During World War II, more than 6,000 Jewish refugees fled Nazi-occupied Europe and headed to one of the few places that would take them: Cuba. Some of those refugees were diamantaires from Antwerp, Belgium, who established a thriving cutting and polishing industry on the Caribbean island.

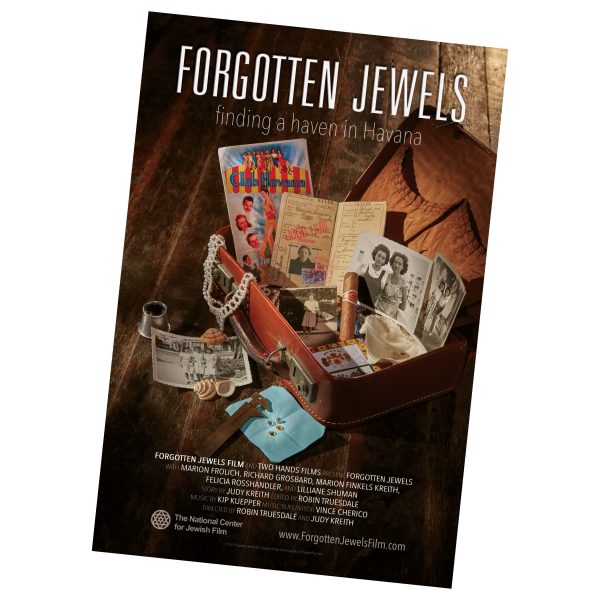

Judy Kreith’s family was among them, and, along with codirector Robin Truesdale, she has produced Forgotten Jewels: A Haven in Havana, a 45-minute documentary chronicling this largely unknown chapter in industry history.

On a personal note, my mother’s family was also one of those refugee families that settled in Cuba and worked in diamonds. So I was excited to hear about a film on this topic.

Here, Kreith and Truesdale discuss what they learned and the refugees’ lasting impact on the diamond business:

JCK: How did you decide to make a film on this topic?

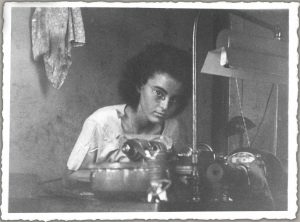

Judy Kreith: My mother Marion Finkels Krieth (pictured below) always told me stories of working in the diamond industry in Cuba. My main passion—and work—since I was a teenager has been dance. I took a workshop on Cuban dance and decided I wanted to study that style of dance in Cuba. I asked if my mom could go with me. So we went to Cuba in 2000. It turned out to be a life-changing experience.

I kept going back to Cuba and about five years ago, I wanted to learn a lot more about the diamond story. I felt like no one knew about it. I decided to write up as much as I could about it. I kept saying, “Why haven’t people talked more about this amazing story?”

Robin had been doing a few interviews with my mom and I finally said, “Will you help me make a film about this?” People are passing on so we decided to diligently capture as many testimonials as we could.

JCK: Why did the refugees end up in Cuba?

Kreith: Cuba was one of the only counties that was allowing refugees. It was a corrupt government but at least they were letting people in—whereas, in the United States, the doors were closed. Cuba let refugees purchase visas. They were supposed to be temporary visas but they ended up staying.

Most of the refugees hoped to go to the United States. But after Pearl Harbor, once the U.S. and Cuba entered the war, there was no travel at any time.

JCK: How did the diamond trade become involved?

Kreith: Most of the refugees learned their trade in Cuba. There were some diamond experts and they not only brought as many diamonds as they could carry, but they also brought their contacts. They were able to convince the U.S. and Cuban governments to continue to import diamonds during that period. They were able to keep trade going since Antwerp was shut down.

JCK: Did the refugees assimilate to the local culture?

Robin Truesdale: It varies. Some of the people we interviewed didn’t have a lot of integration with the Cuban culture—they were so busy working in the factories all day. It depends on the family and their philosophy. Integration was not 100 percent.

JCK: Did any stay after the war?

Kreith: Some of the refugees did stay. The Cubans would have been very happy if they stayed. The refugees were very hardworking and they had this incredible business, but so many of them, their vision was to go to the United States. Some also returned to Belgium because the Belgium government tried to get them back.

If anyone had any illness or something wrong, it was impossible to get into the United States. You had to be completely healthy. So there were a couple of stories I know of people that had to stay in Cuba.

JCK: Are there any remnants of the refugees there today?

Kreith: Very few. When Castro came in many people left.

JCK: The time in Cuba seems to have been mostly positive, but there must have been some difficult stories too.

Truesdale: There was a detention camp when the refugees arrived in Havana. I think it got harder for the refugees that arrived later since they started keeping them longer.

Kreith: For most of them, the time in Cuba was quite miraculous. People kept saying that we were incredibly lucky. That was the word we kept hearing, how lucky people felt to get to Cuba.

But many of them left family behind in Europe. In many cases, family members did not survive the war. These are very difficult moments in the film, also—when family members in Cuba realized what had happened to loved ones in Europe.

JCK: What impact did this have on the diamond industry?

Kreith: Many of the people who learned their trade in Cuba went on the be quite successful in the diamond trade. They had an enormous impact on what came later. So much in Antwerp had shut down but it was really Cuba that carried on.

JCK: Did anything surprise you while making this film?

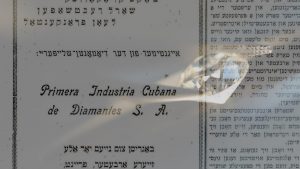

Kreith: What was amazing was the machinery that was made in Cuba. When we see the photos, all the machines were created in Cuba. This entire industry sprang up and then it disappeared. That was incredible to me. It appeared then disappeared so quickly.

JCK: What are your plans for the film?

Truesdale: We are just starting to distribute. We are having it translated into Hebrew; we will be sending it out this summer to Israel.

This is a personal story for so many people and by getting it out, we are getting together the people who shared the experience.

Kreith: It is my hope that we can show the film in Cuba. It’s a tribute to Cuba, just pointing out there was a time when Cuba offered refugees a haven at a time when so many countries shut their door.

(Images courtesy of Forgotten Jewels)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine