainable.” It’s now become a basic part of the lab-grown pitch, a way of letting consumers know they are not just getting a cheaper product but a meaningful one (though price remains the driver, most say). Reporters often print these claims, uncritically. And with concern about climate change clearly on the rise, that could prove a potent positioning.

Yet, these claims are rarely examined—and terminology is often extremely fuzzy. Charlotte Vallaeys of Consumer Reports notes that a term like “environmentally friendly” has no real definition and “could mean whatever the company wants it to mean.”

The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) Green Guides explicitly discourages “broad, unqualified general environmental benefit claims like ‘green’ or ‘eco-friendly,’ ” as they are “difficult to substantiate, if not impossible.” Perhaps for this reason, the more circumspect lab-grown companies tend to use word sustainable.

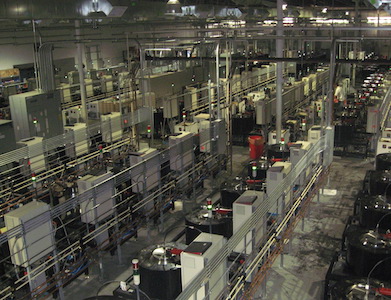

Yet, man-made diamonds are unusual for a “sustainable” product. They are produced in factories. Granted, they’re mostly clean, modern, non–assembly line factories. But they’re not greenhouses, though some use that term. The machines that produce diamonds “require constant energy, 24/7, running huge microwave-heat generators,” says one ex-employee.

So the question remains: Do lab-growns effect the environment less than mined stones?

Generally, these claims have two bases: less energy usage and less environmental damage caused by mining.

Let’s look at the energy question. Lab diamonds are produced in two ways: high pressure, high temperature (HPHT) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD).

One veteran grower gave JCK these numbers:

A single-stone HPHT press will use 175–225 kilowatt hours (kWh) per rough ct., which would end up around 650–1100 kWh per successful polished ct. A modern larger multistone cubic HPHT press will use 75–150 kWh per rough ct., which would end up around 350–700 kWh per successful polished ct. Cubic presses come in many sizes, and I would not be surprised if a converted industrial press uses twice that power with a lower success rate and polishing yield.

[A CVD producer] told me [it used] around 60–120 kWh per rough ct. and 1,000–1,700 kWh per polished ct. There is more unused rough from CVD since they are cube shape, which is why those ratios are higher.

Jason Payne, founder of ADA Diamonds, has said the “most efficient” growers use 250 kWh per ct., which is the same amount of electricity the average U.S. household uses in 8.7 days or the electricity to fully charge a Tesla two-and-one-half times. But most use about 750 kWh to grow a diamond, he says.

Singapore-based IIa Technologies claims it uses 77 kWh per ct. to grow diamonds, more than three times its predecessor, Gemesis, which once said it used only 20 kWh. But it’s unclear if these numbers account for mistakes or the post-growth treatment typically done to CVD diamonds.

Diamond mining operations show a similar range of data, which isn’t surprising since there are many kinds of mining. Gem excavation in its simplest form means “grabbing a shovel” and digging, as Diamond Foundry puts it. That requires little energy. The artisanal sector sometimes harms the environment in other ways, which shows why these numbers shouldn’t be looked at in isolation.

In a 2013 working paper, Saleem Ali, an environment professor at the University of Delaware, found that Australia’s Argyle mine uses 7 kWh to produce 1 ct., De Beers’ operations use 80.3 kWh per ct., and Diavik uses 66 kWh per ct. Alrosa didn’t specify its energy use but tells JCK it’s been “significantly decreased.”

A 2011 ABN Amro report, using numbers from growers Gemesis and Apollo (both no longer around) found that it takes an average 26 kWh to grow a round diamond and 57 kWh to mine one.

Yet per-carat averages might not be the best measurement. Not all carats are alike. Argyle produces mostly low-quality rough. And a better-quality diamond takes a lot more time, and energy, to grow.

In an interview with JCK, Ali warned that mining company numbers sometimes don’t give the full picture, as they may not account for the costs of exploration and transportation to the sometimes-isolated mine sites. But he says that lab-grown companies also need to provide more info, as some use mined metals in their process.

He also stresses that the source of the energy is as important as how much is used. This also varies.

Industry analyst Paul Zimnisky says that most HPHT diamonds are produced in China, which sources 55 percent of its power from coal and 20 percent from hydro. In India, another major producer, 75 percent of grid power comes from coal and 10 percent from hydro. Singapore, home of IIA, uses little renewable energy.

Diamond Foundry says it’s been “certified carbon-neutral,” though it purchases solar credits to get there. Certifier Natural Capital Partners declined to talk to JCK about its methodology but pointed us here. “The steps required for certifying carbon footprint are a full third-party audit,” says Diamond Foundry CEO Martin Roscheisen via email. “It is comprehensive—it includes employees driving to work, all of our operations worldwide including polishing, etc.”

On the mined side, Diamond Producers Association (DPA) CEO Jean-Marc Lieberherr says that mining companies are looking at reducing their carbon footprint, and De Beers hopes to soon make some mines “truly carbon neutral,” using carbon from the diamonds. The DPA recently hired Trucost, a division of S&P Global, to assess its members, which comprise 75 percent of world production.

Trucost found that the carbon footprint is the biggest environmental issue in diamond mining—and like Payne, it’s come up with a consumer-friendly analogy: “Carbon emissions associated with one polished carat are six times less than those of one passenger on a one-way flight from Los Angeles to New York.”

Which side wins the energy wars? It’s not cut and dried, says Ali. “Depending on the process and the location of the mine, the data can be highly divergent and cannot be used as a singular measure of environmental impact,” he wrote. “[T]he energy usage for synthetic diamonds on a per-carat basis may still be considerably greater than for mined diamonds because of issues of scale.”

So, in some cases the lab-grown companies compare favorably; in others, they don’t. We need more info, and more transparency around these numbers and claims, to get the full picture. These are both energy-intensive processes. For now, the eco-energy claims are, as the FTC puts it, “difficult to substantiate.”

The second eco-argument says that diamond mining “rips up” the land and damages fragile ecosystems, including wildlife and lakes. One frequently quoted statistic is it takes 250 tons of earth to find 1 ct. of polished diamond.

Advocates say that digging diamonds is considered less damaging than other kinds of mining, like coal, iron, and gold.

“The footprint of a diamond is narrow,” says Lieberherr. “There is no chemical used in extracting diamonds from the ore, and water gets largely treated and recycled. Modern mining is done under very stringent environmental controls from local governments and communities. Canada, for example, has some of the most stringent environmental norms in the world.”

Miners say they try to mitigate their impact. Alrosa reduced its water usage by 57 percent in 2017, it says, and by 60 percent over the last five years.

Trucost calculated that DPA members’ collective negative impact on land usage, water depletion, pollution, and waste is compensated by the positive benefits associated with their biodiversity programs. All told, they’ve conserved 260,000 hectares of land, Lieberherr says.

Still, issues do pop up, particularly in poorly managed areas. Perhaps the worst recent issue came from the Marange diamond fields in Zimbabwe, where miners were accused of dumping chemicals in the water. Incidents like these are relatively rare, though hardly nonexistent, and the (non-DPA) companies that allegedly did these things bear responsibility for them. But it shows that mining can have a wide range of effects and why it’s better to know what you’re getting.

Ali feels that when you factor in things like water usage, “there is no question that synthetic diamonds will be less impactful [environmentally] than mined diamonds.”

Yet, he’s reluctant to endorse lab-created diamonds because, again, there’s a bigger picture. Some 10 million people work in the diamond industry, in some of the poorest areas of the world. The diamond industry contributes $8 billion a year to Africa.

That was echoed by just about every nongovernmental organization (NGO) that JCK talked to. It’s striking that no conservation group has endorsed lab-grown diamonds—though plenty have endorsed electric cars. We reached out to environmental organizations on this issue. None responded.

Joanne Lepert, executive director of Impact, a Canadian NGO active in African development that’s often critical of the diamond business, says that “for us, sustainability is linked to economic development, it’s about structural change, it’s about women’s rights, and it’s about inclusive participation. Synthetic diamonds don’t do any of that. They will take that away. It’s closing the door on the micro-producers to enter the international market.”

Brad Brooks-Rubin, policy director of the Enough Project, another sometimes-critical NGO, has said, “[Lab-diamonds] focus on the environment, but a bigger question is, is it ethical to guide people away from buying diamonds in developing countries, where a million people or more rely on the work?”

Estelle Levin-Nally, founder of Levin Sources, which works on better governance in the natural-resource sector, says, “It depends on what your consumers care about: Do they care about the environment or poverty and people who want to eat and feed their family?”

Given the way she framed that question, there’s little doubt where she comes down.

“If you believe in technology and getting rich, then go with lab-grown diamonds,” she says. “If you believe in the fair distribution in income across the whole community, you might want to rethink that.”

This isn’t about the diamond industry being good or bad—the business has plenty of both. It’s about an undeniable fact: Millions of people and their families depend on diamond mining, and if you hurt their business you risk hurting them. The economies of poor countries are also fragile ecosystems.

Some argue these millions of workers should transition to more eco-friendly livelihoods. But they do it because there’s no other choice. There’s no solar-panel business waiting to be born in Sierra Leone. Ali has pointed out that before Botswana became a major diamond producer, its main business was cattle ranching. That was less lucrative and also bad for the environment.

On the plus side, lab-grown diamonds have probably kept some Indian cutters employed and maybe even some small jewelers in business. Industrial synthetics have shown enormous promise for everything from computers to health care. And mining reserves are dwindling, though it will take decades before they actually run out.

There are no easy answers here. But perhaps we’re looking at the wrong question. Maybe we shouldn’t be looking at the ecological and social impacts of these broad categories, but the impact of each specific stone. People shouldn’t buy a “sustainable” item without knowing its precise impact.

That would require a more transparent supply chain. For now, both sectors lag on this: Mined diamonds and lab diamonds are usually aggregated and on occasion mixed together. And they both share the same risks: A 2013 report from the Financial Action Task Force warned that created diamonds are just as vulnerable to money laundering as their mined counterparts.

According to Common Objectives, a sustainable fashion initiative, a transparent business maps its supply chains, details the provenance of its supply, and reports its social, environmental, and financial results. This transparency should be standard for any business that boasts that it’s “sustainable” or “ethical,” and, needless to say, “transparent.”

For now, saying a diamond is lab-grown is like saying it has a Kimberley Process certificate. It tells you some info, but not all. Even if lab-growns are more eco-friendly than mined, that’s an arguably inappropriate label to put on an item produced with large amounts of nonrenewable energy. If a cookie contains 30 percent less sugar, that doesn’t make it a health food.

Levin-Nally is hopeful that the lab-grown boom will boost transparency in the diamond sector, as jewelers realize that many customers really do care about these things.

“I’m not against lab-grown diamonds,” she says. She notes there is a growing movement toward climate-smart mining, including a new initiative by the World Bank. “If lab-grown diamonds help with that, bravo.”

I’ll be covering this subject in a future feature in JCK, so I welcome more info, feedback, and data. We also discussed this issue on the pilot episode of JCK’s new podcast, “The Jewelry District.” Finally, for a further look at this topic, I recommend this article in Jewellery Business.

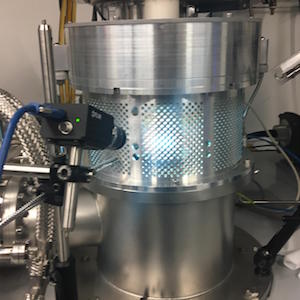

Top: A diamond being produced at the Gemological Institute of America (image courtesy of Rob Bates)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine