More and more labs are using artificial intelligence and automated grading to evaluate diamonds. Some think that will change the industry.

When the De Beers Institute of Diamonds, the diamond giant’s grading lab, first started using machines to judge color, researchers were surprised by the machines’ results and how they stacked up against their human counterparts.

“We immediately spotted there was something different about the color machine,” says David Fisher, principal scientist for De Beers Group Ignite, the miner’s innovation arm. “It was outperforming the human graders in terms of consistency.”

The machine, however, was far from perfect.

“It was really good as long as it was consistently churning out a standard color grade,” Fisher says. “But if you had something that was slightly off color, or something it hadn’t come across before, or the color was influenced by the cut of the stone, the machine couldn’t grade that.

“Humans are good at adapting,” he adds. “The machine needed to be taught.”

The Revolution Will Be Automated

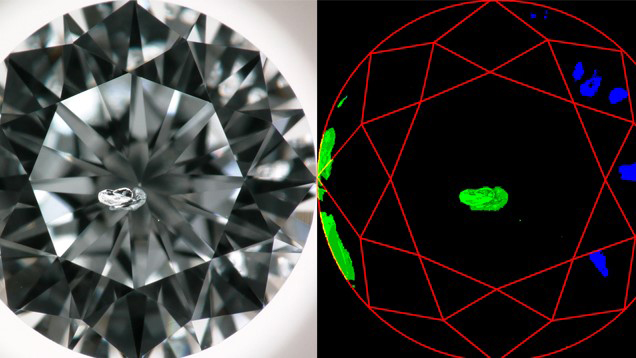

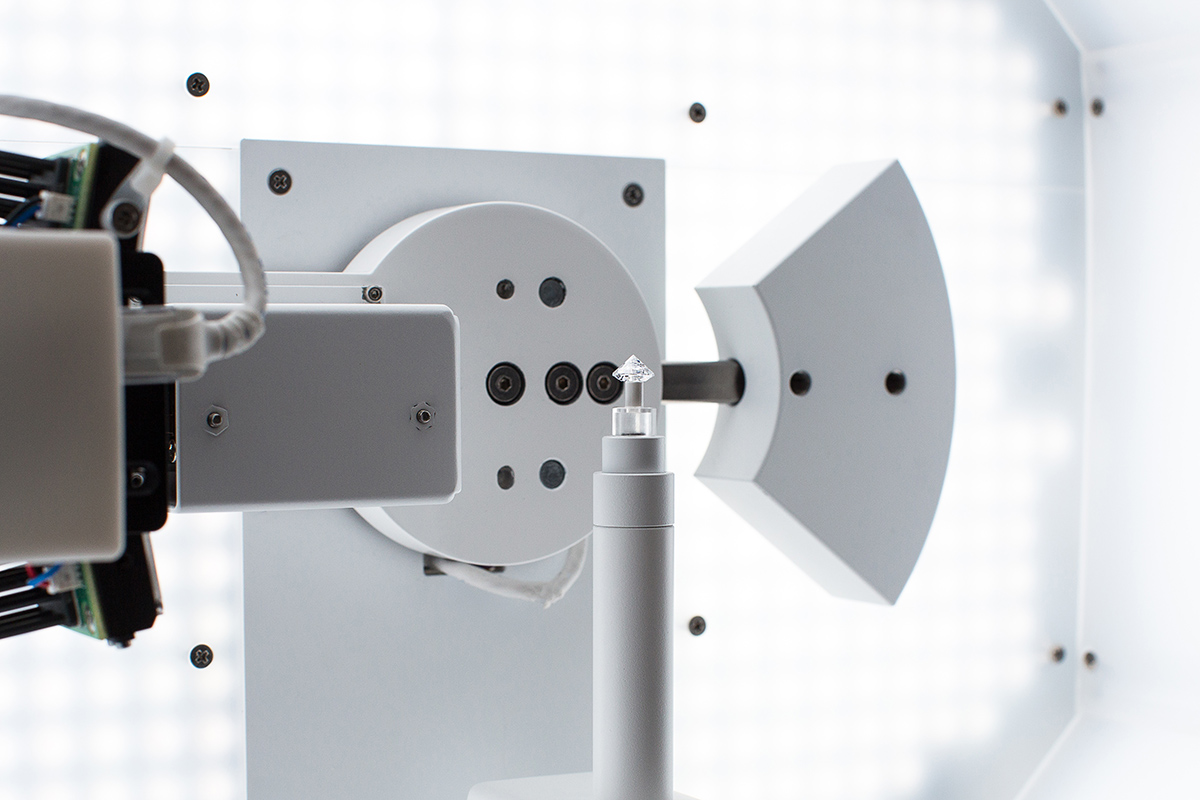

Diamond and gemstone grading is clearly becoming more automated. In recent years, machines that use artificial intelligence (AI) have come into wider use to measure color. Now, as AI improves, labs are using the technology to grade trickier measures such as clarity.

Yet, while experts agree that automated grading will be common in the future, there’s some debate on whether it’s ready for the present. GIA, for example, still uses human graders to back up all its clarity grades.

“Right now, we’re checking every stone because the technology is still evolving,” says Pritesh Patel, GIA’s senior vice president and chief operating officer. “There’s still room for improvement in technology before we can get to the level where we can let machines do everything on their own.

“In the future, we’ll see efficiencies,” Patel adds. “But right now, we are keeping our original processes.”

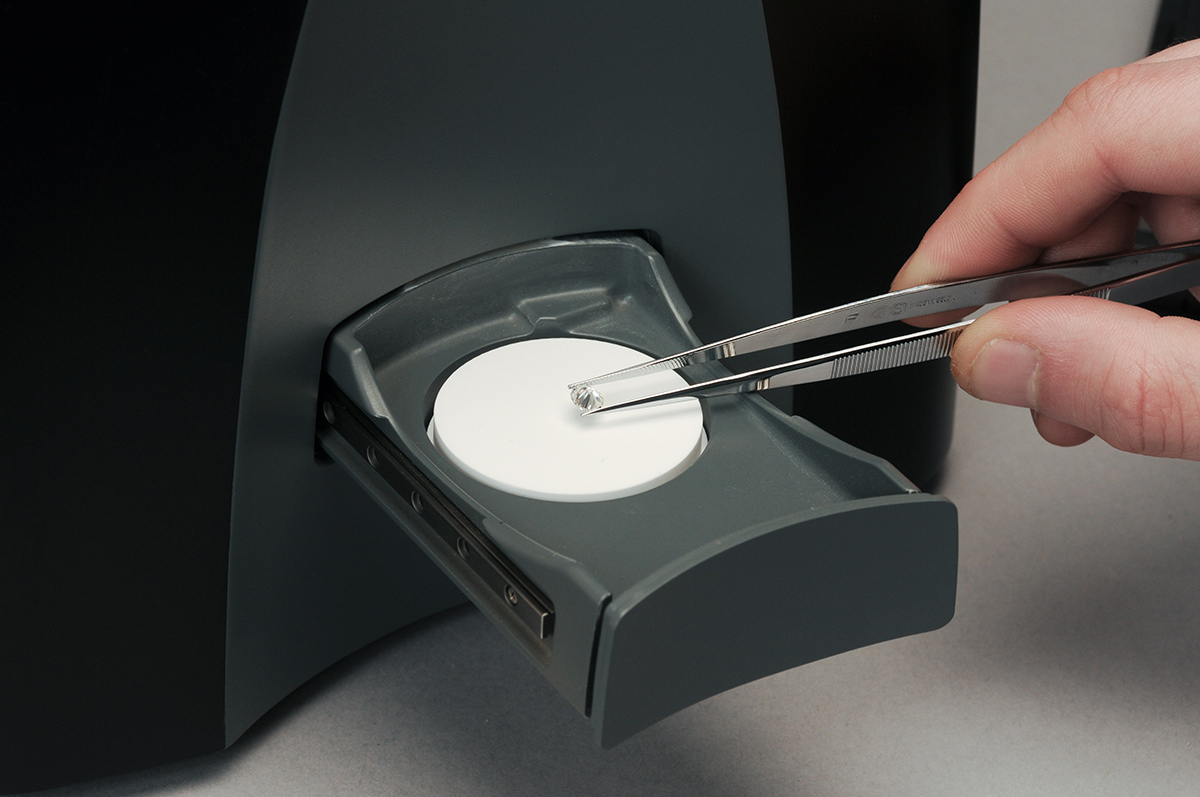

On the other hand, Sarine, the Israeli technology company, believes that its e-grading devices—including the recently developed Clarity-II—are good to go. “We don’t come to market with something unless we are certain it works,” says Matthew Tratner, general manager and vice president of Sarine North America.

Even so, Sarine is not rolling out all the devices to the wider market just yet. “Right now you can’t call us and buy the machines to set up a grading lab,” Tratner says. “The plan is to get [the clarity machines] into primary manufacturers in India, and then start working with retailers. By the end of the year, we hope to be in 25 manufacturers. That’s a lot of diamonds being graded on the network. It’s going to grow quickly.”

If the trade adopts the technology, it will change the business, Tratner predicts. “Diamonds will never have to leave the cutting factory” to be graded, he says. “That will add tremendous efficiency to the pipeline.”

Rage Against the Machine

In spite of his embrace of AI, Tratner admits the prospect of widespread machine grading has made some uneasy. “Some people don’t like change,” he says. “You have to get your head around the fact that there’s a new way to do things.”

Just about everyone acknowledges there are undeniable advantages in having machines grade diamonds. They don’t take breaks, vacations, or lunch. They can work all night. Their eyes don’t get tired. And they are generally consistent.

“Humans inherently have flaws,” Tratner says. “They can have a bad day, and that changes how they grade. A computer doesn’t have that.”

Diamond grading machines not only tend to be more consistent than human graders but also are better at spotting inconsistencies, Tratner maintains. “Diagnosing problems will be much faster.” And while machines may not be as adaptable as humans are, machine learning is improving. “The more that a machine grades, the smarter it gets,” Tratner says. “If you have one [human] grader that sees something, they don’t know that a grader 3,000 miles away has seen something similar.”

Not everyone, however, is convinced. Some in the industry note that AI-based grading is vulnerable to the same abuses as regular grading.

Angelo Palmieri, principal and chief operating officer of Gem Certification & Assurance Lab, based in New York City, says that so far he hasn’t seen any device that delivers the consistency he seeks. “We are all for anything that improves the accuracy and consistency of diamond grading,” he says. “AI grading has a lot of benefits, and a lot of potential risks.

“A lot depends on who sets the machine,” Palmieri adds. “It could present a veil of authority that might be misplaced. It’s like blockchain was the buzzword five years ago, because it was immutable. But if you put garbage on the blockchain, then you have immutable garbage.”

In Sarine’s case, Tratner says the company will set the standards, and all the grading will be performed on its cloud-based servers. “The person running the machine can wish for all the VSs they want,” he says. “The operator has no influence on the grade.”

For Mark Gershburg, founder and CEO of Gemological Science International, another New York City-based lab, however, the idea of using machines provided by a third party that handles grading doesn’t make sense. “How can you issue a report if someone else has done the work for you?” Gershburg asks. “You don’t know how these instruments work. There are a lot of unknowns for us.”

Gershburg notes that while his lab is looking into automated grading, it specializes in grading mounted stones, which is likely to prove challenging for machines.

Are Thousands of Jobs at Stake?

Others worry that if diamonds become entirely graded by machines, that could wipe out thousands of diamond grading jobs. It could even, theoretically, mean the end of grading labs.

Tratner doesn’t see it that way. “If you talk to gemologists, they are some of the happiest people with us,” he says. “How many gemologists want to grade diamonds all day long?” He notes that, with harder-to-detect treatments and synthetics on the market, “there will be plenty for gemologists and laboratories to do. We’re taking out of their hands the thing they don’t want to do.”

Not surprisingly, the labs don’t see themselves going away any time soon. For one thing, there are certain categories of diamonds for which machines are harder to program.

Fisher says that De Beers determined it’s possible to do automated grading of fancy colored diamonds, but “they are so rare and valuable, we have always said, ‘What’s the business case for doing it?’” Rarity may also prevent machine grading of higher-clarity gems, he says.

“The big thing is having an unbiased data set,” Fisher says. “Gathering data across the board is difficult. When you are trying to establish that boundary between VVS and internally flawless diamonds, there’s not much data available.”

Fisher also says humans are best used for grading diamond polish, which requires making “subtle distinctions.”

Patel agrees that, while there will be fewer humans involved in diamond grading in the future, they will still play a role, albeit one more focused on complex and high-value gems. “Certain stones will always require human eyes.”

Top: Getty Images