Last week, I spent a few days at the JCK office at One World Trade Center in lower Manhattan sorting through issues of the magazine dating all the way back to 1869 (!). (We’re preparing for our 150th anniversary in 2019, and it all begins with a deep dive into the archives.)

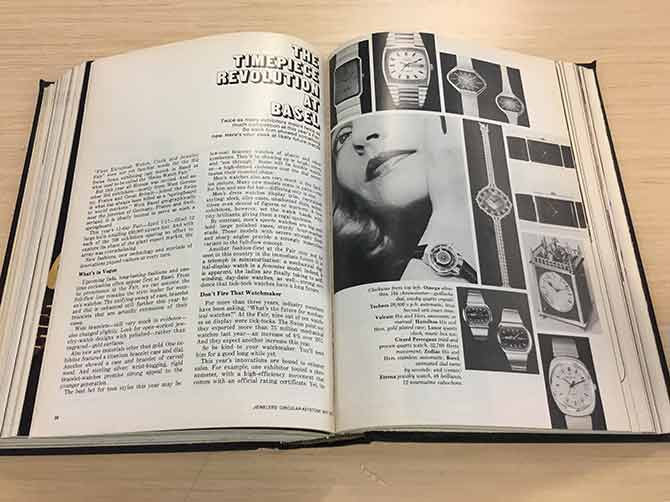

The 1973 volume (the year I was born) called my name. In its May issue, I found an article called “The Timepiece Revolution at Basel” and couldn’t help but smile. So much has changed for the show in the 45 years since the piece ran—and yet, more has remained the same.

Long known simply as the Swiss Watch Fair, the then-56-year-old Swiss show rolled out a new name in 1973—the First European Watch, Clock and Jewelry Fair—and with it, a new focus on exhibitors from across Europe. The JCK article documented the season’s trends, which will sound remarkably familiar to today’s watch buyers: “materials other than gold,” “sleek, slim cases, unadorned dials,” and “new self-winding chronograph calibres.”

The difference, of course, was the article’s exuberant take on the fair’s future—a sharp contrast to today in light of last week’s news that the Swatch Group will not exhibit at the 2019 Baselworld fair; the subsequent resignation of René Kamm, the CEO of Baselworld’s management company; and the attendant Sturm und Drang over how—or if—the fair will recover.

In 1973, Basel lasted an incredible 11 days. From April 7 to 17, 708 exhibitors—twice as many as the prior year—“filled 12 large halls totaling 430,000 square feet,” according to the article.

Today, the show is shifting in the other direction. As news director Rob Bates noted in his story about the Swatch Group’s decision: “This year, the fair housed a little more than 600 exhibitors, about half the companies that exhibited in 2017. Management also trimmed the fair’s length from eight days to six.”

There’s no denying Baselworld’s downward trajectory, as exhibitors and buyers question its relevance in an increasingly consumer-driven marketplace. But let’s not forget that, unlike 1973, when the Swiss were still reeling from the introduction of Japanese-made quartz watches (charmingly called “tick-tocks”), the health of the watch business in 2018—particularly the mechanical watch business—is not up for debate. (“Strong rise in June for a very good first half,” the Swiss Watch Federation boasted in its most recent exports update.)

If I’ve learned anything about this industry since I began writing about watches in 2000, it’s that, above all else, it is cyclical. Everything comes back around. Even fairs. There is talk of Baselworld repositioning itself as a communications platform or a showcase for independent watchmakers. Or perhaps a consumer-driven event, along the lines of how its rival, the SIHH show in Geneva, is evolving.

Regardless of how Baselworld copes with its new reality, here’s a bold prediction: In 50 years, we’ll still be talking about it.

P.S. Also of note in the May 1973 issue of JCK was a letter by editor Donald McNeil entitled “Can Lab-Made Stones Elude Detection?” In it, he refers to “a question that has nagged many a thoughtful jeweler like a nightmare: Will it continue to be possible to distinguish synthetic gems from the natural?” Nearly five decades on, we’re still obsessing over the same nightmarish scenario. The more things change, apparently, the more this industry doesn’t.

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine