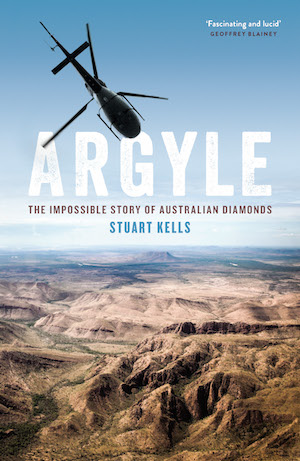

Last year, Australia’s Argyle diamond mine closed after 37 years of operation. This month, Melbourne University Publishing released Argyle: The Impossible Story of Australian Diamonds, a comprehensive history of the mine by Stuart Kells.

Here, Kells (pictured), a writer and adjunct professor at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, talks with JCK about the mine’s origins, why its impact is still felt today, and his favorite stories from its 37-year history.

JCK: A lot of diamond mines come about based on one person’s lone quest. Was that the case with Argyle?

Stuart Kells: That person was Ewen Tyler. There was an important geologist in the 1940s who had hypothesized that the geology of the Kimberley [region of Australia] was similar to the geology of the diamond-bearing parts of South Africa. Ewen Tyler was a student of his.

In the 1960s, Ewen was working for one of the big mining houses in London and they were looking to diversify geographically, and he pushed for them to set up an operation in Australia.

What’s the area like around Argyle?

It is very remote. Perth, the capital city of western Australia, is more than 2,200 kilometers [1,367 miles] from the mine site. It’s a very different part of the world. It’s a real kind of geologist playground, with all the different features and volcanic features and plateaus and amazing-dome like structures.

It’s a tropical area—in the summer, it rains torrential rain. So the creeks turn into rapids. But in the winter, in the dry season, it’s very hot and dry. It’s a place of extremes. It’s quite hard to build roads and do any sort of construction there. It’s also a very sparsely populated part of Australia and a very wild part of Australia.

It’s interesting that the area is called Kimberley, as Kimberley, South Africa, is considered a birthplace of the modern diamond industry.

That’s right. They are both named after the same person, too, because they were both obviously part of the British Empire. The Earl of Kimberley was one of the key colonial administrators. It’s just by coincidence they’re both named after the same person.

Argyle was known for its unusual mix: low-end “smalls” and high-end color.

The average diamonds there were brown. Most of the diamonds were relatively low-value diamonds destined for industrial uses. And at the time, the idea of brown diamonds was that they were a bit of a low-status diamond. There wasn’t a lot of respect for them in the diamond industry and among jewelers.

But an important part of the Argyle story is the rebranding and the reconceiving of the brown diamonds as champagne and cognac stones and marketing them that way. So, with that repositioning, they were able to move diamonds that would otherwise have been industrial diamonds, and to sell them into fashion jewelry retailers and mall jewelers. They really created a whole different price point for diamond jewelry.

Initially, Argyle sold its production through De Beers’ Central Selling Organisation. But you talk about how Argyle was controlled by Rio Tinto, which was a very different partner than what De Beers was used to.

That’s right. Most of its previous partners had either been governments or projects that were funded and owned internally as part of the De Beers and Oppenheimer business group. It was quite an unusual situation. Initially, the Australians were very new to this. There weren’t many people in the joint venture that had much time and experience in the diamond business, and they felt early on that the best way to market such a huge quantity of diamonds was to go through the De Beers system.

They felt like they had agreed to good terms with De Beers in the marketing contract, but in the day-to-day sorting and classifying, they were getting the short end of the stick. And so the Argyle partners did a bit of a test, where they had some auditors look at some parcels of diamonds to test whether the De Beers sorting was fair. They decided through that process that it wasn’t. That was one of the reasons why they decided to go it alone.

That was a big shock for De Beers, because even though Argyle produced a high proportion of low-value diamonds, it was so large that it did have market power.

Many think that was the beginning of the end of the “single-channel” system.

It definitely did force a change, because De Beers suddenly didn’t have the same degree of control over production and supply. Argyle proved that you could comfortably mine and sell diamonds outside the De Beers universe. It also meant that there were major mines and mining companies that were building their own expertise in diamond mining and in diamond marketing.

It was a real erosion of De Beers’ power, and that was one of the major catalysts for De Beers to reposition itself more as a luxury brand, and to focus more on the selling of diamonds and less about controlling overall production.

Do you think Argyle made the right decision?

[The company] spent a lot of time thinking about whether it was the right move. It turned out to be the right way to go, and one of the reasons why was it had that very deep relationship with the Indian cutting industry and polishing industry, and there was the scale in India to handle its production.

At one point, De Beers tried to gain control of Argyle.

There was a battle to control Ashton Mining, which had around 40% of the mine. For a little while, ownership of the whole mine was in play. De Beers was one of the key bidders for Ashton, but it was unsuccessful in the end. In a sense, that was one last-ditch attempt by De Beers to control Argyle and to control most of the market.

Argyle became known for its pinks. Were they a big part of the mine’s revenue?

They were a very profitable part of the mine, even if they were proportionally a very small part of its production. They also increased awareness of Argyle. The format of selling the pinks was a bit of a masterstroke, using those international viewings and exclusive tenders to create a certain amount of glamour and interest around the pinks. It became a real pillar of the annual diamond circuit and built an important luxury brand in the Argyle pinks.

In Australia, is there a lot of awareness of Argyle?

I think awareness of the pinks has grown in the last few years, but I think it’s fair to say that the mine is more famous outside Australia than it is in Australia. It was in some ways more famous in South Africa or in New York or in London.

What is Argyle’s legacy?

I think it has multiple legacies. In the market, there’s more acceptance of colored diamonds, including champagne and cognac. There’s the impact on De Beers and the overall diamond industry structure and diamond marketing arrangements. It proved that Australia has diamondiferous potential and can be a diamond player. There’s further exploration happening in Australia now, and some of the people involved in Argyle are involved in that.

There was a local legacy as well. In Australia we have had, like many countries with major mining industries, a long history of good and bad engagement with traditional owners and First Nation people. One of the legacies of Argyle was learning lessons about how to balance economic development with local Indigenous heritage and how to reflect the rights of Indigenous people in economic development.

How does that aspect look in retrospect?

The mine started [full production] in 1985, but the actual exploration and some of the early agreements go back into the 1970s. That was a time when legal frameworks for Indigenous rights in Australia were very poor, very weak. We have a concept here called Native Title, which essentially recognizes Indigenous ownership of traditional lands. That legislation and that legal principle didn’t exist at the time—it dates from the 1990s. So a lot of what happened at the mine and the trading off of local heritage for economic development happened before those legal frameworks were in place.

Part of the journey with Argyle over the last 35 years or so has been to be more fair and more sophisticated in recognizing Indigenous rights, and in engaging with tradition in a more appropriate and fulsome way. My sense is that the mine owners have learned from the experience over time.

So there are positive legacies in that area, but fundamentally the initial economic development of mines like Argyle was pretty one-sided, and there wasn’t a lot of legal protection of Indigenous rights. There was loss of sacred sites and Indigenous heritage. There’s a mixed legacy, but also a positive legacy around learning from that.

At the moment, the Indigenous owners are taking back the site, and they are involved in a positive way in remediating the site. There is an open question of future economic development in the area, because there was a high proportion of Indigenous employment at the mine, and that was obviously a positive for employment and economic development.

It’s left a gap in that area because it is such a remote part of the world and there isn’t a lot of industrial development there. So the future of that part of the world may lie in capturing some of its expertise and applying it to any future diamond mine in the area.

Were there any stories that really stuck out to you?

One thing that people were shocked by is that the processing plant was calibrated to break up the largest diamonds. That was about processing cost and the economics. People were really shocked to think of large diamonds going in one end of the processing plant and then getting crushed along the way.

The largest diamonds that were recovered at Argyle got through that process by chance. One had a strange elongated shape like a peanut, so that got through the crusher. It was around 42 carats. Then there was a 43-carat diamond that was stuck in a truck tire before it even got to the processing plant. So those two big diamonds got through just by chance.

Anything that really surprised you, writing about this?

The thing that really strikes me is that it’s a very big story—it was a big mine and it’s a really important product in a really important industry. But the things that drove it were small decisions and small conversations, individual people with ideas. There is a really interesting contrast of the big and the small and the personal relationships and the individual visions of what really drove it.

The Argyle story bridges those two eras of the kind of hero prospector who was walking around the bush independently to what we see today, which is industrial and scientific mining. The striking thing for me is there were so many times where the mine might not have gone ahead, including at the financing stages and at the political-approval stages. It’s amazing that it happened at all, and in large part it got through because of a whole series of small, almost random personal moments. So it’s a human story sitting behind a big economic and industrial story.

You can order Kells’ book on Amazon and, for those who want to support independent bookstores, Bookshop.org.

(Top photo courtesy of Melbourne University Publishing)

Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazineFollow JCK on Twitter: @jckmagazine

Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine