If this thing makes you crazy (or this or…ugh, nevermind), don’t get mad—get MAD. As in, NYC’s Museum of Arts & Design, which debuted a new jewelry exhibit last month that can only be described as chillingly, hauntingly relevant to conversations related to the complexity of U.S.–Mexico border relations.

Titled “La Frontera: Encounters Along the Border,” the exhibit gathers 62 specially commissioned works from 48 international artists in a tiny, quiet corner of the museum, filling the space with colorful, stirring explorations of the border environment within geographic, ecological, political, economic, social, cultural, and ideological contexts.

“La Frontera testifies to the power of intimate personal objects within the epic human and natural dramas that unfold daily along the U.S.–Mexico border,” says Barbara Gifford, co-curator of the exhibition, along with Lorena Lazard and Mike Holmes. “Whether made in 2013 or in 2017, these are poignant jewelry pieces that recount human stories of peril and hope and have a great deal of anguish in them.”

For example, Cristina Celis’ Dactilar pendants reflect what people are willing to do to their own bodies for the sake of staying in the U.S. Many migrants are fingerprinted and photographed, and these records can cause them to be deported. As such, the practice of erasing the information enclosed in the fingers is common. (Just to clarify, “erasing” can involve burning fingertips on a stove, dousing fingers in acid, and self-mutilation using razors.)

So, no, this is not a jewelry exhibit designed to titillate with Edwardian diamond tiaras or supreme examples of the art deco style. You probably won’t find inspiration for your next collection either.

But here’s why you should go.

“The jewelry in La Frontera showcases the narrative possibilities of jewelry,” says Gifford. “To see jewelry objects, often dismissed as decorative, take on the politics of the U.S.-Mexico border is inspiring and broadens the possibilities of what jewelry can be.”

Young and emerging jewelry artists are likely to find the show especially compelling. “It may give them the confidence to explore what is inside of them and express it through their chosen art medium, no matter the subject matter,” adds Gifford.

The exhibit also serves as a great reminder that the American jewelry industry is defined by a rich, diverse tapestry of immigrants and their descendants.

La Frontera will be on view at MAD through September 23.

See highlights from the exhibit and their inspirations as described by MAD, below.

Kevin Hughes’ untitled necklace, made from detritus of jug handles, references the plastic jugs of water left by aid workers along the border, creating life-saving oases in an otherwise treacherous and defeating desert environment. (Photo courtesy of Mike Holmes/Velvet da Vinci)

Kevin Hughes’ untitled necklace, made from detritus of jug handles, references the plastic jugs of water left by aid workers along the border, creating life-saving oases in an otherwise treacherous and defeating desert environment. (Photo courtesy of Mike Holmes/Velvet da Vinci)

“No-Man’s Land,” a brooch by Judy McCaig, incorporates steel, silver, tombac, Perspex, paint, Herkimer diamond, and taramita to reference the mountainous, arid terrains, and natural dangers involved in crossing the border.

“No-Man’s Land,” a brooch by Judy McCaig, incorporates steel, silver, tombac, Perspex, paint, Herkimer diamond, and taramita to reference the mountainous, arid terrains, and natural dangers involved in crossing the border.

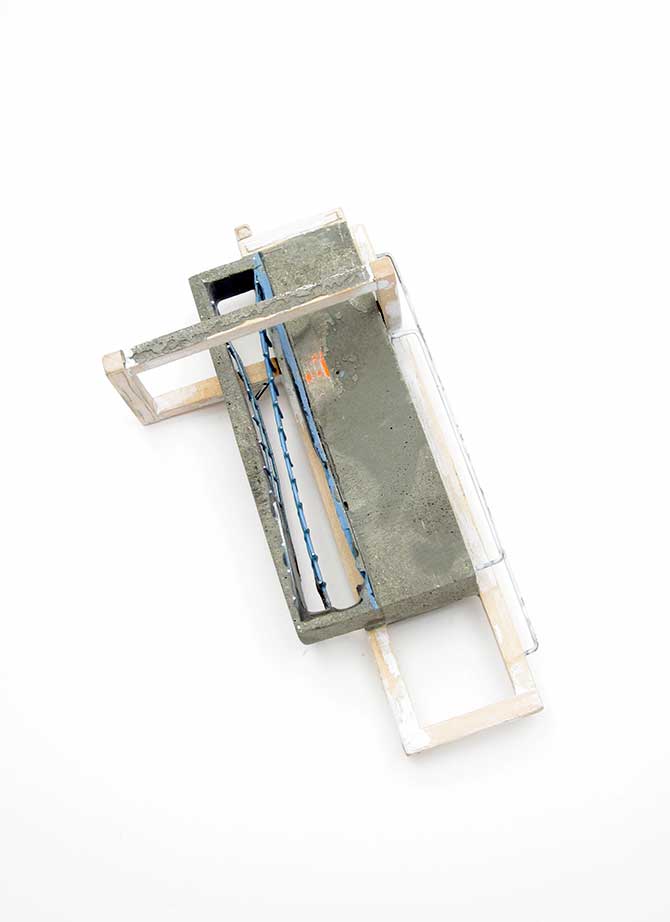

The “Reconstructed: Framed” brooch by Demitra Thomloudis attempts to make sense of the deliberate separation between countries through the lens of jewelry, finding a poetic accord between form, color, and texture, as embodied in a singular object of adornment. (Photo: Seth Papac, courtesy of Velvet da Vinci)

The “Reconstructed: Framed” brooch by Demitra Thomloudis attempts to make sense of the deliberate separation between countries through the lens of jewelry, finding a poetic accord between form, color, and texture, as embodied in a singular object of adornment. (Photo: Seth Papac, courtesy of Velvet da Vinci)

Martha Vargas’ silver necklace “Sueño y Realidad” makes a poetic connection between immigrants and the monarch butterfly migration that begins in March. Though each group travels to more hospitable destinations and faces natural dangers, butterflies are free to make these journeys unhindered by walls or politics. (Photo: tempusdesign.com.mx, courtesy of Velvet da Vinci)

Martha Vargas’ silver necklace “Sueño y Realidad” makes a poetic connection between immigrants and the monarch butterfly migration that begins in March. Though each group travels to more hospitable destinations and faces natural dangers, butterflies are free to make these journeys unhindered by walls or politics. (Photo: tempusdesign.com.mx, courtesy of Velvet da Vinci)

Top image: Julia Turner’s “Three Days Walking (Mourning Brooch)” is based on warning maps that show the dangers of crossing the border through the desert on foot. The maps depict routes clustered with red dots, each of which represents the location of a death, overlaid with circles indicating the distance on foot from the border. The brooch makes reference to Victorian mourning jewelry, which often contains a remnant of hair from the loved one lost. (Photo: the artist, courtesy of Velvet da Vinci)

Follow me on Instagram – @aelliott718

Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazineFollow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine

Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

Subscribe to the JCK Special Report